Informacje o artykule

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em96.1580

W wersji drukowanej czasopisma artykuł znajduje się na s. 70-81.

Pobierz artykuł w wersji PDF

Pobierz artykuł w wersji PDF

Abstract in English

Abstract in English

Jak cytować

Alam, S., & Al-Hawamdeh, B. O. S. (2022). Dynamics of integration of process drama in EFL classrooms: A holistic approach of activity based pedagogy. e-mentor, 4(96), 70-81. https://doi.org/10.15219/em96.1580

E-mentor nr 4 (96) / 2022

Spis treści artykułu

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The dynamics of drama approaches and their evolution in classroom pedagogy

- Collaboration, synthesis and group cohesion

- Aims and objectives of the study

- Research methodology, hypothesis, and procedure of data collection

- Analysis and conclusions of the study

- Findings of the study

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- References

Informacje o autorach

Dynamics of integration of process drama in EFL classrooms: A holistic approach of activity based pedagogy

Sohaib Alam, Basem Okleh Salameh Al-Hawamdeh

Abstract

Theatre/drama is an art form that conveys feelings and emotions, as well as thoughts and concerns from the history of human civilisations. Theatre and drama have been used and defined for educational purposes in many different ways. They can be effectively assimilated in language classes to achieve a communicative goal through the integration of four basic language skills (LSRW), and are a powerful tool for engaging students with content. Drama engages students in social contexts where they can think, imagine, talk, manipulate concrete materials and share their views on various social issues. This study uses a quantitative method to collect data from respondents and explores students' perspectives on the use of drama techniques for educational purposes. This paper aims to explore the main problems and challenges faced by teachers in real classroom situations. It also describes how educational drama activities can be assimilated into second-language classrooms, and highlights the strategies of role-play, visualisation and classification, as well as how they can be used in the classroom. It also aims to discuss how drama techniques can be effectively improvised and implemented in English language teaching in an EFL/ESL context.

Keywords: theatre, drama approaches, language skills, improvisation, implication, language learning, pedagogy, integration, dynamics

Introduction

As a discipline, and all over the world, language teachers face a dilemma as to which specific methodology is most likely to support intensive language learning. Globalisation and technological developments have made it much easier to reach all corners of the globe, but linguists are still searching for the ideal approach, method or technique for learning a foreign language. However, second language acquisition is a complex and difficult process in many ways. For example, students who learn English as a foreign language do not have exposure to native English on a regular basis and do not have the opportunity to use the language in everyday conversations. Even though English in India is considered a second language, and is the official language in a classroom environment, undergraduate students still have a relatively poor grasp of the language.

Communicating with other people around the world to exchange information, seek knowledge or do business is a bare necessity in today's world. To communicate with the rest of the world you need a common medium, and that medium is English. It is a bridge connecting you to the rest of the world. Gavin Bolton very rightly perpetuates that drama can be the medium of language through which human emotions, thoughts and feelings travel. Drama and theatre can be a medium whereby teaching and learning can be done more easily, with less effort, especially in an ESL context, as such students are not directly exposed to English in everyday life.

The dynamics of drama approaches and their evolution in classroom pedagogy

Educational drama a term in itself suggests that it is a process approach rather than a product. The origins of the idea of educational drama can be seen in the works of Brian Way, Gavin Bolton, Dorothy Heathcote, Peter Slade and Winifred Ward (Creative dramatics, 1930), who work in the respective fields of drama in education and theatre in education. The idea of incorporating and improvising drama and theatre techniques into classroom pedagogy dates back to around 1954, when Peter Slade wrote a book entitled Child drama (1954), followed by Brian Way's groundbreaking work Development through drama (1967), after which the concept was enriched by Bolton's Towards a theory of drama in education (1979), Bolton and Dobson's Drama in education: Learning medium or arts process (1983), and later Robinson's Exploring theatre and education (1980). The concept emerged as a teaching methodology when Cecily O'Neill published her groundbreaking works Drama Worlds: A framework for process drama (1995) and Drama structures: A practical handbook for teachers with Alan Lambert in 1982. Subsequently, a number of researchers, such as B. J. Wagner (2007a) and Shin-Mei Kao and Cecily O'Neill (1998), also contributed to the genre with rich ideas and concepts. A book by Philip Taylor and Christine D. Warner (2006) entitled Structure and spontaneity: The process drama of Cecily O'Neill is an important resource that discusses the dynamic interaction between drama theory and practice in education, process drama and many other perspectives on approaches to teaching with drama. Another key researcher, Erika Piazzoli (2010), argues that "through a combination of different drama strategies, students are able to engage in intercultural development and awareness, and in this respect process drama and drama in education positively influence students' attitudes towards a wider range of contexts and language skills" (pp. 400-401).

Theatre and drama, as a medium for teaching English, facilitate understanding of complex linguistic structures; they formulate situations through which students can grasp the concept of syntax and semantic use of language; and, above all, they address hesitation in real-life situations, developing creativity and collaboration among peers. They are a powerful and flexible framework of pedagogy that supports and extends morphological reinforcement and semantic understanding

More so, drama continually enlivens the learning of a language and transforms classroom pedagogy by introducing fictional roles and situations that meet the unpredictability of real life. Traditionally, teachers were the main source of knowledge in the classroom. They were like observers and facilitators of everything that happens in the classroom. Nowadays, classroom dynamics have changed and students are heterogeneous and multilingual. As teachers and educators, the current needs are to embrace students in order to re-imagine tomorrow. This is only possible by implementing drama methods in classroom pedagogy. With materials now more readily available at our fingertips than ever before, teachers have the opportunity to make our classrooms less teacher-centred, with the focus shifting towards student autonomy. Drama brings students and teachers together on one platform and will be the foundation of successful classrooms.

The drama approach as a teaching concept aims to make language learning easier and more meaningful for students, and can be used in ESL or EFL classrooms. Imagination is one of the key aspects of drama in education. Additionally, it is an approach to language teaching in which the teacher and students can swap roles to understand language forms and their functions. The method is flexible, student-centred and develops classroom motivation among students. In language classrooms in India, where traditional teaching methods are still in use, this teaching method offers speaking and writing practice and enhances students' skills by facilitating their imagination and experiences to enrich creativity and discovery rather than memorisation. The drama approach is a post-method idea that promotes student autonomy in the classroom. Cecily O'Neill, a renowned researcher and international authority on educational drama, describes theatre and drama as a method of exploring a problem, situation, ideas and themes through the use of improvisation, artificial roles and situations through the use of unscripted drama. It requires educators to reflect in their roles. Furthermore, Alam (2022) emphasises:

In order to develop an effective and efficient teaching strategy model, language inquiry-based activities that aim to improve productive and receptive English language learning skills are a key pragmatic strategy that can be developed and applied in foreign language classrooms. (p. 2)

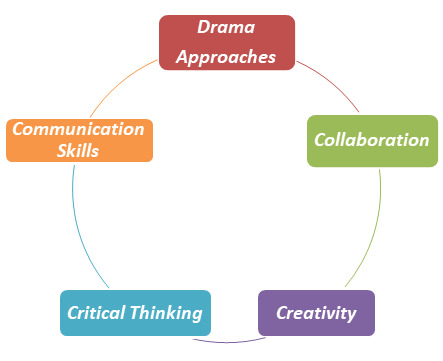

Figure 1

Drama approaches and classroom pedagogy module

Source: authors' own work

Drama approach in the classroom usually involves the whole class performing activities for which the teacher assigns roles. Students and teachers work together to create an 'invented' dramatic world in which specific real-life issues are considered and many other problems are addressed. It is the teacher's responsibility to allow for dramatic tension and complexity in the performance, as the aim is to seek pedagogical outcomes. This helps students to learn as well as think beyond their perception, and contemplate many other perspectives on the same topic through different role plays. For example, a single linguistic structure of English can have multiple interpretations that could be used in different social settings. Each form has multiple functions, and through drama students can easily understand the use of language structures. As such, creating complexity and helping students explore multiple dimensions of a topic is the idea behind the use of educational drama in classroom pedagogy.

Educational drama develops the ability to perform in 'real life' by casting students into artificial roles and situations. Betty Jane Wagner (2007b) writes:

The aim of educational drama and process drama is to create an experience through which learners can understand human interactions, emphasise the importance of other people and internalise alternative points of view. In process drama participants encounter a situation or problem, but the dialogue and gestures they create are in response to circumstances that the group imagines or improvises. (pp. 5-6)

Collaboration, synthesis and group cohesion

Collaboration, synthesis and group cohesion The CLT approach in language teaching supports techniques such as group work, pair work and think-pair-share. Drama in pedagogy initiates classroom collaboration between students for better learning outcomes. It is also considered a pedagogy model of student teaching. Cecily O'Neill and Alan Lambert (1995) emphasise:

Drama is essentially social in nature and involves contact, communication and negotiation of meaning. The group nature of it places some pressure on the participants, but also brings significant benefits. Students are trained to work individually, and to be both competitive and possessive about their achievements. Drama, on the other hand, works on the strength of the group. It draws on a common pool of experience and thus enriches the minds and feelings of the individuals in the group. The significance of drama is built from the contributions of individuals, and if this work is to develop, these contributions must be monitored, understood, accepted and responded to by the rest of the group. By group here we mean the whole class, including the teacher. (p. 13)

Drama in the classroom also teaches students how to work and succeed in a group. O'Neill and Lambert (1995) argue that:

In drama, the representation of experience that each individual offers to the group is subject to the scrutiny of the others. What is offered can be modified by others, who in turn have to modify their own contributions. The group's ability to build on the contributions of others and respond appropriately will increase with experience in this process and will be accompanied by increasing confidence in dealing with unexpected or unpredictable elements that arise. Within the safe framework of acting, individuals can see that their ideas and suggestions are accepted and used by the group. They can learn how to influence others, rationalise effective arguments, present them appropriately, and put themselves in other people's shoes. They can try out their roles and receive immediate feedback, with the group thus becoming a powerful source of creative ideas and effective criticism. (p. 13)

Figure 2

The nature of the classroom when using drama as a pedagogical strategy

Source: authors' own work.

The drama approach identifies the key role of dialogue and conversation in the classroom through the development of fictional situations and roles. It applies dialogue techniques as an adventure for students who take on the roles of others. Through role-playing, students gradually develop new perspectives and open doors through which they can learn about real language use.

Furthermore, dialogues and conversations define who we are as human beings, which is the first step to developing relationships with others in or outside the classroom. In addition, educational drama informs, excites and engages students in productive dialogue to develop language skills. It offers the opportunity to learn something new and discover other people's perspectives on different issues. It is like reading a book - you can turn any page and skip to your favourite chapter. Dialogue has the potential for immediate feedback.

Figure 3

Strategies used in real classroom pedagogy while applying drama techniques

Source: authors' own work.

Aims and objectives of the study

The aim of the study is to test the effectiveness of the drama approach and its various techniques used in classroom pedagogy, with focus on developing accuracy and fluency in learning. It also focuses on strengthening vocabulary, critical thinking, and social, cultural and personal values among students. This study seeks to identify different elements of drama approaches in EFL/ESL pedagogy that develop communicative competence among students based on the respondents' perspectives.

Research methodology, hypothesis, and procedure of data collection

The methodology carried out in this study is based on a quantitative data collection method using a researcher-developed questionnaire. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire was tested through Cronbach's alpha (0.9) and a pilot study before the actual data collection from the sample population. The sample for the study was selected by purposive sampling. The target population comprises undergraduate students studying a variety of courses and departments. The study covers 1003 undergaduate students, both male and female, studying at the Aligarh Muslim University in India. The procedure to collect data from the participants used a method in which the researcher himself visited multiple classrooms with a large number of students available. In general, the number of undergraduate students in Indian general English classes is high. The researcher obtained permission from the relevant authorities to collect data. Each class consisted of approximately 50 to 60 students, and it took about two years to collect all the data from the students. The current study is an extension of the researchers' doctoral thesis.

Ho1: The study hypothesis is that activities based on theatre and drama approaches can be used in a more interesting/motivating approach to learning than other ESL/EFL classroom pedagogy approaches.

Ho2: Drama approaches and techniques can result in improved accuracy and fluency among learners. It also improves non-verbal skills, vocabulary, critical thinking, and social, cultural and personal values in real-life situations through the use of classroom pedagogy activities.

Details of the data collection procedure are described below (Table 1). Due to the short duration of the classes, the researcher had 40 minutes with each class. In this time frame, the researcher had to discuss, introduce the concept and then divide the classes into groups of 5 or 6 depending on the size of the class. The data collection took almost two years (2017-18) to complete. This study is an extension of the researcher's doctoral thesis.

Table 1

Details of the data collection process (Aligarh Muslim University, India, 2017-18)

| Faculty | Classroom where the activities where administered | No. of students (Male and Female) | Time |

| Arts Faculty & Women's College | 12 | 435 | 35 minutes |

| Social Science | 8 | 223 | 35 minutes |

| Engineering | 4 | 95 | 35 minutes |

| Commerce | 4 | 120 | 35 minutes |

| Law | 2 | 50 | 35 minutes |

| Science | 3 | 80 | 35 minutes |

Source: authors' own work.

Sample activities

Sample activity I

Objective: To develop reading and speaking skills

Level: Undergraduate Time: 10 minutes for each group

Group: Heterogeneous Material Required: Any short story from a prescribed textbook with a length of at least 300 words.

Skills involved: Speaking, reading and comprehension

Preparation: Prepare copies of the story according to the number of students in the class and distribute it among pairs of students to read silently.

Procedure: Divide the students into pairs or groups, depending on the needs of the activity, and give everyone a copy of the story. Student A reads a randomly selected line from the story and student B is then tasked with finding the passage in the text. Once students A and B have completed the task, it is continued by other pairs and groups of students. In the meantime, the teacher should play the role of torch bearer and give clues to help students find specific lines. Ask students to choose any issue they feel comfortable with in front of the class. This will minimise students' hesitation and by performing this exercise they will improve their pronunciation. At first, it is recommended to help students feel more comfortable in performing their lines from the passage.

Sample activity II

Objective: Developing imaginative power and speaking and writing skills.

Level: Undergraduates Time: 10 minutes for each group

Group: Heterogeneous Material Required: Videos with different characters and situational dialogues.

Skills involved: Speaking and cognition

Preparation: Find and choose a video containing a discussion on any current issue that is going in the country. Erase the voice-over of the video or mute the video in order to make students imagine the discussion going on.

Procedure: Divide the class into groups of three students. Explain that they should imagine new inventions to get rid of existing problems such as sanitation, waste management, etc. Distribute one sheet each to the groups of three. The sheets contain pictures and descriptions of recent inventions to minimise social problems. If they do not answer, the teacher should suggest ideas to them. After preparation, let them present it to the class. While they present their idea, the others should carefully observe and rate the presentation on a scale of 1 to 10. One by one, after the presentation, the teacher should provide them with any necessary feedback and tell them where and how they should improve their spoken and written language.

The present study follows a dynamic methodology of learning-by-doing or a real-life representation of activities based on educational drama and can be used to teach English in an actual classroom. More than thirty questions were asked, based on a five-point Likert scale, but a few questions and their data were selected for this study. A limitation of the study is that the researcher cannot include all the data in the current study. Some items were deliberately selected and included in the present study to test and demonstrate the effectiveness of educational drama in ESL/EFL pedagogy.

The questionnaire included questions based on different aspects of educational drama, which primarily aimed to gather students' perspectives on approaches to using action-based learning in actual classroom pedagogy. The study deliberately selected questions that focused on action-based learning. A detailed analysis carried out for the study is discussed below, along with conclusions on the data collected through the questionnaire.

Analysis and conclusions of the study

The study used SPSS version 20 software to analyse the data, which was collected using a questionnaire designed by the researcher. Careful data coding and classification is performed and the percentage and cumulative percentage were calculated with the help of SPSS software. However, there were seven statements based on a five-point scale included in this study.

Figure 4

(Data based on simulation)

Source: authors' own work.

The first statement is based on a simulation (S1), with the individual statements relating to situational language use helping to improve students' accuracy and fluency, and enrich their vocabulary. Acting out dialogues in a given situation is an effective way to motivate students to develop their speaking skills.

The responses recorded show that twenty-two (22) students selected 'strongly disagree', thirty-two (32) students selected 'disagree', one-hundred-and-ninety-six (196) students selected 'neutral', four-hundred-and-ninety (490) students selected 'agree' and two-hundred-and-sixty-three (263) students selected 'strongly agree' (Figure 4).

The participants are convinced that engaging in a dialogue in a specific situation will improve their language skills. These exercises are also beneficial in improving students' pronunciation. The data collected for statement S1 provide important information about the use of dialogues as a strategy to improve language and pronunciation. Figure 4 shows us that dialogues influence the language used in social situations. Only 5.45% of students responded negatively to this statement, while 75.3% of students responded positively. Dialogues are an easy way to improvise in a language classroom to provide students with a form of verbal training.

Figure 5

(Data based on simulation)

Source: authors' own work.

The next simulation statement (S2) aims to explore the usefulness of simulation as a way of describing any situation or concept using body language. It is a problem-solving activity that helps students use language according to the situation.

The responses recorded were as follows (see Figure 5): twenty-one (21) students responded 'strongly disagree' to the statement, fifty-seven (57) students responded 'disagree' two-hundred-and-three (203) students responded 'neutral', four-hundred-and-eight (408) students responded 'agree' and three-hundred-and-fourteen (314) students responded 'strongly agree'.

As Figure 5 shows, only 7.8% of students responded negatively to this statement, while 72.2% of students responded positively. This demonstrates that simulation exercises are helpful for learning unfamiliar situations and using language structures in unscripted real-life situations. As most simulation activities are semi-structured or half-structured, it challenges students to speak and use body language gestures to describe and make their peers understand difficult life situations.

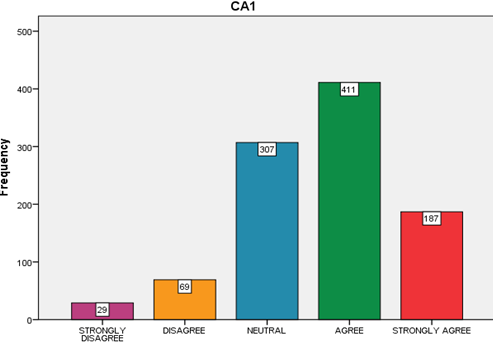

The next statements are based on cognitive abilities, which were coded for classification as CA. This statement aims to address the issue of non-verbal classroom drama activities improving students' body language. Body language is an important aspect of language learning, namely kinesiology, the study of gesture and posture.

Figure 6

(Data based on cognitive ability)

Source: authors' own work.

The recorded responses showed that (see Figure 6): twenty-nine (29) students selected 'strongly disagree', sixty-nine (69) students selected 'disagree', three-hundred-and-seven (307) students selected 'neutral', four-hundred-and-eleven (411) students selected 'agree' and one-hundred-and-eighty-seven (187) students selected 'strongly agree'. As illustrated in Figure 6, only 9.8% of students responded negatively, while 59.8% of students responded positively to this statement. However, 30.6% of students responded neutrally to the question about the contribution of non-verbal actions in improving body language. The data clearly shows that students' non-verbal skills are improving, and they believe that by using these activities they will enhance their productive language skills. However, many respondents were unable to determine their progress because these skills are not visible when using them in a real-life situation.

Another cognitive ability statement (CA2) seeks to ask how active and engaged students feel when drama and theatre activities are used in the classroom. The drama approach in education gives autonomy to students in the classroom and engages them in the learning process.

Figure 7

(Data based on cognitive ability)

Source: authors' own work.

The recorded responses after data classification showed that: thirty-seven students answered 'strongly disagree', fifty-one students answered 'disagree', two-hundred-and-forty-one (241) students answered 'neutral', five-hundred-and-fourteen (514) students answered 'agree', and one-hundred-and-sixty (160) students answered 'strongly agree'. Figure 7 shows that only 8.8% of students responded negatively, while 67.4% of students responded positively to this statement. The participants' responses show that students who are involved in classroom pedagogy using drama activities have to move from one place to another and use language spontaneously with their partners. Thus, the students accepted that they feel more involved when their teacher uses drama activities in classroom pedagogy.

Another finding of cognitive ability (CA3) relates to students' choices of whether or not to play vocabulary development games on different platforms such as newspapers, mobile phones or the Internet. Nowadays, the Internet is full of sites promoting online learning through various language exercises, lessons and activities.

Figure 8

(Data based on cognitive ability)

Source: authors' own work.

The recorded responses were as follows (see Figure 8): twenty-nine (29) students selected 'strongly disagree', sixty-five (65) students selected 'disagree', two-hundred-and-twenty-four (224) students selected 'neutral', three-hundred-and-seventy-six (376) students selected 'agree', and three-hundred-and-nine (309) students selected 'strongly agree'.

In addition, mobile apps are an easy way to acquire language skills and are easily accessible for everyone. The internet is easily accessible to students, and they can make good use of it if they use it in a positive way. Online dictionaries and newspapers (offline and online) are authentic sources to develop vocabulary. Figure 8 shows that only 9.4% of students responded negatively, while 68.5% of students responded positively to this statement.

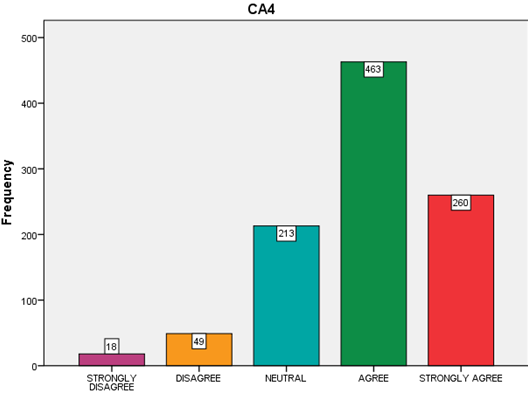

A further statement based on cognitive ability (CA4) inquires about the role of drama-based activities in developing students' communicative ability.

Figure 9

(Data based on cognitive ability)

Source: authors' own work.

The recorded responses after classification (see Figure 9) showed that: eighteen (18) students selected 'strongly disagree', forty-nine (49) students selected 'disagree', two-hundred-and-thirteen (213) students selected 'neutral', four-hundred-and-sixty-three (463) students selected 'agree', and two-hundred-and-sixty students selected 'strongly agree'. Figure 9 shows that only 6.7 percent of students responded negatively, while 72.3 percent of students responded positively to this statement, meaning that a large number of students strongly believe that drama activities enhance their communication skills. This is because they are engaging and allow students to discuss and share their thoughts, feelings and emotions in a healthy classroom environment.

The next statement in this segment (CA5) asks about developing critical thinking among learners using dialogues as an exercise. Dialogues are an effective strategy in second-language classrooms and a holistic process that develops all four language skills.

The recorded responses after classification (see Figure 10) show that: seventeen (17) students selected 'strongly disagree', fifty (50) students selected 'disagree', two-hundred-and-eighteen (218) students selected 'neutral', four-hundred-and-sixty-eight (468) students selected 'agree', and two-hundred-and-fifty (250) students selected 'strongly agree'. As Figure 10 shows, only 6.7% of students responded negatively, while 71.8% of students responded positively to this statement. Dialogues force students to act and speak while acting out a hypothetical situation or personality. They find it an effective way to improve their language skills and cognitive abilities.

Figure 10

(Data based on cognitive ability)

Source: authors' own work.

The next statement is designed to address the development of cultural, personal and social values among students through drama activities. The recorded responses (see Figure 11) were: seventeen (17) students selected 'strongly disagree', forty-six (46) students selected 'disagree', two-hundred-and-twenty-three (223) students selected 'neutral', four-hundred-and-sixty-seven (467) students selected 'agree', and two-hundred-and-fifty (250) students selected 'strongly agree'. As shown in Figure 11, only 6.3% of students responded negatively and 71.7% of students responded positively to this statement. The data reveals that drama improves students' social, personal and cultural values.

Drama activities allow students to share and interact while acting or role-playing in the classroom, and through this strategy they develop and learn social, personal and cultural values by sharing their views on different ideas and topics, and receiving feedback.

Figure 11

(Data based on cognitive ability)

Source: authors' own work.

The final cognitive ability statement (CA7) explores the development of understanding and concentration through the use of various drama exercises. The responses recorded for this statement after classification of the data (see Figure 12) were as follows: eighteen (18) students selected 'strongly disagree', forty (40) students selected 'disagree', two-hundred-and-seventeen (217) students selected 'neutral', four-hundred-and-fifty (450) students selected 'agree', and two-hundred-and-seventy-eight (278) students selected 'strongly agree'. The data reveals that drama exercises improve concentration, as students have to listen to their peers while performing various language skills as part of the classroom pedagogy, and they need to listen and respond to their peers in order to actively participate in the classes.

Figure 12

(Data based on cognitive ability)

Source: authors' own work.

Findings of the study

The findings of this study are a direct reflection of the hypothesis formulated and discussed above. The findings are:

- Students are inconsistent with their oral skills when asked to participate in class. This indicates a lack of an autonomous classroom environment, providing a need to introduce activities that are spontaneous and aim to improve students' creativity. Activities are needed that are spontaneous and aim to improve students' creativity, enabling them to be active learners. This finding is directly related to Ho1, where simulation-based activities were used to collect data. In this respect, structured and unstructured activities based on role-play and enactment were also used.

- The findings suggest that students have difficulty expressing their opinions, feelings and lack conversational skills. It also reveals that there should be a diagnostic test of students' oral and written skills to assess communicative competence, so that future action could be taken to increase language proficiency. This supports Ho2 in that drama activities develop students' communicative skills.

- It was noticed that the curriculum does not promote students' kinesthetic skills, resulting in hesitant and reluctant body language. It was also found that the curriculum does not include elements that aim to reinforce suprasegmental features of language. Students show a lack of competence when it comes to the delivery of non-verbal language skills, as the curriculum does not give room for the improvement or development of non-verbal language skills. The findings support Ho2 in that drama activities promote critical thinking and non-verbal language skills in real-life situations.

- In order to strengthen the four language skills and two aspects of the English language (listening, speaking, reading, writing, vocabulary and grammar), the curriculum designer and material developer should propose an alternative and holistic process, covering all components of the language. The syllabus and curriculum should place more emphasis on improving speaking and pronunciation skills, as students are not able or do not have the opportunity to use English in everyday life.

- It was also observed that students do not have the chance to express themselves in the classroom due to the existing practice of applying lecture-based teaching. An interactive classroom should be encouraged, as it helps to reduce students' hesitation and enables them to learn language expression. Research findings reveal that drama activities provide a more engaging and less authoritarian classroom. It also promotes communicative language teaching.

Conclusions and discussions of the study

The findings of this study are discussed below. Each item was carefully analysed and discussions were carefully conducted after analysing the responses recorded from the students.

- Since the analysis of students' needs is an important aspect of ELT, it should be introduced into the curriculum through systematic regulation. It was found that the existing curriculum does not promote and develop English language competence when it comes to delivering it in real-life situations, which is among the goals of students choosing English.

- In addition, the syllabus is not capable of fulfilling the requirement to improve speaking and writing skills in English. It was observed that there is no room in the syllabus and curriculum for authentic materials that can be used by students and teachers to work on oral skills. The materials provided in the syllabus are not suitable for developing the students' performance.

- The syllabus and materials are not based on ABCD (audience, behaviour, content, and degree), resulting in inconsistencies in classroom procedures. The syllabus and materials should be designed according to the level and knowledge of the students, which should be achieved through the implementation of pre-behaviour (EB) assessment of students.

- Best practices are not introduced through a professional development programme focusing on developing knowledge of content, methods and instructional resources to encourage professional development of teachers to update and expose them to the use of theatre and drama approaches in language classrooms.

- Implementing a reflective practice method in the classroom to enhance the teaching-learning process is also required. It was found that educators are reluctant to use the activity-based method or reflective practice due to the heterogeneous nature of the classroom. The reason for this is the burden of having to complete the syllabus in a set time.

Conclusion

In classroom pedagogy the swing in the communicative approach to language teaching has shifted towards a student-centred classroom, with the role of the teacher being to act as a facilitator and torchbearer, although the teacher as a person can in no way be replaced. A counter-narrative is now available in the form of distance learning, but the teacher is still an essential phenomenon in classroom teaching. Furthermore, drama and theatre as a pedagogical medium are successful because of their potential and the hard work and dedication that the teacher brings to the classroom. As Maley and Duff (2013) put it, drama is not a dead issue, it is like a living organism - it was, is and will continue to be. The teacher's motivation and contribution is equally important, as they know their students and can plan their activities and lessons, or the pace of the class, according to the students' level, understanding and background knowledge. Drama as a teaching methodology recommends the use of self-designed materials and activities in the classroom to explore the power of the method in teaching English. As Alam et al. (2021) point out, 'the approach is able to assimilate all four language skills and can be an effective and efficient pedagogical strategy' (p. 271). Studies by Alam et al. (2020), Alam et al. (2022), Al-hawamdeh and Alam (2022) are beneficial because they discuss some exemplary activities in their research. Either the teacher needs to come up with an activity according to the nature of the class or make some changes accordingly. The articles also discuss the importance of blended learning, and the challenges and problems teachers face in real classroom pedagogy. Finally, success is entirely dependent on teachers' involvement and participation in classroom procedures. Heathcote's idea of the role of the teacher is very relevant in this perspective.

Acknowledgement

This project was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University under project no. 2021/02/18222, Al Kharj, Saudi Arabia.

References

- Alam S. (2022). Imagine, integrate, and incorporate: English language and its pedagogical implications in EFL classrooms. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v14n2.10

- Alam, S., Al-Hawamdeh, B. O. S., Ghani, M. U., & Keezhatta, M. S. (2021). Strategy of improvising drama in education: praxis of pedagogy in EFL/ESL context. The AsianESP Journal, 23-41. https://www.asian-esp-journal.com/esp-17-4-2-2021/

- Alam, S., Faraj Albozeidi, H., Okleh Salameh Al-Hawamdeh, B., & Ahmad, F. (2022). Practice and principle of blended learning in ESL/EFL pedagogy: strategies,techniques and challenges. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 17(11), 225-241. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v17i11.29901

- Alam, S, Karim, M. R., & Ahmad, F. (2020). Process drama as a method of pedagogy inESL classrooms: articulating the inarticulate. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 11(1), 255-272. https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs2020.1.255.272

- Al-hawamdeh, B. O. S., & Alam, S. (2022). Praxis and effectiveness of pedagogy during pandemic: an investigation of learners' perspective. Education Research International. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3671478

- Bolton, G. M. (1979). Towards a theory of drama in education. Longman.

- Bolton, G. M., & Dobson, W. (1983). Drama in education, learning medium or arts process? Published by NATD in association with the Longman Group.

- Kao, S.-M., & O'Neill, C. (1998). Words into worlds: learning a second language through process drama. Praeger.

- Maley, A., & Duff, A. (2013). Drama techniques in language learning. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368828401500211

- O'Neill, C. (1995). Drama worlds: A framework for process drama. Heinemann.

- O'Neill, C., & Lambert, A. (1995). Drama structures: A practical handbook for teachers. Heinemann.

- Piazzoli E. (2010). Process drama and intercultural language learning: an experience of contemporary Italy. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 15(3), 385-402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2010.495272

- Robinson, K. (1980). Exploring theatre and education. Heinemann.

- Slade, P. (1954). Child drama. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Taylor P., & Warner C. D. (2006). Structure and spontaneity: the process drama of CecilyO'Neill. Trentham Books.

- Wagner, B. J. (2007a). Dorothy Heathcote: Drama as a learning medium. Heinemann.

- Wagner, B. J. (2007b). Educational drama and language arts: what research shows. Heinemann.

- Ward, W. (1930). Creative dramatics. Appleton and Company.

- Way, B. (1967). Development through Drama. Humanities Press.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9972-9357

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9972-9357