Informacje o artykule

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em99.1610

W wersji drukowanej czasopisma artykuł znajduje się na s. 56-68.

Abstract in English

Abstract in English

Jak cytować

Młynkowiak-Stawarz, A. (2023). Do Polish tourists want wellbeing tourism? Preferences for wellbeing tourism versus the psychological wellbeing of individuals. e-mentor, 2(99), 56-68. https://doi.org/10.15219/em99.1610

E-mentor nr 2 (99) / 2023

Spis treści artykułu

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The theory of psychological wellbeing in tourist behaviour research

- Review of the concept of wellbeing tourism in literature

- Methodology

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusions

- Limitations

- References

Informacje o autorze

Do Polish tourists want wellbeing tourism? Preferences for wellbeing tourism versus the psychological wellbeing of individuals

Anna Młynkowiak-Stawarz

Abstract

This paper is part of a study on the impact of tourism experiences on the psychological wellbeing of individuals. Integrating the approach of positive psychology and research on tourists’ behaviour within the field of marketing, Caroll Ryff's concept of psychological wellbeing and the concept of wellbeing tourism were used for this purpose. The aim of the research was to investigate differences in the level of perceived psychological wellbeing by tourists preferring different types of wellbeing tourism, and the article presents theoretical and practical premises for defining wellbeing tourism. Wellbeing tourism can be defined as a specific type of tourism based on six pillars that ensure a sustainable approach to travel and leisure - simultaneous care for the body, soul, and mind of the tourist, as well as the environment, society, and economy of the destination area. Through analysis of variance, it was found that these differences are significant for those preferring natural and cultural wellbeing tourism, and they are also influenced by the perception of one's financial situation. Applying the results of the study will enable tourism enterprises to design an offer for tourists that will increase their sense of psychological wellbeing.

Keywords: wellbeing tourism, psychological wellbeing, preferences of tourists, nature tourism, cultural tourism

Introduction

The global health crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the climate crisis and the international military crisis caused by the war in Ukraine all have a huge impact not only on the global economy, but also on the psychological wellbeing of individuals (Bolotnikova et al., 2023; Chudzicka-Czupała et al., 2023; Koole & Rothermund, 2022; Ng & Kang, 2022; Pilar Matud et al., 2022). The conducted research indicates that external events that have affected entire communities in recent years significantly impact an individual's sense of wellbeing. It is a truism to say that everyone wants to experience the highest possible level of wellbeing and thus be happy, but research on the psychological wellbeing of individuals, considered as one of the indicators of happiness, demonstrates that nowadays, during different periods related to global health and security crises, people show a general deterioration of perceived wellbeing (Bassi et al., 2022; Daly et al., 2020; Koole & Rothermund, 2022; Lewis et al., 2022, p. 28; Vanaken et al., 2022). This condition influences the decisions that individuals make in relation to many aspects of their lives, including choices related to the fulfilment of tourism needs (Buckley, 2022; lo & Peralta, 2022).

Despite the recovery in tourism-related travel observed in 2022, tourists still travel less than they did it prior to the pandemic crisis (UNWTO, 2022). Buckly notes that the simple relationship regarding the impact of psychological wellbeing, as perceived by individuals, on their tourism behaviour aptly captures the need to link research on individuals' psychological wellbeing with their tourism preferences. Decisions related to spending money on travel is linked to the expectation of experiencing pleasure. Pleasure is linked to wellbeing, and wellbeing has an impact on various elements of a person's health, which in turn has significant economic value (Buckley, 2022). In addition, the preservation of psychological wellbeing is one of the motives for undertaking tourism activities during a crisis period (Aebli et al., 2022).

Due to the co-occurrence of global pandemic, military, economic and climate crises, individuals are changing their behaviour and preferences in the field of tourism (Bęben et al., 2021; Hannan et al., 2021), which implies the need for continuous research on these issues. Moreover, research linking issues of tourism and psychological wellbeing leads to the development of different types of psychological therapies used to improve the mental health of individuals, as well as opportunities for the tourism industry to create new offers, e.g. in the area of outdoor tourism (Buckley, 2019) and nature tourism (Buckley, 2020; Lück & Aquino, 2021).

The tourism industry, especially with regard to wellbeing tourism, is trying to meet the expectations of individuals related not only to interesting and enjoyable leisure activities, but also to the improvement of their overall psychological wellbeing. The study carried out focuses on finding an answer to the question "Is there a relationship between the sense of psychological wellbeing experienced by individuals and their preference for choosing a wellbeing tourism destination?", and thus fits into the stream of research related to non-economic areas affected by tourism development (Berbekova & Uysal, 2021).

In exploring the issue of the relationship between the overall psychological wellbeing of individuals and preferences for choosing wellbeing tourism, a research question was formulated:

Between which groups that preferring a certain type of wellbeing tourism are there differences related to the average level of mental wellbeing?

Interest in this issue requires us to identify what contemporary wellbeing tourism is and how the psychological wellbeing of individuals can be defined and studied. As Smith and Diekmann note, the term wellbeing is present in all areas of the social sciences, including philosophy, sociology, psychology, management and quality sciences (Smith & Diekmann, 2017), to name just the most popular ones. When typing this term into scientific and popular search engines we come up with thousands of texts, so a comprehensive view on wellbeing, therefore, requires addressing its various aspects. This paper focuses on the concept of the eudaimonistic, psychological wellbeing of individuals, as well as the types and kinds of wellbeing tourism.

To present the concept of wellbeing tourism, inter alia, the findings of a project titled 'Wellbeing Tourism in the South Baltic Region - Guidelines for good practices & Promotion' were used. The project was financially supported by the Interreg South Baltic Programme 2014-2020 with co-financing by project partners - Linnaeus University (project leader - Sweden), EUCC Baltic Office (Lithuania), Klaipeda State University of Applied Sciences, Agencja Rozwoju Pomorza S.A. (Poland), Tourism Association 'Vodelparkregion Recknitztal' (Germany), Energy Agency for Southeast Sweden Ltd (Sweden), County Administrative Board of Kalmar (Sweden), Professor Bruno Synak Scientific Institute (Poland), and Danish Tourism Innovation (Denmark). In turn, the Polish adaptation of an abbreviated version of the Caroll Ryff wellbeing questionnaire (Karaś & Cieciuch, 2017) was used to examine individuals' psychological wellbeing.

The study was conducted among Polish respondents, taking into account the situation of the Polish society, which, due to geographical reasons, is more exposed to the wide-ranging effects of the war in Ukraine. Furthermore, as previous studies have indicated, respondents from Poland also showed less acceptance of pandemic restrictions and more negative attitudes towards them (Bęben et al., 2021). The questionnaire survey was conducted in October/November 2022 among the participants of the research panel, with respondents invited for testing based on quota selection to reflect the population of adults in Poland in terms of age, gender and place of residence. In addition to this, a filter question on the use of paid tourist accommodation in the last year was used, as the aim of the survey was to test the relationship between the general psychological wellbeing of individuals and the wellbeing tourism preferences of those active in tourism. The survey was conducted using the CAWI method on 600 respondents. The UNIANOVA one-way procedure for analysis of variance was used to answer the research questions.

The theory of psychological wellbeing in tourist behaviour research

A multidimensional model of psychological wellbeing was proposed by Caroll Ryff (1989) already in the 1980s, when she developed an instrument to measure the psychological wellbeing of individuals, the Psychological Well-Being Scale, which consists of 84 statements distinguishing six dimensions of wellbeing: coping, positive relationships, autonomy, personal development, self-acceptance and life purpose. To date, it has been translated into more than 35 languages and its reliability and validity have been confirmed by some 750 studies (Kállay & Rus, 2014; Ryff, 2013; 2017).

Ryff's concept was based on the classic definition of mental health proposed by Maria Jahoda (1958), according to which it is complete physical, mental and social wellbeing, and it is consistent with the assumptions of positive psychology, integrating the good life, gratification and developmental character traits (Seligman, 2005). It also draws inspiration from the philosophical tradition of Aristotle, according to which happiness is defined as eudaimonia (Ryff, 2017), the realisation of an individual's potential, in contrast to the hedonistic context of wellbeing, which sees happiness as experiencing pleasure and satisfaction. In the context of psychological wellbeing research, the hedonistic approach is present as a measurement of subjective wellbeing (Diener, 2000).

Mental wellbeing influences various aspects of individuals' functioning (Manchiraju, 2020; Vázquez et al., 2009), and research on this issue has found, among other things, that maintaining a stable and reasonably high level of psychological wellbeing, and thus remaining engaged in various developmental activities and human connections, is associated with better somatic wellbeing and a less frequent occurrence of symptoms of chronic conditions (Heszen-Cielińska & Sęk, 2020). However, it is difficult to unequivocally say which dimension of wellbeing, hedonistic or eudaimonistic (Ryan & Deci, 2001), has a greater impact on an individual's positive functioning, especially in the context of a variety of tourism experiences, which themselves can be considered as more or less hedonistic or eudaimonistic (Voigt et al., 2010). The papers of Keyes et al. (2002) opened discussions on a holistic model of human wellbeing considering its three aspects - emotional (hedonistic), psychological and social (eudaimonistic), and have served as a basis for the design of educational and therapeutic interventions that promote individual wellbeing (Heszen-Cielińska & Sęk, 2020), also taking into account life satisfaction, positive affect, subjective physical health, absence of depression, anxiety and stress (Bhullar et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2015).

McMahan and Estes (2011), using regression analysis, developed a model in which it was the eudaimonistic approach to wellbeing that had a relatively greater impact on an individual's overall positive psychological functioning than the hedonistic one. Eudaimonistic wellbeing is also positively correlated with the realisation of activities that require challenges, skills, and are linked to self-realisation, effort and participants' interests (Waterman et al., 2008), which may characterise, among other things, tourism activities, for which the motives for undertaking them are, for example, self-realisation or the deepening of interests.

Given that individuals' tourism activities are among the behaviours that shape their perceptions of quality of life (Dolnicar et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2015; Li et al., 2022), which is relevant to a holistic view of individuals' wellbeing (Uysal et al., 2016), psychological wellbeing has also attracted the attention of tourism researchers as part of this construct (Zins & Ponocny, 2022). In research on the impact of tourism experiences on tourists' psychological wellbeing, the reference to hedonistic and eudaimonistic experiences related to different aspects of travel (Fakfare et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2021) and activities undertaken (Bosnjak et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2018) is particularly noteworthy. However, the significance of the relationships that occur between the different dimensions of psychological wellbeing, quality of life, personal development and the role of tourism experiences in an individual's life is still not clearly defined (Filep et al., 2022). Joseph Sirgy (2019) proposes a number of theories and concepts in the context of which the study of the relationship between an individual's psychological wellbeing and their tourism experience may yield results relevant to the design of appropriate tourism offers that affect not only a customer's short-term experience but also their long-term wellbeing, especially considering tourism experiences of a eudaimonistic nature (Smith & Diekmann, 2017). A summary of concepts and theories related to psychological wellbeing is presented in the table below.

Table 1

Application of theories related to psychological wellbeing in research on tourists

| Theory related to psychological wellbeing | Research | Issues related to tourism |

| Self-determination Theory | Cini et al., 2013; Ng et al., 2012; Ntoumanis et al., 2020 |

|

| The self-congruity Theory model in travel and tourism | Chon & Olsen, 1991; Sirgy et al., 2018 |

|

| Self-expressiveness Theory | Bosnjak et al., 2016 |

|

| The bottom-up spillover theory of life satisfaction | Luo et al., 2018; Neal et al., 2007 |

|

| Theory of leisure wellbeing | Lee et al., 2018 |

|

| Goal Theory | Kruger et al., 2015 |

|

| Need Hierarchy Theory | Lee et al., 2014 |

|

| Broaden-and-build Theory | Kim et al., 2016 |

|

Source: own study based on "Promoting quality-of-life and well-being research in hospitality and tourism", M. J. Sirgy, 2019, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(1), 1-13 (https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1526757); Tourist health, safety and wellbeing in the new normal (pp. 221-242), J. Wilks, D. Pendergast, P. A. Leggat, & D., Morgan (Eds.), 2021, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5415-2_9.

The examples in the table above show that research on the relationship between an individual's tourism experiences and their holistic wellbeing is firmly grounded in psychological theories and produces results that can contribute to improving the quality of different types of tourism services. They also show consumer/tourist behaviour and decisions in a broader context.

Review of the concept of wellbeing tourism in literature

With increased public interest in the topic of wellbeing, including mental wellbeing as well as its role in the holistic concept of health, there has been increased interest in the implementation of this concept in universally understood tourism activities, which has entailed increased interest from tourism researchers. Smith and Diekmann (2017) developed the Model of Integrative Wellbeing Tourism Experience, which includes pleasure and hedonism (i.e. having fun), rest and relaxation, altruistic activities and sustainability (e.g. being environmentally friendly of benefiting local communities) and meaningful experiences (e.g. education, self-development or self-fulfilment). This model is also referred to by Pope (2018) when describing the relationship between wellbeing, sustainable tourism and tourists' behaviour.

Taking into account the duration and type of tourism experience, Smith and Diekmann distinguished four areas of wellbeing in tourism. In the short-term, the level of subjective hedonistic wellbeing is influenced by tourism experiences built, for example, while relaxing on the beach, at the seaside or while attending various events, such as stag or hen parties. Medium-term effects on levels of hedonistic and eudaimonistic wellbeing are influenced by, for example, a combination of cultural tourism and participation in more hedonistic experiences, e.g. at night parties, or a combination of volunteer tourism and relaxation on the beach. Long-term effects on the level of eudaimonistic wellbeing come from tourism experiences that lead to existential authenticity, e.g. volunteer tourism, retreat tourism, spiritual pilgrimage. In contrast, permanent and optimal effects on the level of wellbeing, maximising quality of life and achieving authentic happiness are, according to the researchers, influenced by tourism experiences that are based on a sustainable, ecological and ethical approach to tourism. Smith and Diekmann's concept is a model aimed at better understanding wellbeing tourism.

This approach is also the foundation of 'The six pillars wellbeing tourism concept' (Lindell et al., 2021), to the development of which the project Wellbeing Tourism in the South Baltic Region - Guidelines for good practices & Promotion (SB WELL) contributed. Wellbeing tourism within this concept is based on six foundations - Soul, Society, Body, Environment, Mind and Economy. The authors also formulated a definition of wellbeing tourism, on which this study, among others, is based, defining it as a specific type of tourism intended to promote and maintain positive health of the body, mind and soul, composed of products and services drawn upon a sustainable interaction with the surrounding environment and community (Lindell et al., 2021), a definition that has become the basis for understanding wellbeing tourism in the conducted study. As part of the soulful foundation of wellbeing tourism, the tourism offers focuses on building an experience of beauty, joy, attentiveness and emotional balance. The mindful aspect relates to shaping an offer geared towards relaxation and tranquillity, but also creativity and creative activities. Bodily wellbeing is related to tourism focused on nourishing one's body, movement and relaxation, and the economic dimension is based on operating principles that also benefit the hosts, and is related to fair dealing, supporting the local community, and sustainable economic principles. Also the societal dimension refers to the local community, especially the principles of equal treatment, building positive relationships and cooperation. The environmental dimension refers to caring for the environment, striving for decarbonisation and eliminating waste in tourism activities (Lindell et al., 2022). According to the quoted definition of wellbeing tourism, this type of tourist can be considered as someone who, when making a travel decision, is guided by established indicators of wellbeing related to the destination, activities undertaken, and the impact of the journey on oneself and the environment.

The wellbeing tourism experience can take many forms. Initially, research on wellbeing tourism focused on specific tourism activities (Hartwell et al., 2018), wellness tourism (Kessler et al., 2020), health tourism and natural tourism (Farkic et al., 2021; Lück & Aquino, 2021; Willis, 2015). Among the main preferences of wellness tourists are physical activities and exercise, food experiences, sensations of the elements, sensations of the elements, peace and relaxation and togetherness (Lück & Aquino, 2021).

However, when considering the issue of wellbeing in the broader tourism context, it can be considered to concern the shaping of a tourism environment and experience, providing physical and psychological benefits, both for tourists and host communities, with sustainability in the operation of tourism destinations, and is based on its eudaimonistic dimension, which is expressed in the holistic construction of wellbeing. Within the different kinds of wellbeing tourism, seven basic types can be distinguished, with different tourism offers based on the above six dimensions (Lindell et al., 2022) and focusing on a specific activity. These include original and luxurious places, places focused on spiritual development, on taking care of physical health and the body, on discovering and enjoying nature or cultural goods, on outdoor activities and places targeting ecologically-oriented tourists.

Methodology

Research model and hypotheses

The model of the study is most clearly expressed by the metaphor of a funnel (Figure 1), in which different areas that influence mental wellbeing, being a complex construct, come together. To answer the research questions related to the differences between tourists declaring different levels of mental wellbeing and preferring a specific type of wellbeing tourism, the UNIANOVA one-way procedure for analysis of variance was used. The explanatory variable was eudaimonistic psychological wellbeing, defined using a shortened version of the C. Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale, while the other explanatory variables were wellbeing tourism preferences, measured separately on seven dimensions, and demographic variables: gender, age, place of residence, education and perception of one's own financial situation. The analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS software.

Figure 1

The concept of research on the mental wellbeing of tourists

Source: author's own work.

The effects of these variables on wellbeing are generally minor, but together they are of considerable importance, contributing to shaping wellbeing. To examine the results using analysis of variance, the following research hypotheses were formulated:

H1: The level of demonstrated psychological wellbeing of tourists varies according to their stated preferences in the area of wellbeing tourism.

H1a: The level of demonstrated psychological wellbeing of tourists varies according to gender.

H1b: The level of demonstrated psychological wellbeing of tourists varies according to age.

H1c: The level of demonstrated psychological wellbeing of tourists varies according to the place of residence.

H1d: The level of demonstrated psychological wellbeing of tourists varies according to the level of educational.

H1e: The level of demonstrated psychological wellbeing of tourists varies according to the perception of one's own financial situation.

The hypotheses formulated are alternatives to the hypotheses in the analysis of variance, which state that there are no differences in the study groups due to the mentioned factors.

Data collection

Responses to the survey questionnaire were collected in October/November 2022 using the CAWI method, with respondents recruited on the poznaj.to research panel owned by the PBS Research Agency. Only respondents who declared that they had taken part in a paid tourism trip in the year preceding the survey qualified. Respondents were asked three filter questions about their different activities and payments to avoid suggestive answers. A non-random quota selection method was used to select respondents, taking into account their gender, age and place of residence in Poland in 2021 (GUS, n.d.). The demographic structure (by gender) of the study group is presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Demographic structure of the study group

| Question | Women | Men | Total | ||||

| Age | 18-29 | 74 | 22.8% | 50 | 18.1% | 124 | 20.7% |

| 30-39 | 98 | 30.2% | 97 | 35.1% | 195 | 32.5% | |

| 40-49 | 70 | 21.6% | 63 | 22.8% | 133 | 22.2% | |

| 50-59 | 46 | 14.2% | 45 | 16.3% | 91 | 15.2% | |

| 60-69 | 33 | 10.2% | 17 | 6.2% | 50 | 8.3% | |

| >70 | 3 | 0.9% | 4 | 1.4% | 7 | 1.2% | |

| Total | 324 | 54% | 276 | 46% | 600 | 100% | |

| Place of residence | Village | 121 | 37.3% | 99 | 35.9% | 220 | 36.7% |

| City with up to 100,000 inhabitants | 94 | 29.0% | 76 | 27.5% | 170 | 28.3% | |

| City with more than 100,000 inhabitants | 109 | 33.6% | 101 | 36.6% | 210 | 35.0% | |

| Education | Primary and vocational | 9 | 2.8% | 7 | 2.5% | 16 | 2.7% |

| Secondary | 194 | 59.9% | 178 | 64.5% | 372 | 62.0% | |

| Higher | 121 | 37.3% | 91 | 33.0% | 212 | 35.3% | |

Source: author's own work.

There were slightly more women among the respondents, and the largest age group consisted of those aged 30-39 years. The largest proportion of respondents lived in medium cities with up to 100,000 inhabitants and had secondary education. In addition, respondents were also asked to provide an opinion on their own material situation, characterised by four different statements. The percentage distribution of responses to this question is shown in the table below.

Table 3

Distribution of respondents by perception of their own financial situation

| Self-perception of financial situation | % of answers |

| I can afford everything without making special sacrifices. | 22.67% |

| I live frugally and thus have enough money for everything. | 49.67% |

| I live very frugally in order to have money for more significant purchases. | 21.17% |

| I do not have enough money for all my basic needs. | 6.50% |

| Total | 100% |

Source: author's own work.

Respondents most often selected the answer indicating that they live frugally in order to have enough money for everything they need, while the least frequently chosen statement was that they did not have enough money for all their basic needs. Women assessed their material situation worse than men. Among the residents of cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants, the most frequent answer was that there is not enough money for all their basic needs. Those from the age groups 18-29 and 30-39 and with higher education rated their material situation the highest.

Given the nature of tourism activity, which requires involvement and often entails social interactions, as well as the long-term impact of eudaimonistic tourism activity on wellbeing, in order to study psychological wellbeing a questionnaire claiming its origin in eudaimonistic concepts was chosen. Due to the scope of the study we used the Polish adaptation of C. Ryff's Psychological Well-Being Scale, prepared by Karaś and Cieciuch in 2014. An abbreviated, 18-item version of the questionnaire was also validated to explore the general sense of wellbeing, without considering its 6 dimensions in detail, and this version was used in the current study. Respondents were asked to comment on the statements quoted, selecting answers from a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ('strongly disagree') to 6 ('strongly agree'). The overall score was calculated using a method counting the average of all questions, with eight questions considered after inverting the scale. To check the reliability of the questions selected to create the questionnaire, we used the internal consistency coefficient Cronbach's alpha. As in the Polish adaptation of the questionnaire, the coefficient obtained was quite high, at 0.815, indicating a satisfactory reliability of the tool used. All scale items also showed satisfactory reliability of approximately 0.80.

To investigate tourists' preferences regarding wellbeing tourism, we used a breakdown into seven different segments distinguished in this area, developed within the Wellbeing Tourism in the South Baltic Region - Guidelines for good practices & Promotion project. We selected a question consisting of seven descriptions, characterising the chosen wellbeing tourism destinations, to determine tourists' preferences related to a specific type of wellbeing tourism. Respondents were asked how likely it was, if their friends unexpectedly won a voucher for a 7-day holiday, that they would encourage them to choose a specific type of wellbeing tourism. Responses were given on a non-metric 10-item scale, with the question formulated based on the principles of the Net Promoter Score (NPS) (Baehre et al., 2022). Framing the question in this way enabled the elimination of the influence of season and available financial resources on a respondent's preferences. The Cronbach's ? reliability coefficient for this part of the questionnaire was also satisfactory, at 0.84. By using a 10-item scale, it was possible to operationalise the variables through the declared level of intention to recommend a particular type of wellbeing tourism destination (Beahre et al., 2022). The respondents were divided into three groups, as shown in Table 4. Those who answered from 0 to 6 were considered to disregard the place in question when recommending it, while those who answered 7 to 8 were identified as expressing a neutral stance towards a particular type of wellbeing tourism. Only those who answered 9 to 10 were identified as preferring a particular type of wellbeing holiday.

Table 4

Breakdown of survey participants by their preference for a particular destination typical for a particular type of wellbeing tourism

| Wellbeing tourism | Description of the destination | Disregarding tourists | Neutral tourists | Preferring tourists |

| Luxury | An original place with a natural balance, where you can pamper your senses and enjoy the benefits of local culture at the same time. | 17.2% | 27.7% | 55.2% |

| Nature | An interesting place to experience something new and unexpected while exploring the local countryside using the opportunities available. | 15.0% | 26.0% | 59.0% |

| Health | A safe place where you can take care of your health thanks to professionals. | 22.2% | 28.7% | 49.2% |

| Outdoor | A naturally challenging place to prove yourself, pursue your passions and meet like-minded people. | 27.3% | 28.7% | 44.0% |

| Harmonic | A soulful place to slow down, disconnect from an unhealthy lifestyle, and find peace and harmony. | 41.8% | 22.5% | 35.7% |

| Cultural | A culturally interesting place to focus, read a book, observe the beauty of local nature or monuments. | 19.7% | 30.2% | 50.2% |

| Ecological | A place to travel to while maintaining the principles of sustainable living and respect for local culture. | 21.3% | 33.5% | 45.2% |

Source: author's own work.

To simplify the description, a separate name was given for each preference, as shown in the table above. The largest proportion of respondents were willing to recommend nature and cultural tourism, while the least interest was shown in harmonic tourism, which was also disregarded by the largest proportion of respondents.

Analysis

The UNIANOVA one-way procedure for analysis of variance was used to answer the research questions and verify the research hypotheses (Francuz & Mackiewicz, 2012), with the explanatory variable being the level of wellbeing declared by the respondents. The characteristics of the level of wellbeing reported by the respondents are shown in the table below.

Table 5

Level of psychological wellbeing among the study group

| N | Important | 600 |

| Mean | 4.42 | |

| Median | 4.44 | |

| Dominant | 4.56 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.56 | |

| Skewness | -0.13 | |

| Standard error of skewness | 0.10 | |

| Kurtosis | -0.18 | |

| Standard error of kurtosis | 0.20 | |

| Minimum | 2.39 | |

| Maximum | 6.00 | |

| Percentile | 25 | 4.06 |

| 50 | 4.44 | |

| 75 | 4.83 | |

Source: author's own work.

The Polish adaptation of C. Ryff's Psychological Well-Being Scale, prepared by Karaś and Cieciuch in 2014, was used to measure the level of self-reported psychological well-being. The average well-being score was calculated based on the respondents' indications, using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ('strongly disagree') to 6 ('strongly agree') for 18 items. The mean level of psychological wellbeing recorded in the study group was M = 4.42 (SD = 0.56) points, while the lowest level of wellbeing of 2.39 points was reported by only 0.2% of the subjects. Similarly, the highest level of wellbeing of 6 points was achieved by only 0.2% of the subjects. The 25% of respondents with the lowest scores showed wellbeing of less than 4.06 points, and 25% of those with the highest level of wellbeing in the study group scored higher than 4.83 points. The distribution of wellbeing scores in the study group is left-skewed, meaning that there are more scores above the mean in the group than in normal distribution. The kurtosis value takes on a negative result, which means that the graph is platykurtic, i.e. the scores related to the subjects' wellbeing level show less concentration around the mean than is the case in normal distribution, which is consistent with the predictions for the study of psychological wellbeing and with measurements of wellbeing in different populations.

Considering the results of the UNIANOVA one-way procedure (Bedyńska & Cypryańska, 2013) for analysis of variance, it should be noted that statistically significant effects in shaping levels of psychological wellbeing were only recorded for the natural and cultural preferences of wellbeing tourism and for the perception of one's financial situation (Table 6). The other variables tested were not significant when differentiating levels of wellbeing.

Table 6

Results of a one-way analysis of variance on differences in wellbeing levels

| Source | Type III sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Significance | Partial Eta squared |

| Corrected model | 37.988a | 27 | 1.407 | 5.289 | 0.000 | 0.200 |

| Constant | 1260.355 | 1 | 1260.355 | 4737.943 | 0.000 | 0.892 |

| Sex | 0.076 | 1 | 0.076 | 0.287 | 0.593 | 0.001 |

| Age | 2.086 | 5 | 0.417 | 1.568 | 0.167 | 0.014 |

| Place of residence | 0.892 | 2 | 0.446 | 1.677 | 0.188 | 0.006 |

| Education | 0.202 | 2 | 0.101 | 0.381 | 0.684 | 0.001 |

| Financial situation | 12.255 | 3 | 4.085 | 15.357 | 0.000 | 0.075 |

| Luxury tourism | 0.389 | 2 | 0.195 | 0.731 | 0.482 | 0.003 |

| Nature tourism | 6.061 | 2 | 3.030 | 11.392 | 0.000 | 0.038 |

| Health tourism | 0.195 | 2 | 0.098 | 0.367 | 0.693 | 0.001 |

| Outdoor tourism | 0.163 | 2 | 0.081 | 0.306 | 0.737 | 0.001 |

| Harmonic tourism | 0.751 | 2 | 0.375 | 1.411 | 0.245 | 0.005 |

| Cultural tourism | 2.448 | 2 | 1.224 | 4.601 | 0.010 | 0.016 |

| Ecological tourism | 0.702 | 2 | 0.351 | 1.320 | 0.268 | 0.005 |

| Error | 152.160 | 572 | 0.266 | |||

| Total | 11890.389 | 600 | ||||

| Total (corrected) | 190.148 | 599 |

Note. a. R square = 0.200 (Adjusted R square = 0.162)

Calculated using alpha = 0.05

Source: author's own work.

Considering the results of the analysis of variance, it can be concluded that the effect of preference for nature tourism F(1.572) = 11.39, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.04, cultural tourism F(1.572) = 4.60, p = 0.010, ŋ2 = 0.02, and one's financial situation F(1.572) = 15.36, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.08, which, given the strength of effect measure ŋ2, explained the largest part of the variation in wellbeing, were comparable to the other significant variables. In order to test the differences in levels of perceived psychological wellbeing between those preferring a particular type of wellbeing tourism in more detail, a Bonferroni post hoc test was conducted, chosen because of the number of groups compared and its conservative approach. The results of the comparisons are shown in the table below.

Table 7

Results of the Bonferroni test showing differences in wellbeing among those who disregard, are neutral and prefer certain types of wellbeing tourism

| Nature tourism | Difference in means (I-J) | Standard error | significance | 95% confidence interval | ||

| lower limit | upper limit | |||||

| disregarding | neutral | -0.2327* | 0.06827 | 0.002 | -0.3966 | -0.0688 |

| preferring | -0.4518* | 0.06089 | 0.000 | -0.5979 | -0.3056 | |

| neutral | disregarding | 0.2327* | 0.06827 | 0.002 | 0.0688 | 0.3966 |

| preferring | -0.2191* | 0.04956 | 0.000 | -0.3381 | -0.1001 | |

| preferring | neutral | 0.4518* | 0.06089 | 0.000 | 0.3056 | 0.5979 |

| disregarding | 0.2191* | 0.04956 | 0.000 | 0.1001 | 0.3381 | |

| Cultural tourism | Difference in means (I-J) | Standard error | significance | 95% confidence interval | ||

| lower limit | upper limit | |||||

| disregarding | neutral | 0.0397 | 0.06102 | 1.000 | -0.1068 | 0.1862 |

| preferring | -0.2354* | 0.05602 | 0.000 | -0.3699 | -0.1009 | |

| neutral | disregarding | -0.0397 | 0.06102 | 1.000 | -0.1862 | 0.1068 |

| preferring | -0.2751* | 0.04851 | 0.000 | -0.3916 | -0.1586 | |

| preferring | disregarding | 0.2354* | 0.05602 | 0.000 | 0.1009 | 0.3699 |

| neutral | 0.2751* | 0.04851 | 0.000 | 0.1586 | 0.3916 | |

Note. Created based on observed averages/means.

The error component is the mean square (error) = 0.266.

*. The difference in means is significant at the level of 0.05.

Source: author's own work.

For those expressing a certain stance towards nature wellbeing tourism, the post hoc test revealed that there are significant differences in the level of perceived wellbeing between all groups. The level of perceived wellbeing of those disregarding nature wellbeing tourism in their decisions (M = 4.09, SD = 0.57) is significantly lower than the level of perceived wellbeing by neutral ones (M = 4.32, SD = 0.50), p = 0.002, and those preferring nature wellbeing tourism (M = 4.54, SD = 0.55), p < 0.001. The difference between those neutral and those preferring nature wellbeing tourism is also significant (p < 0.001).

For those expressing a certain stance towards cultural wellbeing tourism, the post hoc test revealed that there are significant differences in the level of perceived wellbeing between those disregarding and those preferring it, as well as between those neutral and those preferring this type of tourism. The level of perceived wellbeing of those who disregard cultural wellbeing tourism in their decisions (M = 4.31 SD = 0.55) is significantly lower than the level of perceived wellbeing of those who prefer it (M = 4.55, SD = 0.54), p < 0.001. Neutral persons (M = 4.27, SD = 0.56) also experience significantly lower levels of perceived psychological wellbeing than those who prefer cultural wellbeing tourism, p < 0.001. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the level of perceived psychological wellbeing between disregarders and neutrals, p = 1.00.

The Bonferroni post hoc test was also carried out to examine in more detail the differences in levels of perceived psychological wellbeing between those perceiving their financial situation in a particular way (Table 8).

Table 8

Results of the Bonferroni test showing differences in wellbeing among those who perceive their financial situation differently

| Perception of one's own financial situation | Difference in means (I-J) | Standard error | significance | 95% confidence interval | ||

| lower limit | upper limit | |||||

| 1. I can afford everything without special sacrifices. | 2 | 0.1162 | 0.05337 | 0.180 | -0.0251 | 0.2575 |

| 3 | 0.3300* | 0.06364 | 0.000 | 0.1616 | 0.4985 | |

| 4 | 0.5188* | 0.09368 | 0.000 | 0.2708 | 0.7668 | |

| 2. I live frugally and thus have enough money for everything. | 1 | -0.1162 | 0.05337 | 0.180 | -0.2575 | 0.0251 |

| 3 | 0.2139* | 0.05466 | 0.001 | 0.0692 | 0.3586 | |

| 4 | 0.4026* | 0.08783 | 0.000 | 0.1701 | 0.6351 | |

| 3. I live very frugally in order to have money for more significant purchases. | 1 | -0.3300* | 0.06364 | 0.000 | -0.4985 | -0.1616 |

| 2 | -0.2139* | 0.05466 | 0.001 | -0.3586 | -0.0692 | |

| 4 | 0.1888 | 0.09442 | 0.276 | -0.0612 | 0.4387 | |

| 4. I do not have enough money for all my basic needs. | 1 | -0.5188* | 0.09368 | 0.000 | -0.7668 | -0.2708 |

| 2 | -0.4026* | 0.08783 | 0.000 | -0.6351 | -0.1701 | |

| 3 | -0,1888 | 0.09442 | 0.276 | -0.4387 | 0.0612 | |

Note. Created based on observed averages/means.

The error component is the mean square (error) = 0.266.

*. The difference in means is significant at the level of 0.05.

Source: author's own work.

The post hoc test revealed that there are significant differences in the level of perceived wellbeing between those with different perceptions of their financial situation. Respondents who believe that they can afford everything without special sacrifices (1) achieve significantly higher levels of wellbeing (M = 4.58, SD = 0.57) than respondents from group 3 - those living very frugally (M = 4.24, SD = 0.52), p < 0.000 and group 4 - those who do not have enough money for all their basic needs (M = 4.06, SD = 0.57), p < 0.000. There was no significant difference in the level of perceived wellbeing between group 1 and group 2, i.e. respondents who can afford everything thanks to frugal living (M = 4.46, SD = 54). Significantly higher levels of perceived wellbeing are experienced by respondents from group 2 compared to respondents from group 3 (p < 0.001) and group 4 (p < 0.000). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the level of perceived psychological wellbeing between respondents living very frugally to put aside/have money for more significant purchases (group 3) and respondents from group 4.

Results

The research hypotheses were verified using analysis of variance, with the first hypothesis, formulated as "the level of demonstrated psychological wellbeing of tourists varies according to their stated preferences in the area of wellbeing tourism", partially confirmed. The level of perceived psychological wellbeing differed significantly for two types of wellbeing tourism - nature tourism and cultural tourism. Out of the hypotheses from H1a to H1e, only hypothesis H1e was confirmed - "the level of demonstrated psychological wellbeing of tourists varies according to perception of one's own financial situation". A significant factor differentiating the level of perceived psychological wellbeing is the perception of one's own financial situation, while psychological wellbeing was not significantly statistically related to the other variables examined - gender, age, place of residence, educational level of the surveyed individuals.

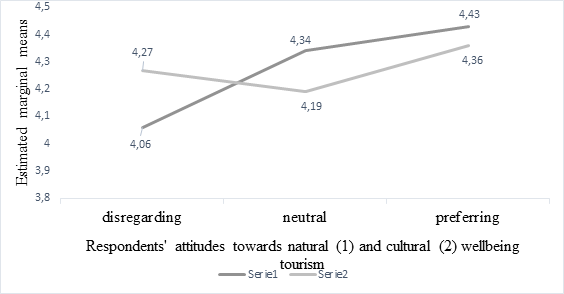

When answering the posed research question "between which groups preferring a certain type of wellbeing tourism are there differences related to the average level of mental wellbeing?", it is also necessary to refer to the results of the analysis of variance. A graphical representation of the differences in the level of psychological wellbeing, taking into account estimated marginal means of the level of wellbeing among the disregarders, neutrals and those preferring natural and cultural wellbeing tourism, is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2

A comparison of the estimated marginal means of the level of wellbeing among the disregard, neutral and preference groups of natural and cultural wellbeing tourism

Source: author's own work.

Significant differences in the respondents' levels of psychological wellbeing only occurred when they were divided within the natural and cultural wellbeing tourism preferences, while the preferences revealed towards the other types of wellbeing tourism were not significant in differentiating the respondents' levels of psychological wellbeing.

Discussion

Tourists' awareness, expectations, attitudes, fears and behaviours in the post-covid and war reality are changing. This also calls for a paradigm shift in tourism research, and an increased interest in research areas that arise from changes in the psychological condition of individuals. The results of such research can form the basis for changes in the work of the tourism industry, and modifying tourism offers to take into account the impact of specific factors supporting psychological wellbeing can result in increased tourist engagement, satisfaction and motivation to enhance their tourism experience.

Differences between the groups of individuals preferring natural and cultural wellbeing tourism were found to be significant in terms of their levels of psychological wellbeing, which may be due to the applied division of wellbeing tourism and the popularity of both constructs among tourists, based on their greatest familiarity and liking (Fennis & Stroebe, 2021).

The detected effects of preferences within natural and cultural wellbeing tourism and the importance of perceptions of one's own financial situation in shaping tourists' sense of psychological wellbeing explain the small area of variation in wellbeing, which makes us wonder about further variables that influence the level of the eudaimonistic psychological wellbeing of tourists. However, due to the scale of tourist activity, which, according to Statistics Poland (GUS), concerned 22,198,972 tourists in Poland in 2021, this variability may involve hundreds of thousands of people (GUS, 2022).

Conclusions

Do Polish tourists want wellbeing tourism? - a clear answer cannot be given to the question posed in the title of this article. Wellness tourists, as observed in the study, prefer two types of tourism, referred to as nature tourism and cultural tourism, and the descriptions of both types relate to experiencing specific situations. Tourists preferring nature tourism look for interesting places where they can experience something new and unexpected while exploring the local countryside, taking advantage of the available opportunities. On the other hand, tourists preferring cultural tourism desire culturally interesting places where they can focus, read a book, observe the beauty of local nature, or admire monuments. Taking into account these two most popular indications, it is necessary to determine what other aspects of wellbeing tourism are important for tourists seeking such experiences.

The study aims to explore the relationship between psychological wellbeing and choices related to wellness tourism, as wellness tourism offers significant opportunities for shaping an individual's mental well-being. This research can serve as inspiration for entrepreneurs operating in the wellness tourism industry to incorporate information about the impact of such leisure activities on mental wellbeing into their marketing communication, and could also encourage them to seek and create services within the realm of wellness tourism that contribute to the enhancement of well-being among tourists.

Limitations

The main limitation of the study was the use of a quota sampling approach among participants of the research panel, which prevents us from applying the results to the total population of Polish tourists. Another limitation of the study was also the use of an abbreviated version of the Ryff psychological wellbeing questionnaire, which this was for practical reasons, although using the standard version with 84 items would have allowed for a more in-depth examination of tourists' psychological wellbeing across its six dimensions and relating specific dimensions of wellbeing to preferences for specific types of wellbeing tourism, and would also have been important in the context of the psychological wellbeing of individuals to address the tourism experience as a whole, which is certainly a broad area for research.

References

- Aebli, A., Volgger, M., & Taplin, R. (2022). A two-dimensional approach to travel motivation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(1), 60-75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1906631

- Baehre, S., O'Dwyer, M., O'Malley, L., & Story, V. M. (2022). Customer mindset metrics: A systematic evaluation of the net promoter score (NPS) vs. alternative calculation methods. Journal of Business Research, 149, 353-362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.048

- Bassi, M., Carissoli, C., Beretta, S., Negri, L., Fianco, A., & Delle Fave, A. (2022). Flow experience and emotional well-being among Italian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Psychology, 156(6), 395-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2022.2074347

- Bedyńska, S., & Cypryańska, M. (2013). Statystyczny drogowskaz 2. Praktyczne wprowadzenie do analizy wariancji. Wydawnictwo Akademickie SEDNO.

- Berbekova, A., & Uysal, M. (2021). Wellbeing and quality of life in tourism. In J. Wilks, D. Pendergast, P. A. Leggat, & D. Morgan, D. (Eds.), Tourist health, safety and wellbeing in the new normal (pp. 243-268). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5415-2_10

- Bęben, R., Kuczamer-Kłopotowska, S., Młynkowiak-Stawarz, A., & Półbrat, I. (2021). Tourist behavioral intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The role of reactance, perceived risk and protection motivation. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, 12, 2130-2149.

- Bhullar, N., Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2013). The nature of well-being: The roles of hedonic and eudaimonic processes and trait emotional intelligence. The Journal of Psychology, 147(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2012.667016

- Bolotnikova, I., Kucherhan, Y., Vyshnyk, O., Shyrobokov, Y., & Dzykovych, O. (2023). Psychological well-being of a pedagogue in the conditions of war. Revista Eduweb, 17(2), 149-160. https://doi.org/10.46502/issn.1856-7576/2023.17.02.13

- Bosnjak, M., Brown, C. A., Lee, D.-J., Yu, G. B., & Sirgy, M. J. (2016). Self-expressiveness in sport tourism: Determinants and consequences. Journal of Travel Research, 55(1), 125-134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514535845

- Buckley, R. (2019). Therapeutic mental health effects perceived by outdoor tourists: A large-scale, multi-decade, qualitative analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 77, 164-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.017

- Buckley, R. (2020). Nature tourism and mental health: parks, happiness and causation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1409-1424. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1742725

- Buckley, R. (2022). Tourism and mental health: Foundations, frameworks, and futures. Journal of Travel Research, 62(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875221087669

- Chon, K., & Olsen, M. D. (1991). Functional and symbolic congruity approaches to consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction in tourism. Journal of the International Academy of Hospitality Research, 3, 2-22.

- Chudzicka-Czupała, A., Hapon, N., Ho Chun Man, R., Li, D., Żywiołek-Szeja, M., Karamushka, L., Grabowski, D., Paliga, M., McIntyre, R.S., Chiang, S., Pudełek, B., Chen, Y., & Yen, C. (2023). Associations between coping strategies and psychological distress among people living in Ukraine, Poland, and Taiwan during the initial stage of the 2022 War in Ukraine. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022.2163129

- Cini, F., Kruger, S., & Ellis, S, (2013). A model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations on subjective well-being: The experience of overnight visitors to a national park. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 8(1), 45-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-012-9173-y

- Daly, M., Sutin, A., & Robinson, E. (2020). Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Psychological Medicine, 52(13), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720004432

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being. The sciences of happiness and proposal for a national index. American Psychologists, 55(1), 34-43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

- Dolnicar, S., Lazarevski, K., & Yanamandram, V. (2013.) Quality of life and tourism: A conceptual framework and novel segmentation base. Journal of Business Research, 66(6), 724-729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.09.010

- Fakfare, P., Lee., J.-S., & Ryu, K. (2020). Examining honeymoon tourist behavior: multidimensional quality, fantasy, and destination relational value. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(7), 836-853. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2020.1835786

- Farkic, J., Isailovic, G., & Taylor, S. (2021). Forest bathing as a mindful tourism practice. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 2(2), 100028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2021.100028

- Fennis, B., & Stroebe, W. (2021). The psychology of advertising (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Filep, S., Moyle, B. D., & Skavronskaya, L. (2022). Tourist wellbeing: Re-thinking hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480221087964

- Francuz, P., & Mackiewicz, R. (2012). Liczby nie wiedzą skąd pochodzą. Przewodnik po metodologii i statystyce nie tylko dla psychologów. Wydawnictwo Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego.

- GUS. (2022, June 30). Turystyka w 2021 r. https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/kultura-turystyka-sport/turystyka/turystyka-w-2021-roku,1,19.html

- GUS. (n.d.). Wyniki badań bieżących. Retrieved October 4, 2022, from https://demografia.stat.gov.pl/bazademografia/Tables.aspx

- Hannan, T., Keech, J. J., Cassimatis, M., & Hamilton, K. (2021). Health psychology, positive psychology and the tourist. In J. Wilks, D. Pendergast, P. A. Leggat, & D. Morgan (Eds.), Tourist health, safety and wellbeing in the new normal (pp. 221-242). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5415-2_9

- Hartwell, H., Fyall, A., Willis, C., Page, S., Ladkin, A., & Hemingway, A. (2018). Progress in tourism and destination wellbeing research. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(16), 1830-1892. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1223609

- Heszen-Cielińska, I., & Sęk, H. (2020). Psychologia zdrowia. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

- Io, M.-U., & Peralta, R. L. (2022). Emotional well-being impact on travel motivation and intention of outbound vacationers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Leisure/Loisir, 46(4), 543-567. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2022.2032809

- Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. Basic Books. https://doi.org/10.1037/11258-000

- Kállay, É., & Rus, C. (2014). Psychometric properties of the 44-item version of Ryff's Psychological Well-Being Scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 30(1), 15-21. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000163

- Karaś, D., & Cieciuch, J. (2017). Polska adaptacja Kwestionariusza Dobrostanu (Psychological Well-being Scales) Caroll Ryff. Roczniki Psychologiczne, 20(4), 815-853.

- Kessler, D., Lee J.-H., & Whittingham, N. (2020). The wellness tourist motivation scale: a new statistical tool for measuring wellness tourist motivation. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 3(1), 24-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2020.1849930

- Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D., Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 1007-1022. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007

- Kim, D., Lee, C.-K., & Sirgy, M. J. (2016). Examining the differential impact of human crowding vs. spatial crowding on visitor satisfaction. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 33(3), 293-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1024914

- Kim, H., Woo, E., & Uysal, M. (2015). Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tourism Management, 46, 465-476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.002

- Koole, S. L., & Rothermund, K. (2022). Coping with COVID-19: Insights from cognition and emotion research. Cognition and Emotion, 36(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2022.2027702

- Kruger, S., Sirgy, M. J., Lee, D.-J., & Yu, G. (2015). Does life satisfaction of tourists increase if they set travel goals that have high positive valence? Tourism Analysis, 20(2), 173-188. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354215X14265319207353

- Lee, D. J., Kruger, S., Whang, M.-J., Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J. (2014). Validating a customer wellbeing index related to natural wildlife tourism. Tourism Management, 45, 171-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.04.002

- Lee, H., Lee, J., Chung, N., & Koo, C. (2018). Tourists' happiness: Are there smart tourism technology effects? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(5), 486-501. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1468344

- Lee, D.-J., Sirgy, M. J., Yu., G. B., & Chalamon, I. (2015). The well-being effects of self-expressiveness and hedonic enjoyment associated with physical exercise. Applied Research Quality Life, 10, 141-159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9305-7

- Lewis, S., Freeman, M., van Ommeren, M., Chisholm D., Gascoigne Siegl, O., Kestel, D. (Eds.). (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338

- Li, J., Ridderstaat, J., & Yost, E. (2022). Tourism development and quality of life interdependence with evolving age-cohort-based population. Tourism Management, 93, 104621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104621

- Lindell, L., Dmitrzak, M., Dziadkiewicz, A., Jönsson, P. M., Jurkiene, A., Kohnen, J., Melbye, K., Steimle, M., & Verstift, S. (2022). Good practices in wellbeing tourism. Innovative and conscious entrepreneurship development in accommodation, gastronomy, products, services & places. Linnaeus University.

- Lindell, L., Sattari, S., & Höckert, E. (2021). Introducing a conceptual model for wellbeing tourism - going beyond the triple bottom line of sustainability. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 5(1), 16-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2021.1961077

- Luo, Y., Lanlung, C., Kim, E., Tang, L. R., & Song, S. M. (2018). Towards quality of life: The effects of the wellness tourism experience. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(4), 410-424. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1358236

- Lück, M., & Aquino, R. S. (2021). Domestic nature-based tourism and wellbeing: A roadmap for the new normal? In J. Wilks, D. Pendergast, & P. A. Morgan (Eds.), Torist health, safety and wellbeing in the new normal (pp. 269?-292). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5415-2_11

- Manchiraju, S. (2020). Psychometric evaluation of the Ryff's Scale of psychological wellbeing in self-identified American entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14, e00204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00204

- McMahan, E.A., & Estes, D. (2011). Hedonic Versus eudaimonic conceptions of well-being: Evidence of differential associations with self-reported well-being. Social Indicators Research, 103, 93-108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9698-0

- Neal, J. D., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2007). The effect of tourism services on travelers' quality of life. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 154-163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507303977

- Ng, J. Y., Ntoumanis, N., Thogersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E., Ryan, R., Duda, J. L., & Williams, G. (2012). Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(4), 325-340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612447309

- Ng, W., & Kang, S. H. (2022). Predictors of well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The importance of financial satisfaction and neuroticism. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(7), 2771-2789. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22795

- Ntoumanis, N., Ng, Y., Prestwich, A., Quested, E., Hancox, J., Thogersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E., Ryan, R., Lonsdale, C., & Williams, G. (2020). A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: Effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health Psychology Review, 15(2), 214-244. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2020.1718529

- Pilar Matud, M., del Pino, M. J., Bethencourt, J. M., & Lorenzo, D. E. (2022). Stressful events, psychological distress and well-being during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A gender analysis. Applied Research Quality Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-022-10140-1

- Pope, E. (2018). Tourism and wellbeing: transforming people and places. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 1(1), 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2018.1438559

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141-166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is not everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069-1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- Ryff, C. D. (2013). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10-28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263

- Ryff, C. D. (2017). Eudaimonic well-being, inequality, and health: Recent findings and future directions. International Review of Economics, 64, 159-178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-017-0277-4

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Prawdziwe szczęście. Wydawnictwo Media Rodzina.

- Sirgy, M. J. (2019). Promoting quality-of-life and well-being research in hospitality and tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1526757

- Sirgy, M. J., Lee, D.-J., Yu, G. B. (2018). Self-congruity theory in travel and tourism: Another update. In N. Prebensen, M. Uysal, & J. Chen (Eds.), Creating experience value in tourism (pp. 57-69). CABI Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786395030.0057

- Smith, M. K., & Diekmann, A. (2017). Tourism and wellbeing. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006

- UNWTO. (2022). World Tourism Barometer (English version). https://doi.org/10.18111/wtobarometereng.

- Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., & Kim, H. (2016). Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Management, 53, 244-261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

- Vanaken, L., Bijttebier, P., Fivush, R., & Hermans, D. (2022). Narrative coherence predicts emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: a two-year longitudinal study. Cognition and Emotion, 36(1), 70-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2021.1902283

- Vázquez, C., Hervás, G., Rahona, J. J., & Gómez, D. (2009). Psychological well-being and health. Contributions of positive psychology. Annuary of Clinical and Health Psychology, 5, 15-27.

- Voigt, C., Howat, G., & Brown, G. (2010). Hedonic and eudaimonic experiences among wellness tourists: An exploratory enquiry. Annals of Leisure Research, 13(3), 541-562, https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2010.9686862

- Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., & Conti, R. (2008). The implications of two conceptions of happiness (hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia) for the understanding of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 41-79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9020-7

- Willis, C. (2015). The contribution of cultural ecosystem services to understanding the tourism-nature-wellbeing nexus. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 10, 38-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2015.06.002

- Yu, J., Smale, B., & Xiao, H. (2021). Examining the change in wellbeing following a holiday. Tourism Management, 87, 104367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104367

- Zins, A. H., & Ponocny, I. (2022). On the importance of leisure travel for psychosocial wellbeing. Annals of Tourism Research, 93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103378

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6398-8333

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6398-8333