Informacje o artykule

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em108.1693

W wersji drukowanej czasopisma artykuł znajduje się na s. 74-81.

Pobierz artykuł w wersji PDF

Pobierz artykuł w wersji PDF

Abstract in English

Abstract in English

Jak cytować

Lipowska, I. (2025). Effects of the Reference Price in the Context of the Extended Information Obligation under the Omnibus Directive – Seller’s Perspective. e-mentor, 1(108), 74-81. https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em108.1693

E-mentor nr 1 (108) / 2025

Spis treści artykułu

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The Role of the Reference Price in Communicating Price Promotions

- Expansion of Terminology Related to the Reference Price

- Regular Price vs Promotional Price vs Omnibus Price – Reference Price Effect Scenarios

- Summary

- References

Informacje o autorze

Przypisy

1 For ease of reading, any reference to the directive is a reference to the Omnibus Directive, while the lowest price applied over the 30-day period preceding the price reduction is referred to in this article as the omnibus price.

2 In a statement, the President of UOKiK (2023) remarked: “Price transparency in the case of promotions provides consumers with a real reference point when making purchasing decisions. With clear and reliable information about the price, unit price, and the lowest price over the last 30 days, consumers will know whether the offer from a given business is truly advantageous. Consumers, knowing the lowest price over the 30-day period, will no longer be misled by false discounts resulting solely from unfair business practices”.

3 This obligation is provided for in the Directive on consumer protection in the indication of the prices of products offered to consumers indicated in the introduction to this article as part of the Omnibus Directive.

Effects of the Reference Price in the Context of the Extended Information Obligation under the Omnibus Directive – Seller’s Perspective

Ilona Lipowska

Abstract

This article aims to describe the impact of the information obligation provided for in the Omnibus Directive on how sellers provide information concerning prices. The theoretical objective is to expand the terminology related to the concept of the reference price. The reference price effects are assessed from the seller's perspective, who has a real influence on the price level communicated to consumers.

This article is a theoretical study based on the issue of the reference price, derived from the field of behavioural economics. The main part of this article introduces an original proposal for expanding the terminology regarding the concept of the reference price—specifically, the introduction of a primary and secondary reference price. Additionally, three reference price effect scenarios (positive, negative, and neutral) are presented, occurring depending on the bilateral relationship between the promotional price, the mandatory omnibus price, and the voluntary regular price. Sellers are undoubtedly aware of the significance of the reference price in shaping a positive perception of prices and recognise the significant limitations arising from the implementation of the Omnibus Directive into national legislation in this regard. The extension of the information obligation when announcing price reductions has generated new reference prices communicated to customers. To achieve the guaranteed positive reference price effect, two reference prices (primary and secondary) are sometimes used.

Keywords: reference price, price communication, primary and secondary reference price, price promotions, Omnibus Directive

Introduction

As of 1 January, 2023, new regulations under the Omnibus Directive (European Parliament, 2019) came into force in Poland, strengthening consumer protection. The Omnibus Directive imposes a legal obligation on businesses to state the lowest price applied over the 30-day period prior to a price reduction when announcing a reduced (promotional) price. The Omnibus Directive amends four consumer protection directives, one of which is Directive 98/6/EC on consumer protection in the indication of the prices of products offered to consumers (European Parliament, 1998; EY Polska, 2022). These legislative changes are part of the New Deal for Consumers—an initiative aimed at strengthening EU consumer protection laws and modernising EU consumer protection regulations in response to market developments. The initiative was adopted by the European Commission on 11 April, 2018 (European Parliament, 2018).

These legislative developments reflect an effort to adapt existing rules to market conditions and the ongoing digitisation of the economy (EY Polska, 2022). The implementation of the directive into national law has resulted in new information obligations for businesses, and compliance with these obligations serves as confirmation of a given entity’s adherence to the law. Breach of the obligations resulting from implementation of the directive into national law may lead to companies being fined. Under the Omnibus Directive, Article 8b(1) was added to Directive 93/13/EEC (European Parliament, 2019), stating that the penalties for infringements of national provisions implementing the directive, as adopted by Member States, must be effective, proportionate, and dissuasive.

One of the key changes under the Omnibus Directive concerns the requirement for transparent price reduction information - sellers are now required to state the price of the product previously applied for a specified period1 when announcing a reduced (promotional) price. Under the Omnibus Directive, Article 6a(2) of Directive 98/6/EC clarifies that the “prior price means the lowest price applied by the trader during a period of time not shorter than 30 days prior to the application of the price reduction” (European Parliament, 2019).

The Omnibus Directive entered into force on 7 January, 2020. EU Member States were required to adopt the necessary implementing provisions by 28 November, 2021, and the implemented provisions, in accordance with the directive, were to be applied from 28 May, 2022. In Poland, as in several other Member States, the implementation of the directive was delayed (Czeladzka, 2022). Polish law was harmonised with the Omnibus Directive through an amendment to the Act on Price Information for Goods and Services (2014). Article 4(2) was revised to state: “Whenever a price reduction is announced for a product or service, alongside the information on the reduced price, information must also be displayed about the lowest price of that product or service that applied during the 30-day period prior to the reduction” (Act..., 2014). Furthermore, the amount of financial penalties for non-compliance with obligations under the directive is regulated by Article 6 of this act. Alongside the amendment to the act, the Regulation of the Minister of Development and Technology of 19 December, 2022 on the Display of Prices of Goods and Services (Journal of Laws of 2022, item 2776) entered into force on 1 January, 2023. This regulation includes, among other things, the obligation to display, alongside the price and unit price, information about the reduced price of a product or service (Regulation..., 2022).

Undoubtedly, the legislative changes were prompted by numerous unfair market practices. With regard to price communication, this involved artificially inflating prices to subsequently introduce vast discounts. This was a mechanism by which the regular price of PLN X would be increased to X+1 a few days before the ‘promotion’ so that on the day of the sale the ‘promotional price’ could be announced as PLN X. Such practices were successful due to consumers’ limited knowledge of prices — who had less knowledge than they believed (Kenning et al., 2007, p. 112; Loj et al., 2020; Mӓgi & Julander, 2005; Vanhuele & Drèze 2002; Vanhuele et al., 2006, p. 164). Early studies conducted by Zeithaml (1988) found that consumers’ knowledge of prices was significantly lower than necessary for them to have a precisely defined internal reference price for many products. It can be assumed that the 30 days defined in the Omnibus Directive was aimed precisely at eliminating such practices, which tend to intensify particularly when consumer shopping activity increases, on Black Friday, before Valentine’s Day, or during the holiday seasons2.

This article aims to describe the effect of the information obligation under the Omnibus Directive on price communication by sellers. The theoretical objective is to expand the terminology related to the concept of the reference price. The nature of the reference price effects is assessed from the seller's perspective , who has a real influence on the price level communicated to consumers. The nature of the reference price effect about shaping consumer behaviour has already been described in the literature (e.g., Martín-Herrán & Sigué, 2023), but the legal regulations resulting from the Directive on consumer protection on the indication of the prices of products offered to consumers (which is part of the Omnibus Directive) have led to renewed interest in the reference price.

This article adopts the seller’s perspective—when discussing the nature of the reference price effect (positive, negative, or neutral), the author refers to intangible benefits. A seller’s benefits may take an intangible (image-related) form and a tangible (financial) form—the first type may be obtained by skillfully managing the reference price(s), which ultimately may lead to achieving financial benefits of the second type. The reference in this article to benefits for the seller means the positive perception of price, thus shaping the perceived attractiveness of the price (Niedrich et al., 2001, p. 340). Price perception (evaluation of a price as high/unattractive or low/attractive) is the result of a comparison between the current price and the reference price (Oh, 2003, p. 387) and constitutes an important element of the overall price image of the retailer (store) (Hamilton & Chernev, 2013, p. 4). The price image of the retailer significantly determines consumers’ purchasing decisions, including the choice of retailer (store) (Srivastava & Lurie, 2001). Over the years, researchers have determined that price perception has a positive impact on consumer satisfaction (Voss et al., 1998) and that price perception is of even greater importance than product quality (Varki & Colgate, 2001, p. 233). Srikanjanarak et al. (2009, p. 79) emphasised both the indirect and direct impact of satisfaction resulting from price perception on customers’ decision-making. Price perception is equally a subject of psychology as it is of economics (Bolton et al., 2010, p. 564).

The first part of this article addresses the nature of the reference price and its relationship with price reduction communication. Next, the author makes a proposal for expanding the terminology related to the reference price, and the reference price effect scenarios that occur depending on the relationship between the promotional price, the mandatory Omnibus Price, and the voluntary regular price. In the final part, conclusions regarding the intended and unintended consequences of harmonising national laws with the Omnibus Directive guidelines are formulated. The author’s envisaged contribution of the article to the development of the discipline of management and quality sciences is the expansion of terminology related to the reference price and the update of the reference price concept in the context of current regulations, by identifying changes in price communication processes.

The Role of the Reference Price in Communicating Price Promotions

An important area of research on price as a marketing tool is the behavioural reaction of buyers to price (Kalyanaram & Winer, 2022, p. 46). Periodic discounts are one way to shape consumers’ positive attitudes toward a promoted offer by presenting them with an attractive price. Price promotions are a very popular form of sales promotion, consisting of short-term actions aimed at improving the perceived value of a promoted product to achieve relatively quick sales effects (Spyra, 2013). Sales promotion can take the form of price promotions and non-price promotions (Kwiecińska et al., 2014). A key characteristic that distinguishes it from other tools of market communication is the short duration of attractive purchase conditions (increased perceived value of the offer), intended to encourage consumers to make a purchasing decision. This promotional tool has a call-to-action nature, as it provides an incentive (call) that triggers a customer response (action) (Vafainia et al., 2019, p. 64). Unlike permanent price reductions, price promotions, as defined by the regulatory changes discussed in this article, are now subject to a new information obligation—that is, the requirement to state the lowest price within the last 30 days before the reduction, which serves as the reference price.

The concept of the reference price has a long history of application in marketing and consumer behaviour studies (Elshiewy & Peschel, 2022, p. 496). The existence of the reference price has been theoretically confirmed, primarily within the Adaptation Level Theory (Helson, 1964) and Prospect Theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). The Mental Accounting Theory (Thaler, 1985) is also frequently referenced in this context. Behavioural economics literature highlights the usefulness of the reference price in buyers’ decision-making (Anton et al., 2023, p. 104). According to Kahneman (2011, p. 373), a reference point is a prior state against which gains and losses are evaluated. In turn, the reference price is the price against which consumers compare the price of the product they are currently considering purchasing (Monroe, 1990). It represents a price standard shaped by previous price exposures (Monroe, 1973). Thaler (2018, p. 86) explained the concept of the reference price in the context of transaction utility, which reflects the consumer’s perception of an offer’s attractiveness. He defined transaction utility as the difference between the actual price paid and the reference price. Therefore, if the price of a given product is lower than the reference point, consumers perceive a gain, which encourages them to make a purchase. Conversely, if the product price is higher than the reference point, consumers perceive a loss, which discourages them from making a purchase (Anton et al., 2023; Lin, 2016).

Numerous academic studies have attempted to operationalise the concept of the reference price (Bolton et al., 2003; Bondos & Lipowski, 2022; Jacobson & Obermiller, 1990; Liu & Popkowski Leszczyc, 2023; Lowengart, 2002; Mazumdar et al., 2005; Mezias et al., 2002; Moon et al., 2006). However, this does not alter its role in price acceptance processes—that is, moderating consumer reactions to price (Rajendran, 2009) and, more broadly, influencing purchase intent, brand choice, the likelihood of product search, and price-related perceptions (Jindal, 2022). In the context of the information obligation introduced in the directive, the omnibus price serves as an external reference price, which is distinct from the internal reference price (Oest, 2013). The external reference price is shaped by market observations (e.g., prices seen in stores or online), whereas the internal reference price is based on prices remembered by consumers from previous shopping experiences and their internal beliefs about fair pricing (Wu et al., 2012).

An important factor determining the effectiveness of price communication is the decoding stage, in which a potential customer processes the price information conveyed to them. At this stage, the recipient must interpret the presented price in a way that aligns as closely as possible with the perception the sender intends to achieve (Bondos, 2014, p. 340). The core purpose of the reference price is to shape a positive perception of the product’s price, and as such, it is typically presented as higher than the current price. No rational seller would voluntarily disclose that a previous price (recently in effect) was lower than the current price. However, under the Omnibus Directive, which has been transposed into national law, this reference price (i.e., the lowest price in the last 30 days) must always be stated, regardless of its relation to the current product price. As a result, in some cases, a negative reference price effect is created—the current price after the reduction is higher than the lowest price recorded in the last 30 days. This effect is one of the intended goals behind the drafting of the Omnibus Directive—it represents greater transparency in communication with customers. The reference price is intended to facilitate the decision-making process (Qin & Liu, 2022).

Expansion of Terminology Related to the Reference Price

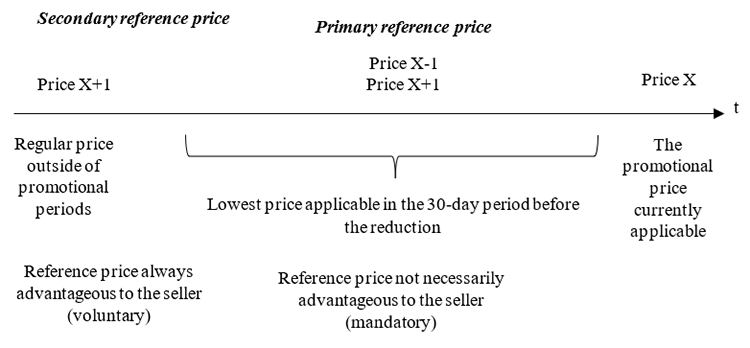

In an effort to mitigate the negative reference price effect resulting from regulatory changes following the implementation of the Omnibus Directive, retailers are expanding price communication strategies by introducing an additional (second) reference price. According to the author, since there are now two reference prices, it is advisable to distinguish between them by expanding the applied terminology. The author proposes using the terms primary and secondary reference price. The term primary reference price is used to mean the lowest price in the 30-day period preceding the price reduction, while the secondary reference price is the regular price before the discount. The second reference price corresponds to the product price before the discount period, i.e., the price that applied outside of discount periods, regardless of the duration of the price reduction. Due to its secondary role in the process of communicating price attractiveness, the author refers to it as the secondary reference price, in contrast to the primary reference price, which is the lowest price recorded in the 30-day period before the discount. The use of the adjectives primary and secondary also aligns with the legal obligation of price disclosure3—the primary reference price is mandatory, whereas the secondary reference price is optional. From the seller’s perspective, the secondary reference price is intended to shape a positive perception of the current (reduced) product price: the price today is X (e.g., PLN 59.90); although the lowest available price in the last 30 days was X-1 (PLN 29.90), the regular price before the discount period was X+1 (e.g., PLN 79.90). The concept of primary and secondary reference prices in the price communication process over time is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1

Secondary and Primary Reference Price Diagram

Source: author’s own work.

Regular Price vs Promotional Price vs Omnibus Price – Reference Price Effect Scenarios

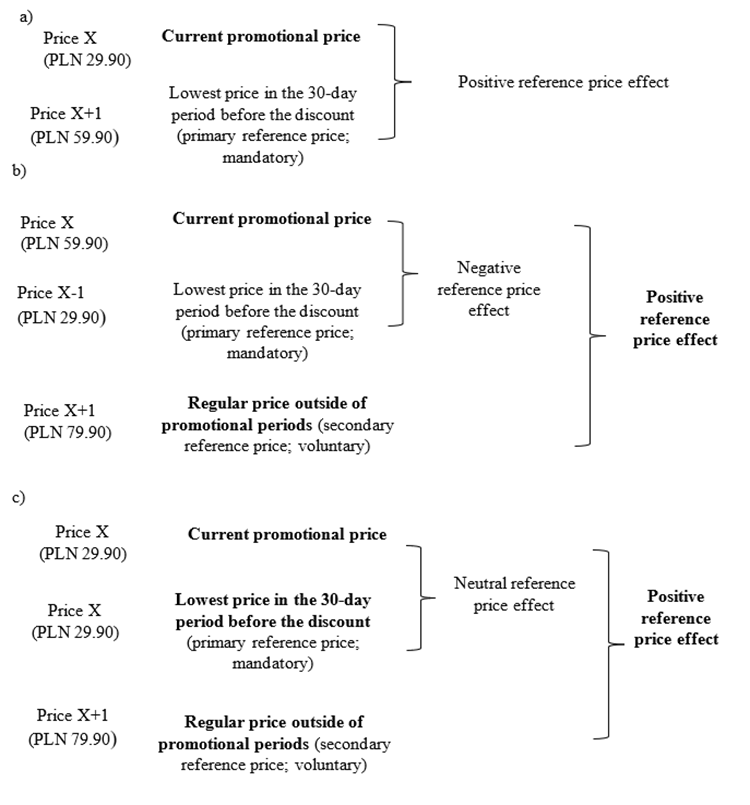

The nature of the three reference price effect scenarios , from the seller’s perspective, is described in figure 2. Scenario (a) occurs when the current promotional price is lower than the legally required price (the omnibus price, i.e., the lowest price applied within the 30-day period preceding the reduction). In this case, the effect of the reference price is positive because the comparison between the current promotional price and the Omnibus Price favours the former. In such a situation, there is no need to additionally present the secondary reference price, as the positive effect has already been achieved through the primary reference price. However, the current price is not always genuinely promotional in the long term, meaning that within the last 30 days, the price of the analysed product could have been even lower.

Scenario (b) occurs when the current promotional price is higher than the omnibus price. In this scenario, the reference price effect is negative (the comparison between the current promotional price and the Omnibus Price works to the disadvantage of the former). To mitigate this negative effect, the seller supplements the price communication with an additional (third) price—the regular price that applies outside of promotional periods (the secondary reference price). The objective is to create a positive reference price effect, where the comparison between the current promotional price and the price outside promotional periods favours the former. In some cases, achieving a positive reference price effect requires the voluntary presentation of a third price, i.e., the regular price outside promotional periods. Importantly, the Omnibus Directive does not apply to this price, meaning that the information about this price does not include information about a specific timeframe during which it was valid. In practice, this means that sellers can communicate this secondary reference price, which may have been in effect several weeks or even months beforehand. Since the regulations do not make this information mandatory, they also do not require the precise period when the regular price was in effect to be specified.

In the market, there is also a third possibility (figure 2, scenario c), which assumes that the reference price effect between the current promotional price and the lowest price in the last 30 days is neutral. In this case, the primary reference price does not ensure the desired positive reference price effect. To achieve this effect, sellers additionally state the secondary reference price—the regular price outside the promotional period. In such a situation, the secondary reference price is indispensable for creating a positive comparison effect.

Figure 2

Positive, Negative, and Neutral Reference Price Effect – Seller’s Perspective

Source: author’s own work.

A summary is provided, organising the scenarios described in figure 2 according to the criterion of benefits for the seller in shaping the price attractiveness of the offer, assuming that both the mandatory reference price (the primary reference price) and the voluntary reference price (the secondary reference price) are used (table 1).

Table 1Summary and Evaluation of Possible Reference Price Effects – Seller’s Perspective

| Scenario (as in Figure 2) |

Reference Price Effect Depending on the Type of Reference Price | Evaluation of the Effect from the Seller’s Perspective |

| a) | Reference price effect for the primary reference price only | positive |

| b) | Reference price effect for the primary reference price | negative |

| Reference price effect for the secondary reference price | positive | |

| c) | Reference price effect for the primary reference price | neutral |

| Reference price effect for the secondary reference price | positive |

Source: author’s own work.

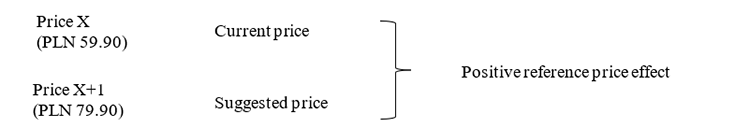

Another common practice for shaping the positive perception of a product’s current price is the communication by the retailer (intermediary) of the suggested price, understood as the price recommended by the manufacturer—a neutral suggestion regarding the price level, without imposing a specific price level. The seller must be guaranteed freedom in setting prices—they may, but are not obliged to, follow the manufacturer’s suggestion. In the process of market communication, the suggested price plays an extremely important role in shaping the positive perception of the current offer. The suggested price acts as a reference price for the current price (figure 3). If the seller does not present the product price as promotional, there is no obligation to disclose the lowest level in the last 30 days, and indicating the suggested price makes the offer more attractive. The suggested price is an example of the advertised reference price (ARP), in contrast to the unadvertised reference prices (Jensen et al., 2003; Jindal, 2022).

Figure 3

Positive Reference Price Effect if the Suggested Price is Communicated

Source: author’s own work.

What is important is that the suggested price can be used in the process of shaping the price attractiveness of an offer independently of the Omnibus Directive implemented into national legislation, as the directive applies specifically to the communication of price promotions. The suggested price generates a positive reference price effect without the need to reduce the current price. Thus, the current price, not being a promotional price, does not need to be accompanied by information about the Omnibus Price (thereby eliminating the risk of a negative reference price effect) and can instead be accompanied by the suggested price, which ensures a positive reference price effect.

Summary

In the initial weeks following the implementation of the new regulations under the Omnibus Directive, the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection (UOKiK) conducted inspections and identified numerous irregularities in the communication of the omnibus price during price promotions (UOKiK, 2023). Importantly, most of the errors were related to the nature of the reference price—the goal of improper (unclear) communication of the promotional price was to minimise the negative comparison effect. Understanding this effect is crucial for the effective shaping of positive price perception. Sellers are undoubtedly aware of the importance of the reference price in shaping positive price perception and, since January 2023, have recognised significant limitations under the Omnibus Directive in this regard.

However, as market practice demonstrates, sellers are striving to eliminate the negative reference price effect associated with the primary reference price by shaping a positive effect using the secondary reference price. Thus, the intended outcome for sellers is a positive reference price effect—achieved either in a two-price system (promotional and omnibus prices) or only in a three-price system (in which the regular price is included). In this context, a topic worthy of further exploration would be determining the differences in the influence of the various coexisting reference price effects.

References

- Act on Price Information for Goods and Services. (2014). [Ustawa z dnia 9 maja 2014 r. o informowaniu o cenach towarów i usług (Dz. U. 2023, poz. 168)]. https://sip.lex.pl/akty-prawne/dzu-dziennik-ustaw/informowanie-o-cenach-towarow-i-uslug-18109812

- Anton, R., Chenavaz, R. Y., & Paraschiv, C. (2023). Dynamic pricing, reference price, and price-quality relationship. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 146, 104586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2022.104586

- Bolton, L. E., Keh, H. T., & Alba, J. W. (2010). How do price fairness perceptions differ across culture? Journal of Marketing Research, 47(3), 564–576. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.47.3.564

- Bolton, L. E., Warlop, L., & Alba, J. W. (2003). Consumer perceptions of price (un)fairness. Journal Of Consumer Research, 29(4), 474–491. https://doi.org/10.1086/346244

- Bondos, I. (2014). Komunikacyjna rola ceny w procesie docierania z informacją do klienta [Communication role of price in the process of reaching out with the information to the customer]. Marketing i Rynek, 8(CD), 338–343.

- Bondos, I., & Lipowski, M. (2022). Consequences of the new reference price for multi-channel retailers after lockdown due to SARS-CoV-2. Marketing i Rynek, 2, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.33226/1231-7853.2022.2.3

- Czeladzka, M. (2022). Dyrektywa Omnibus – obowiązek informowania o cenach. PARP. https://www.parp.gov.pl/component/content/article/82715:dyrektywa-omnibus-obowiazek-informowania-o-cenach;#_ftn1

- Elshiewy, O., & Peschel, A. O. (2022). Internal reference price response across store formats. Journal of Retailing, 98(3), 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2021.11.001

- European Parliament. (1998). Directive 98/6/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 1998 on consumer protection in the indication of the prices of products offered to consumers. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A31998L0006

- European Parliament. (2018). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee a New Deal for Consumers. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2018:183:FIN

- European Parliament. (2019). Directive (EU) 2019/2161 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 amending Council Directive 93/13/EEC and Directives 98/6/EC, 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the better enforcement and modernisation of Union consumer protection rules (Text with EEA relevance).https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019L2161

- EY Polska. (2022). Dyrektywa Omnibus – nowe narzędzie do zwiększenia ochrony konsumentów w UE. https://www.ey.com/pl_pl/law/dyrektywa-omnibus-nowe-narzedzie-do-ochrony-konsumentow

- Hamilton, R., & Chernev, A. (2013). Low prices are just the beginning: Price image in retail management. Journal of Marketing, 77(6), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.08.0204

- Helson, H. (1964). Adaptation-level theory: an experimental and systematic approach to behavior. Harper and Row.

- Jacobson, R., & Obermiller, C. (1990). The formation of expected future price: A reference price for forward-looking consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(4), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1086/209227

- Jensen, T., Kees, J., Burton, S., & Turnipseed, F. L. (2003). Advertised reference prices in an Internet environment: Effects on consumer price perceptions and channel search intentions. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 17(2), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.10052

- Jindal, P. (2022). Perceived versus negotiated discounts: The role of advertised reference prices in price negotiations. Journal of Marketing Research, 59(3), 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222437211034443

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Pułapki myślenia. O myśleniu szybkim i wolnym. Media Rodzina.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

- Kalyanaram, G., & Winer, R. S. (2022). Behavioral response to price: Data-based insights and future research for retailing. Journal of Retailing, 98(1), 46–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2022.02.009

- Kenning, P., Evanschitzky, H., Vogel, V., & Ahlert, D. (2007). Consumer price knowledge in the market for apparel. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 35(2), 97–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550710728075

- Kwiecińska, A., Kraus, M., & Kroenke, M. (2014). Jak się robi promocje cenowe. Marketing w Praktyce, 7. https://marketing.org.pl/mwp/376-jak-sie-robi-promocje-cenowe

- Lin, Z. (2016). Price promotion with reference price effects in supply chain. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 85, 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2015.11.002

- Liu, X., & Popkowski Leszczyc, P. T. L. (2023). The reference price effect of historical price lists in online auctions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 71, 103183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103183

- Loj, J.-P., Ceynowa, C., & Kuhn, L. (2020). Price recall: Brand and store type differences. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53, 101990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101990

- Lowengart, O. (2002). Reference price conceptualisations: An integrative framework of analysis. Journal of Marketing Management, 18(1–2), 145–171. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257022775972

- Martín-Herrán, G., & Sigué, S. P. (2023). An integrative framework of cooperative advertising with reference price effects. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 70, 103166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103166

- Mazumdar, T., Raj, S. P., & Sinha, I. (2005). Reference price research: Review and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 69(4), 84–102. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.84

- Mӓgi, A.W., & Julander, C.-R. (2005). Consumers’ store-level price knowledge: Why are some consumers more knowledgeable than others? Journal of Retailing, 81(4), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2005.02.001

- Mezias, S. J., Chen, Y.-R., & Murphy, P. R. (2002). Aspiration-level adaptation in an american financial services organization: A field study. Management Science, 48(10), 1285–1300. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.48.10.1285.277

- Monroe, K. B. (1973). Buyers' subjective perceptions of price. Journal of Marketing Research, 10(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/3149411

- Monroe, K. B. (1990). Pricing: Making profitable decisions. McGraw-Hill.

- Moon, S., Russel, G. J., & Duvvuri, S. D. (2006). Profiling the reference price consumer. Journal of Retailing, 82(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2005.11.006

- Niedrich, R. W., Sharma, S., & Wedell, D. H. (2001). Reference price and price perceptions: A comparison of alternative models. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(3), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1086/323726

- Oest, R., van (2013). Why are consumers less loss averse in internal than external reference prices? Journal of Retailing, 89(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2012.08.003

- Oh, H. (2003). Price fairness and its asymmetric effects on overall price, quality, and value judgments: the case of an upscale hotel. Tourism Management, 24(4), 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00109-7

- Qin, Ch.-X., & Liu, Z. (2022). Reference price effect of partially similar online products in the consideration stage. Journal of Business Research, 152, 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.06.043

- Rajendran, K. N. (2009). Is reference price a fair price or an expected price? Innovative Marketing, 5(2), 18–29.

- Regulation of the Minister of Development and Technology of 19 December, 2022 on the Display of Prices of Goods and Services (2022). [Rozporządzenie Ministra Rozwoju i Technologii z dnia 19 grudnia 2022 r. w sprawie uwidaczniania cen towarów i usług (Dz. U. 2022, poz. 2776)]. https://sip.lex.pl/akty-prawne/dzu-dziennik-ustaw/uwidacznianie-cen-towarow-i-uslug-21770254

- Spyra, Z. (2013). Programy lojalnościowe wielkich sieci handlowych jako narzędzie komunikacji marketingowej – ewolucja i uwarunkowania sukcesu rynkowego. Studia Ekonomiczne. Zeszyty Naukowe Wydziałowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach, 140, https://www.ue.katowice.pl/fileadmin/_migrated/content_uploads/4_Z.Spyra_Programy_lojalnosciowe_wielkich_sieci_handlowych.pdf

- Srikanjanarak, S., Omar, A., & Ramayah, T. (2009). The conceptualisation and operational measurement of price fairness perception in mass service context. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 14(2), 79–93.

- Srivastava, J., & Lurie, N. (2001). A consumer perspective on price‐matching refund policies: Effect on price perceptions and search behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(2), 296–307. https://doi.org/10.1086/322904

- Thaler, R. H. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.4.3.199

- Thaler, R. H. (2018). Zachowania niepoprawne. Tworzenie ekonomii behawioralnej. Media Rodzina.

- UOKiK. (2023). Prawa Konsumenta 2023 – Prezes UOKiK mówi „sprawdzam". Urząd Ochrony Konkurencji i Konsumentów. https://uokik.gov.pl/aktualnosci.php?news_id=19234

- Vafainia, S., Breugelmans, E., & Bijmolt, T. (2019). Calling customers to take action: The impact of incentive and customer characteristics on direct mailing effectiveness. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 45(1), 62–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2018.11.003

- Vanhuele, M., & Drèze, X. (2002). Measuring the price knowledge shoppers bring to the store. Journal of Marketing, 66(4), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.66.4.72.18516

- Vanhuele, M., Laurent, G., & Drèze, X. (2006). Consumers’ immediate memory for prices. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1086/506297

- Varki, S., & Colgate, M. (2001). The role of price perceptions in an integrated model of behavioral intentions. Journal of Service Research, 3(3), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467050133004

- Voss, G. B., Parasuraman, A., & Grewal, D. (1998). The roles of price, performance, and expectations in determining satisfaction in service exchanges. Journal of Marketing, 62(4), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299806200404

- Wu, Ch.-Ch., Liu, Y.-F., Chen, Y.-J, & Wang, Ch.-J. (2012). Consumer responses to price discrimination: Discriminating bases, inequality status, and information disclosure timing influences. Journal of Business Research, 65(1), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.02.005

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251446

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9759-8517

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9759-8517