Informacje o artykule

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em108.1700

W wersji drukowanej czasopisma artykuł znajduje się na s. 4-13.

Pobierz artykuł w wersji PDF

Pobierz artykuł w wersji PDF

Abstract in English

Abstract in English

Jak cytować

Fridman, L., Tila, D., Haas, A., Zipper, T., Neuhold, P., Mendel, I., & Brogun, D. Y. (2025). Team as Support (TAS): How Building Psychological Safety into Classroom Design Led to Higher Performance and More. e-mentor, 1(108), 4-13. https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em108.1700

E-mentor nr 1 (108) / 2025

Spis treści artykułu

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Imagine!

- How is Tas Organized in the Classroom?

- What are the Key Ideas that Distinguish Tas?

- Student Surveys: The Impact of Tas

- Teacher and Student Experiences

- Practical Challenges

- Conclusions and Next Steps

- References

Informacje o autorach

Przypisy

1 Cited in Amy C. Edmundson’s The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation and Growth. Wiley, 2018.

2 Citations from student reflective writing are included here and else where because the “voice” of the student is revealing of their experience. The quotes are marked with P1, P2, etc.

Team as Support (TAS): How Building Psychological Safety into Classroom Design Led to Higher Performance and More

Lea Fridman, Dorina Tila, Amy Haas, Tauba Zipper, Petra Neuhold, Iris Mendel, Dmitry Y. Brogun

Abstract

The pedagogy described in this paper has been transformative in European as well as in New York classrooms. “Team As Support” (TAS) is a structured and replicable teaching model focused on creating “psychological safety” within permanent semester-long teams of 6-7 students. Our eight years of teacher and student experience and our preliminary data make clear how the removal of a fear of criticism along with the creation of a student-driven structure of support brings the student greater freedom in expressing and testing ideas, exposure to multiple points of view, improved metacognition, critical thinking, engagement and much more. Combining elements of Team-Based Learning (TBL) and the Team Management and Leadership Program (TMLP), TAS uniquely emphasizes trust, kindness, and community as central to academic success and personal growth.

At the same time, this paper addresses a critical gap in Higher Education studies. “Psychological safety” is well established in research on performance and innovation across multiple fields (business, leadership, management, psychology, social psychology, trauma studies, medicine) although notably absent as in Higher Education. Our work and data on TAS open a new direction in Higher Education studies, work that is supported by research in Higher Education itself on the impact of fear on cognition, critical thinking and memory as well as by the established insights on the benefits of collaborative learning and on the emotional dimensions of learning. The emphasis in TAS on the key ideas of ‘possibility,’ support and breakdown as the path to breakthrough is a unique and innovative toolbox of a growth mindset valued across Higher Education.

Keywords: psychological safety, higher education, workforce-ready skills, transformative pedagogy, Social-Emotional Learning (SEL), teamwork strategies

Introduction

No passion so effectively robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as fear.

Edmund Burke, 17561

Many times each of us had an issue with something that made us really sad and hopeless, but my team was always there to help. We text all the time through messages and make zoom conversations before we start our assignment. (P1)2

The research is extensive and well-documented. Over one thousand studies on leadership, management and business support the view that the highest-performing groups/teams are those that share a key characteristic: psychological safety (Duhigg, 2016a; Duhigg, 2016b; Edmondson & Shike, 2014; Kish-Gephart et al., 2009; Newman et al., 2017). This is fundamental in the fields of business, management, leadership, psychology, trauma studies, social psychology and medicine (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2019; Edmondson, 1999; Herman, 1992; Porges, 2011; Tulshyan, 2021; Wanless, 2016). Surprisingly, there is almost no focus on psychological safety in teamwork and its role in the classroom in higher education, although educational studies into related areas of the social and emotional dimensions of learning are extensive (Deutsch, 1949; Johnson & Johnson, 1989; Piaget, 1970; Vygotsky, 1978). Team as Support (TAS) is a transformative pedagogy that addresses this gap. Our data and eight years of implementation open an important new direction for higher education practice and research, one that is just beginning to attract interest. (Davidson & Katopodis, 2022; Lory, 2022).

TAS is a pedagogy that revolves around creating psychological safety or a “shared belief held by members of a team that it’s OK to take risks, to express their ideas and concerns, to speak up with questions, and to admit mistakes - all without fear of negative consequences” (Gallo, 2023). The approach has been a gamechanger for students taking our classes and for us as instructors in both in-person and, importantly, online teaching situations (Roberts-Grmela, 2023). As applied to higher education, the research suggests, and the experience of both teachers and students for the past eight years confirms, that nurturing psychological safety, trust and intimacy within permanent, semester-long student teams enhances academic outcomes, course engagement and satisfaction, while providing students with desperately needed social support, training them in effective collaboration and preparing them to be part of a workforce (Aronson, 2020; Clark, 2020). This is a pedagogy that teaches students how to collaborate, how to take initiative and how to lead. It is an approach that creates real connection, trust and bonding within diverse student teams. It gives students (and their instructors!) a language, metacognitive tools and real- world practice in creating possibility and opportunity out of failure, or, in the language of this pedagogy, breakthrough out of breakdown.’ It does all this by actively fostering support, kindness, generosity and a true sense of community in the work of the classroom, to far-reaching effect. See Appendix A for recent discussions of kindness, learning and the emotional life of the student. (Denial, 2024; Gorny-Wegrzyn, et al., 2022; Simons & Almasy, 2019; https://www.qc.cuny.edu/cetll/pedagogy-of-kindness-building-a-community-of-inquiry/; https://www.qc.cuny.edu/cetll/the-pedagogy-of-kindness-the-discussion-continues/; https://www.qc.cuny.edu/cetll/udl-approach-across-cuny/).

Imagine!

What if every student in your class had their own support team of five or six peers - a permanent, semester-long team that allowed them to deepen bonds of trust over the course of a semester - as they navigated the demands of college, work, family, the aftermath of Covid and online learning? What if students, so many of them still suffering from the isolation brought on by this extended COVID period of crisis, were connected to their teams through chats and virtual meetings and, because of the trust, familiarity and sense of safety encouraged within this specific cohort design, could easily lean on one another to understand and prepare for assignments, brainstorm without fear of criticism or of “looking bad” to others and even make new friends? What would the impact of such a classroom design be for the online student; for critical thinking and metacognitive skills that come with the freedom to express ideas without fear of criticism and with exposure to multiple points of view; for learning outcomes, collaborative skills, workforce development, retention, course engagement and satisfaction: in other words, for the lives, hopes and dreams of the students we serve?

What I like the best about The Power Rangers is the sense of belonging. We all instantly tried to make the best of our group. We started to communicate and even found commonality between each other. We began with our interests and what we wanted to do in life. . . . It was an immediate feeling of safeness and comfort each and every time our group comes together. We tried to really make each other feel as if they’re heard and contributing to the group. (P2)

While psychological safety has not until now entered the vocabulary of higher education as a focus of research, its opposite, fear, has been widely studied. This is pointedly underlined in the opening citation from Edmunde Burke to this article. Today – almost eight centuries later – fear is well recognized for the ways in which it activates the amygdala, narrowing focus at the expense of reasoning, critical thinking, openness and problem-solving (LeDoux, 2000; Medina, 2008). The direct impact on the brain and on critical thinking has been studied in works by John Bransford as well as by Richard S. Lazarus and Susan Folkman (Bransford et al., 2000; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In his influential What the Best College Teachers Do, Ken Bain (2004) looks at fear and anxiety as barriers to transformational and deep learning. The issue of fear in the development of critical thinking has been studied by Stephen Brookfield (1987; 2012) as well as in works by Patricia King and Karen Kitchner (1994; 2002). Carol Dweck (2007), best known for her work on fixed vs. growth mindsets, directly addresses the fear of failure as it manifests itself in identity issues and affects academic performance. Similarly, Claude Steele and others have studied identity issues and the role of fear in students from marginalized backgrounds (Cohn-Vargas & Steele, 2013; Steele, 1997). The list goes on.

Being part of a team can help overcome fear and shyness, and improve confidence. Being part of a team that you feel comfortable with can help you be more talkative. Being part of a team gives you the opportunity to help others if they need anything. Having a team also gives you the opportunity to meet new people. I personally learned and gained a lot from being part of a team. I never had this opportunity before and I definitely enjoyed it. Being part of a team made my learning experience more enjoyable. (P3)

The pedagogy of TAS incorporates key features from two well-established approaches to teamwork – Team-Based Learning (TBL) and the Team Management and Leadership Program (TMLP) - but with a fundamentally new focus on the principle of psychological safety. Whereas TBL organizes students in permanent semester-long teams around a principle of accountability towards the team for the purpose of course mastery and is well known in academic settings, Landmark’s TMLP approach focuses on ideas of possibility, of creating opportunity and of treating breakdowns as the path to breakthroughs within corporate and business settings (Elizade-Utnick, n.d.; LeGassick et al., 2011; Michaelsen et al., 2004; Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008; Sibley et al., 2014; Zapolski & DiMaggio, 2011; Zeffron & Logan, 2011). Importantly, Landmark emphasizes leadership and the role and responsibilities of a team leader.

From 2008 onwards, Kingsborough faculty, intensively trained in both methodologies, used a combination of these two teamwork approaches in the classroom, and this continued until 2016. Newly aware of the critical link between psychological safety and performance, instructions given to our students shifted from you are accountable to your team (spotlight on the self) to your job is to support the work of your teammates (spotlight on others) (Duhigg, 2016a; Duhigg 2016b). With these new instructions, TAS came into being. See Appendix B for a history of the evolution of TAS and detailed comparison of the common and contrasting features of TAS.

TAS redirects the attention of students from the self to others; from students experiencing themselves as solo players out to earn a good grade, to experiencing themselves as an integral part of a team. Instead of working alone and in competition with others, students took the initiative to creatively connect to and support the work of others (Buettner, 2012; Murthy, 2023; Shagholi et al., 2010). It was this subtle but dramatic shift that made all the difference in the experiences of teachers and students in our TAS classes. It accounts for the corroborating data from both faculty observation and student surveys we have collected, data - albeit at this time preliminary - that now adds higher education to the list of fields to which the study of psychological safety is clearly and deeply relevant (see Appendix B).

Importantly, TAS is not a variation on group work (Fiechtner & Davis, 1985; LaBeouf et al., 2016; Oakley et al., 2004; Taylor, 2011). In TAS pedagogy, instructors do not create an assignment, give it to a team and collect the work. TAS requires the familiarity and trust that is nurtured over a full semester. A real psychic infrastructure of safety takes time and repeated experiences of support, generosity and kindness within a team to make a difference, to break down the barriers of fear, open minds to new ideas and create meaningful results. How is this accomplished? How is a TAS class organized? What kinds of assignments provide the best support for TAS? What are its guiding ideas and procedures? See Appendix D for key teaching materials.

My team honestly made everything easier for me. As I stated before, being able to say I don’t understand something and we all come together to help each other understand was very satisfying. They allowed me to think outside of the box. Sometimes I have my own understanding of things and they allow me to see different points of view. (P4)

How is Tas Organized in the Classroom?

Seating, Team Name and Social Media

In the classroom, students sit in teams, in circles facing one another throughout the class and throughout the semester - and not in a traditional row formation facing the instructor. This re-designing of the classroom space powerfully facilitates team bonding, discussion and presentations; it creates what Charles Duhigg, in Smarter, faster, better (2016a), calls a shifting of the locus of control. That shift, from reliance on the instructor to a student-and team-centered class, brings with it constant opportunities for student independence and initiative in learning, for the support of the members of their team, and thus, also, for improved academic outcomes, all of which are echoed in the brief but illustrative comments from students on their experiences cited in italics throughout this paper. See Appendix D for key teaching materials that detail this teaching design.

Students are placed into groups of between six and seven students on the first day of class. Instructors organize these groups alphabetically or according to the availability of students for video conferences and to chat within their team. Teamwork is prominently featured and detailed in the course syllabus. At their first meeting, the teams select the social media platform for their team ‘chat.’ Chats and virtual meetings are a critical form of support that allows students to help one another, ask questions, exchange ideas, prepare for examinations and assignments and bond with one another. In one case, a student checked her phone following surgery for a leg injury and saw messages from her team. It made me happy, she said when she spoke to her instructor.

An important activity (and icebreaker) in the first week of class is to ask each team to brainstorm a name for their team (chosen names include The Giraffes, Phantom Fugitives, C’s Get Degrees, and The Scholars). Once a team has agreed on a team name, students write their team’s name on all submitted work.

Rotating Team Leader and Chief Technology Officer

In this model of teamwork, leadership rotates weekly and, for the sake of simplification, alphabetically by last name. It is the job of the Team Leader to lead in the support of their team, to reach out to students who are absent, and to be attentive to the needs of individuals within their team and creative in offering support. And it is the job of team members to support their Team Leader in that role. Some instructors find it helpful to have one student act as the Chief Technology Officer of their team. This provides an extra layer of support for students who struggle with technology and with the tech requirements of the course and college. In reflective writing, students continually comment on the usefulness of the experience of leadership. One student surprised his professor, telling her that he was a pre-law student and that the opportunity to be a Team Leader was contributing to his future career!

At times, shy students have said they did not want to be Team Leaders, only to be told by the professor that this feature was in the syllabus and required. In almost all cases, shy students did well as Team Leaders and became visibly more comfortable around others and with their leadership role.

Weekly Reporting: Possibility and Outgoing Team Leader Report

At the beginning of their leadership week, the Team Leader provides their instructor with several sentences clarifying the Possibility they plan to create for their team. The Possibility includes a twofold intention or focus for the week: one that is academic (we will meet to prepare for an upcoming quiz; we will help one another with editing of an essay that is due) and one that promotes team bonding and psychological safety (we will share vacation plans; we will talk about the challenges we face above and beyond ‘classwork’). The Possibility represents a serious metacognitive assessment on the part of the Team Leader of where members are at in their course work, what the most effective academic intervention/ focus might be for that week and how best to enhance the bonding and sense of safety within the team.

At the end of the leadership week, the Team Leader also hands in an Outgoing Team Leader Report consisting of two paragraphs. The first is an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of their team. The second details the Team Leader’s creative contributions to their team: how did they make a difference for their teammates; what were the challenges; to what extent were they successful?

The Outgoing Team Leader Report has proven to be a fascinating document. The report is a behind-the-scenes view of what is going on in a particular team (and in a class), which is normally not visible to the instructor. Instructors have learned about students who, during the COVID pandemic, were absent from class but very active in their teams. They have learned about initiatives undertaken by students on behalf of one another that they could not have otherwise known about.

There are a few things I love about my team. Me and my teammates show leadership, determination, and always being able to step forward towards our future. I like how you put me and my team mates together as one because we really see ourselves being friends in the next few years. (P5)

What are the Key Ideas that Distinguish Tas?

Possibility

To begin with, TAS is embedded in the language of possibility. It is important for the instructor to find ways to provide students with a growth mindset of possibility that they can apply to their own lives. The notion of possibility is a theme of the course and includes, as described above, the weekly Possibility submitted by the Team Leader. Possibility is thus embedded into a continual refashioning of intentions by each new Team Leader on a weekly basis, with the emphasis on each member making a difference for the others on their team and in training students in the practical steps needed to create breakthroughs and new possibilities out of breakdown, missed opportunity and failure.

Support and Psychological Safety

One early study of psychological safety was of nursing teams. Amy Edmundson, then a graduate student (now the Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School) was puzzled by the fact that nursing teams with the best records of performance also had the worst records of error! It turned out that the nursing teams in which it felt safe to report errors were then able to correct their errors and thus save lives. This was not true for nursing teams which lacked the psychological safety needed to report error in the first place (Baskin, 2023; Carmeli & Gittell, 2009; Edmondson, 1996; Edmondson, 2018). This insight guided decades of subsequent empirical research for which Edmundson is lauded and has been widely adopted across many fields. Our experience and data suggest that Edmundson’s remarkable insight is both transferable and replicable in the higher education context.

A psychic and practical infrastructure of deep support and safety among students is key to the creation of ideal communities (teams), the mastery of course material, the learning of collaborative skills, the reaching of higher levels of initiative, student satisfaction and workforce development, and, importantly, the improvement of mental health. Interestingly, in informal writing about their team experiences, students often wrote about mental health and stress reduction as one of the impacts of TAS over the semester (Bellows, 2022; Dempsey, n.d.; George & Strauss, 2022). But how is the subtle but critical transition from merely working together, with its highs, lows and inevitable stresses, to a sense of safety and trust accomplished?

It is important to introduce reading and discussion of the idea of psychological safety at the outset of the semester. In one case, after reading the 2016 NYT Magazine article What Google Learned from Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team by Charles Duhigg (2016b), a student commented, Oh, now I understand why you put us into teams! Amy Gallo’s What is Psychological Safety (2023) is another insightful discussion of psychological safety that students have found helpful. It has proven instructive to ask students to reflect on the sense of safety they felt to speak up and share ideas in their other classes and to rate their sense of safety in two or three of those other classes on a scale of one to ten. The experience can be eye-opening for students as well as for instructors. It helps the student gain awareness of how feeling unsafe impacts learning, critical thinking, the sharing of ideas, engagement, academic performance and their overall college experience.

As helpful as our own college resources are to support students at Kingsborough, a two-year college that is part of the City University of New York, nothing comes close to the 24/7 support that is built into the TAS classroom for every student. This support is especially critical for the full and part-time students who work and for those who also juggle parental and family responsibilities (Perna, 2010; Perna & Odle, 2020.). One of our Kingsborough instructors was especially gratified when an entire class of students, all of whom were employed full-time, passed her course with good grades. Only teamwork framed as support could have made this happen.

Breakdown as the Path to Breakthrough

In The New College Classroom Catherine Davis and Christina Katopodis (2022), write about TAS, and how in this pedagogy, “breakdowns become opportunities for breakthroughs. Students gain a sense of comfort in taking risks. Shy students overcome their shyness knowing they are safe from embarrassment or shame.” Training students to see breakdowns as the path to breakthrough is a key idea in the TAS approach imported from Landmark’s TMLP. It takes the sting out of the failures and self-flagellations that students often subject themselves to when upset by a grade or other failure. It helps the student take a step back, assess a disappointing situation, and brainstorm the most effective way to create a new possibility. It teaches students what Amy Edmundson calls, in the title of her new book, Right Kind of Wrong: the Science of Failing Well (Edmundson, 2023). In it, Edmondson distinguishes between failures that are springboards to better ideas (or breakthroughs) and failures that remain unexamined and repeated. (Edmondson, 2018; Edmondson, 2023). Training students in the science of failing well is a powerful metacognitive dimension of the learning process itself and of the TAS pedagogy specifically. It is a skill they will bring to every element of their lives.

Thus, when an entire class failed a quiz in a literature class, the TAS instructor asked each team to discuss what had gone wrong for its members and what they would need to do to prevent it happening again. What breakthroughs could be created from this breakdown? The teams then presented their ideas to the class. In some cases, a long-standing issue of time management was finally being confronted. In others, a student realized they could have reached out to family members for childcare help.

The opportunities to bring the language of breakdown as the path to breakthrough into the classroom are endless. In some of the most moving essays in TAS classes, students wrote about important breakdowns in their life trajectories they had turned into breakthroughs (hanging out with ‘bad’ crowds, poor attendance, attitude issues, COVID, substance abuse). Assignments that ask students to reflect on how breakdowns can lead to breakthroughs in their lives help them learn this key vocabulary. At the same time, when reviewing an essay with serious punctuation errors, a professor pointed out to the student that they were having a breakdown with respect to the use of the period! The implication was clear: identify where and why this was happening and the actions needed to create a breakthrough in the troublesome but critical area of punctuation!

Perhaps the best definition of breakdown came from another student, who explained to the class that every breakdown was simply a learning opportunity.

Student Surveys: The Impact of Tas

The City University of New York (CUNY) serves a diverse but also vulnerable population that was hit especially hard by the pandemic (Abdrasheva et al., 2022; Aucejo et al., 2020; Ewing, 2021; Neuwirth et al., 2020). Our surveys show that TAS helps break the isolation still severely affecting many students. It provides assistance to the most vulnerable students, students with work and family responsibilities, and creates a sense of belonging and community for the online student. It is an aid in retention, course engagement and academic success while training students in the collaborative, leadership and teamwork skills they will need when they join the workforce. It has proven effective in European as well as US settings, across class divides, in both undergraduate and graduate settings and in science, engineering, technology and mathematics (STEM), humanities and vocational courses across the curriculum. See Appendix C for details and discussion of student surveys with illustrative graphs.

Teacher and Student Experiences

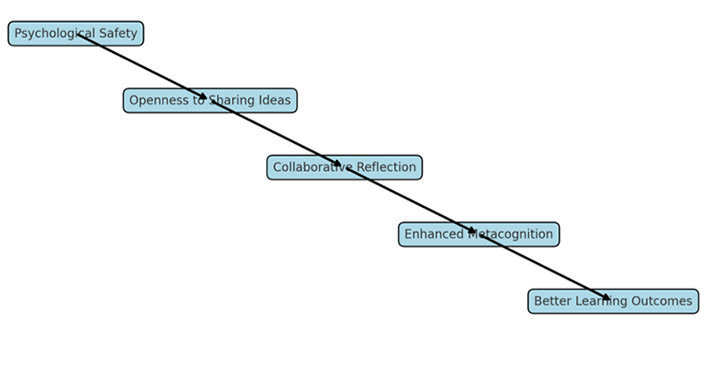

Psychological safety within student teams changes the nature of conversation and of thinking itself. There is a direct connection between the development of critical thinking and psychological safety, as the work of Lev Vygotsky and higher education studies cited earlier on the impact of fear on cognition make abundantly, if indirectly, clear (Dewey, 1916; Vygotsky, 1978). Figure 1 illustrates the progress illustrates the progression we see in many students from psychological safety to better learning outcomes.

Figure 1

Flowchart: Psychological Safety to Better Learning Outcomes

Source: authors’ own work.

Over a period of eight years of implementation, we found that student preparation, completion of assignments, grades and retention were improved with TAS. Course satisfaction was first on the list of student comments on their TAS classes (fun was the word most often used). Most moving was the pride and initiative that students took in making a difference in the lives of their teammates. In one case, a student reported that because she was required to support her team, she called her teammate every morning of class at 6 am. Otherwise, she said, he’d never make it to class on time. In another class, an autistic student credited his team’s support when he started turning in assignments and coming to class on time! The role of the intense peer support structure of TAS has been dramatic for the struggling student, the student with learning disabilities and for students juggling work and family responsibilities.

Practical Challenges

In one of our classes, an instructor new to TAS implemented her version for the duration of one project only and was disappointed not to see the results she was expecting. This pedagogy is about the directed relationship building of psychological safety over the two or three months of a semester and not for the week or two of a single project. The true magic of the program depends on the real-time building of psychological safety within student teams over the course of a semester. It requires educating the student regarding the point and purpose of TAS (reading, class discussion). This teacher was inspired by TAS, but the crucial underpinning of a full semester to build a strong foundation of psychological safety had either not been made clear to her or was discounted by the teacher. Would this instructor have been open to mentoring or video meetings to support her implementation of TAS? We look forward to using the possibilities created by online video platforms to bring training workshops to faculty everywhere. As our cohort of well-trained faculty grows, we will be able to bring mentoring to faculty requesting that support, as well.

TAS is not a teaching style or fit for every instructor. We acknowledge the individuality of teacher choices and practices and that this modality involves a commitment of additional time on the part of the instructor. For some, this will not be an appropriate procedure. For us and for many others, the gratifications are worth the cost in time and in effort. Indeed, TAS requires divided attention on the part of the instructor as they have to monitor and encourage the team bonding that underlies psychological safety on top of delivery of course materials. Ideally, the program would have institutional support so that the instructor was guided and compensated for the additional time and effort the pedagogy does require. At Kingsborough, TAS faculty were designated a Faculty Interest Group by the Center for Teaching and Learning for several years, and were awarded a Teaching Excellence Award which distributed release time credits to several of our TAS instructors. At the university level, the CUNY Research Foundation provided several larger grants to support faculty research, writing, and, more recently, the analysis of a larger set of TAS and control data.

Educating students to redirect habits of focusing on themselves and their grades to caring about and taking initiatives on behalf of teammates is another challenge not to be overlooked. While not all teams are equal in the levels of support they create and extend across a semester, much will depend on student understanding of the point of the TAS design of their class of their class and whether they commit. The Outgoing Team Leader Report makes it clear to the student that their performance in support of other students on their team counts and is recognized. The syllabus must articulate how teamwork will count towards the final grade. Where possible, student initiatives and interventions undertaken by the students on behalf of one another should be acknowledged privately and, where appropriate, publicly. At the same time, the directive to support others on their team has been meaningful and even exciting to many of our students. In one case, a student who was Team Leader told his team he would take the student who got the highest grade on an essay out to lunch. He did exactly that, to the delight of a student who happened to live in a desperately poor and violent neighborhood and who had almost never been to a restaurant. The Team Leader knew his teammates’ neighborhood, having barely escaped gunfire aimed at him in that neighborhood. The outing was a highlight of his experience that semester.

When we impact others, we experience our own power in the universe. The student who recounted this event was certain that his teammate finished the course successfully only because of the kindness and support he and his team had extended. Small acts of kindness ripple outward in small and big ways. In the classroom, they make possible the vulnerability that Brene Brown, in books like Daring Greatly and The Gifts of Imperfection, considers vital for deeper learning (Brown, 2010; Brown, 2012). This is the gift of TAS.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Some will argue that assertions made in this paper rely on research in other fields. Research in higher education however, has consistently demonstrated the benefits of collaborative learning and the detrimental effects of fear on cognition, growth, mental health and academic achievement. Team As Support (TAS) brings the specific vocabulary and focus on psychological safety to the field of higher education, leveraging these supporting studies to address this underexplored but critical element of the learning environment. Importantly, it also addresses complaints that are common in group work and which we, too, experienced before TAS when implementing a mix of TBL and TMLP in our classes. When instructors’ instructions given to students shifted from a focus on themselves and their grades to a focus on supporting their teammates, the improvement in team functioning and student satisfaction was huge.

This paper is part of a larger effort to fill a gap and promote TAS: in print, in presentations, at conferences, on a website with teaching materials we have now created, and in a full-length book that will be published as an Open Educational Resource publication. Our website (https://teamassupport.commons.gc.cuny.edu) features detailed teaching materials for the instructor and for students. Case studies, testimonials and video material from conference presentations will also be included.

Although not a substitute for objective data, student self-reported surveys cited in this study (Appendix) are not to be dismissed. They reflect the experiences of our students and are supported by teacher experiences over an eight-year period and by student reflective writing and comments, some included in this paper. At the same time, larger data sets are in the process of being analyzed. We look forward to the objective data collection and longitudinal studies that will replicate, deepen and extend our findings while clarifying long-term benefits and pitfalls.

TAS provides a form of 24/7 student-driven support that even the best resourced institution cannot replicate. The support made possible for the struggling, shy, disabled or otherwise disadvantaged student cannot be overestimated. While Kingsborough and Medger Evers would come under the heading of under-resourced colleges, our TAS classes at graduate and undergraduate levels at European institutions suggest that this pedagogy is transferable to multiple levels and contexts.

TAS is an innovative teaching modality based on a broad, multidisciplinary foundation that psychological safety is central to performance. Grounded in the most up-to-date theories of collaborative learning and studies of the impact of fear on cognition itself, TAS fills a crucial gap in higher education studies by transferring the insights and findings on psychological safety from medicine, psychology, trauma studies, business, leadership, management and more to higher education. TAS was, in the words of one of our faculty quoted earlier, a lifesaver during the pandemic. It is a lifesaver for the struggling student and for students in under - resourced institutions, and life-changing for students everywhere. It has inspired our faculty at Kingsborough, at Medger Evers and across the seas in Austria.

What if this Kingsborough-inspired pedagogy, TAS: Team as Support were to become a national or global model? How would this impact student lives and even the political fabric of our communities and countries? Students who learn to extend trust and build relationships within small, diverse teams are building meaningful connections outside the frameworks that have defined their lives. We are eager to bring this pedagogy to more instructors, students and classes across the nation and around the world.

Words like kindness and generosity are not words that many of us who teach in classrooms across the academy are used to hearing, but they are vital. They are lifelines to success, to happiness, to the achievement of dreams, to a better workforce and to an energized and more inclusive citizenry as well as to a more forgiving and less fractured society. Certainly, our role as instructor is nurturing these values in our students with the TAS pedagogy. Perhaps this excerpt from Naomi Shahib Nye’s poem Kindness (https://poets.org/poem/kindness) expresses the central and universal profundity of this very common word best:

Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

Then it is only kindness that makes any sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes ,br>

and sends you out into the day to mail letters and purchase bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking for,

and then goes with you everywhere like a shadow or a friend.

For webinar training, information and inquiries, email: leafridman120@gmail.com

References

- Abdrasheva, D., Escribens, M., Sabzalieva, E., Nascimento, D., & Yerov, C. (2022). Resuming or reforming? Tracking the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on higher education after two years of disruption. UNESCO. https://doi.org/10.54675/CCSH3589

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2019, September 7). Culture of safety. PSNet. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/culture-safety

- Aronson, B. (2020). HumanKind: Changing the world, one small act at a time. Life Tree Media.

- Aucejo, E. M., French, J., Ugalde Araya, M. P., & Zafar, B. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104271

- Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Harvard University Press.

- Baskin, K. (2023, June 14). Four steps to building the psychological safety that high-performing teams need today. Forbes India. https://www.forbesindia.com/article/harvard-business-school/four-steps-to-building-the-psychological-safety-that-highperforming-teams-need-today/86989/1

- Bellows, K. H. (2022, March 11). Katie Meyer’s suicide put the spotlight on student discipline. Experts say mental health is the larger issue. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/katie-meyers-suicide-put-the-spotlight-on-student-discipline-experts-say-mental-health-is-the-larger-issue

- Bransford, J., Donovan, S. M., & Pellegrino, W. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school (Expanded edition). National Academy Press.

- Brookfield, S. D. (1987). Developing critical thinkers: Challenging adults to explore alternative ways of thinking and acting. Jossey-Bass.

- Brookfield, S. D. (2012). Teaching for critical thinking: Tools and techniques to help students question their assumptions. Jossey-Bass.

- Brown, B. (2010). The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are. Hazelden.

- Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Penguin Publishing Group.

- Buettner, D. (2012). The Blue Zones: 9 lessons for living longer from the people who’ve lived the longest (2nd ed.). National Geographic.

- Carmeli, A., & Gittell, J. H. (2009). High-quality relationships, psychological safety and learning from failures in work organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(6), 709-729. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.565

- Clark, T. (2020, April 8). The four stages of psychological safety. Porchlight. https://www.porchlightbooks.com/blog/changethis/2020/the-four-stages-of-psychological-safety

- Cohn-Vargas, B., & Steele, D. M. (2013). Identity safe classrooms: Places to belong and learn. Corwin Press.

- Davidson, C. N., & Katopodis, C. (2022). The new college classroom. Harvard University Press.

- Dempsey, K. (n.d.). How psychological safety at work can affect mental health. Retrieved January 30, 2025, from https://theawarenesscentre.com/how-psychological-safety-at-work-can-affect-mental-health/

- Denial, C. J. (2024). A pedagogy of kindness. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Deutsch, M. (1949). A theory of cooperation and competition. Human Relations, 2(2), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872674900200204

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. Macmillan.

- Duhigg, C. (2016a). Smarter, faster, better: The transformative power of real productivity. Random House.

- Duhigg, C. (2016b, February 25). What Google learned from its quest to build the perfect team. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html

- Dweck, C. S. (2007). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Ballantine Books.

- Edmondson, A. C. (1996). Learning from mistakes is easier said than done: group and organizational influences on the detection and correction of human error. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 32(1), 5-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886396321001

- Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. (2018). The fearless organization: creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation and growth. Wiley & Sons.

- Edmondson, A. C. & Shike, L. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 23-43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

- Edmondson, A. (2023, July 28). It’s OK to fail but you have to do it right. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2023/07/its-ok-to-fail-but-you-have-to-do-it-right?registration=success

- Elizade-Utnick, G. (n.d.). Team-Based Learning (TBL) Faculty Development Open Educational Resource (OER). Retrieved January 30, 2025, from https://libguides.brooklyn.cuny.edu/tbloer/home

- Ewing, L. A. (2021). Rethinking higher education post COVID-19. In J. Lee, & S. H. Han (Eds.), The Future of Service Post-COVID-19 Pandemic. Volume 1. Rapid adoption of digital service technology (pp. 37-54). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4126-5_3

- Fiechtner, S. B., & Davis, E. A. (1985). Why some groups fail: A survey of students’ experiences with learning groups. Organizational Behavior Teaching Review, 9(4), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/105256298400900409

- Gallo, A. (2023, February 15). What is psychological safety? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2023/02/what-is-psychological-safety

- George, S. D., & Strauss, V. (2022, December 5). The crisis of student mental health is much vaster than we realize. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/12/05/crisis-student-mental-health-is-much-vaster-than-we-realize/

- Gorny-Wegrzyn, E., Perry, B., Stanton, C., Janzen, K. J., & Hack, R. (2022). Pedagogy of kindness: Changing lives, changing the world. Generics Publishing.

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books.

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1989). Cooperation and competition: Theory and research. Interaction Book Company.

- King, P. M., & Kitchener, K. S. (1994). Developing reflective judgment: understanding and promoting intellectual growth and critical thinking in adolescents and adults. Jossey-Bass.

- King, P. M., & Kitchener, K. S. (2002). The reflective judgment model: twenty years of research on epistemic cognition. In B. K. Hofer & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Personal epistemology: the psychology of beliefs about knowledge and knowing (pp. 37–61). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kish-Gephart, J. J., Detert, J. R., Trevino, L. K., & Edmondson, A. C. (2009). Silenced by fear: The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 163-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2009.07.002

- LaBeouf, J. P., Griffith, J. C., & Roberts, D. L. (2016). Faculty and student issues with group work: what is problematic with college group assignments and why? Journal of Education and Human Development, 5(1).

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- LeDoux, J. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 23, 155-184. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155

- LeGassick, G., Zaffron, S., Scheaf, L., Spirtos, M, Wright, J., & Elliott, C. (2011). Conversations that matter: Insights and distinctions - landmark essays. Vol 2. Landmark Worldwide.

- Lory, H. (2022, September 30). Why psychological safety matters in class. Harvard Graduate School of Education. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/ideas/news/22/09/why-psychological-safety-matters-class

- Medina, J. (2008). Brain rules: 12 principles for surviving and thriving at work, home and school. Pear Press.

- Michaelsen, L. K, Knight, A. B., L., & Fink, L. D. (Eds). (2004). Team-based learning: a transformative use of small groups in college teaching. Sterling.

- Michaelsen, L. K., & Sweet, M. (2008). The essential elements of team-based learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 116, 7-27. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.330

- Murthy, V. H. (2023). Together: The healing power of human connection in a sometimes lonely world. Harper Wave.

- Neuwirth, L. S., Jović, S., & Mukherji, B. R. (2020). Reimagining higher education during and post-COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 27(2), 141-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477971420947738

- Newman, A., Donnahue, R., & Nathan, E. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001

- Oakley, B., Felder, R. M., Brent, R., & Elhajj, I. (2004). Turning student groups into effective teams. Journal of Student-Centered Learning, 2(1), 9-34. https://engr.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/drive/1ofGhdOciEwloA2zofffqkr7jG3SeKRq3/2004-Oakley-paper(JSCL).pdf

- Perna, L. (Ed.). (2010). Understanding the working college student. New research and its implications for policy and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003448495

- Perna, L., & Odle, T. K. (2020). Recognizing the reality of working college students. Akademe, 106(1), 18-22.

- Piaget, J. (1970). Science of education and the psychology of the child. Orion Press.

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. Norton.

- Roberts-Grmela, J. (2023, June 5). More students want virtual-learning options. here’s where the debate stands. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/more-students-want-virtual-learning-options-heres-where-the-debate-stands

- Shagholi, R., Hussin, S., Siraj, S., Naimie, Z., Assadzadeh, F., & Moayedi, F. (2010). Value creation through trust, decision making and teamwork in educational environment. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 255-259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.007

- Sibley, J., Ostafichuk, P., Roberson, B., Franchini, B., & Michaelsen, L. K. (2014). Getting started with team-based learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003445012

- Simons, A., & Almasy, N. (2019). Repurposing kindness: Using collaboration and kindness as a catalyst to aid success, prepare for practice. Convention. 375. https://www.sigmarepository.org/convention/2019/posters_2019/375

- Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: how stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613

- Taylor, A. (2011). Top 10 reasons students dislike working in small groups... and why I do it anyway. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 39(3), 219-220. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.20511

- Tulshyan, R. (2021, March 15). Why is it so hard to speak up at work? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/15/us/workplace-psychological-safety.html

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4

- Wanless, S. B. (2016). The role of psychological safety in human development. Research in Human Development, 13(1), 6-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1141283

- Zapolski, N., & DiMaggio, J. (2011). Conversations that matter: Insights and distinctions - landmark essays. Vol. 1. Landmark Worldwide.

- Zeffron, S., & Logan, D. (2011). The three laws of performance: rewriting the future of your organization and your life. Jossey-Bass.

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-7787-8165

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-7787-8165