About the article

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em110.1712

The article is in the printed version on pages 21-31.

Download the article in PDF version

Download the article in PDF version

How to cite

Moczulska, M., & Spodarczyk, E. (2025). The actions of a university that is accountable towards internal stakeholders. The perspective of academics. e-mentor, 3(110), 21-31. https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em110.1712

E-mentor number 3 (110) / 2025

Table of contents

About the authors

Footnotes

1 Carried out March 13th, 2023

2 Academics in Poland are evaluated on the basis of their publications. At the same time, the evaluation criterion is the value of the journal expressed in points and determined by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

The Actions of a University that is Accountable Towards Internal Stakeholders. The Perspective of Academics

Marta Moczulska, Edyta Spodarczyk

Abstract

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a concept that can be applied by both businesses and not-for-profit organizations. Universities inform students about CSR and conduct research on CSR, and some universities themselves introduce a social responsibility (SR) strategy. Employees are an important group of University Social Responsibility (USR) stakeholders. Few studies on USR with regard to employees are available. The aim of this article is to determine the specific nature of the social responsibility of universities toward academics, and this goal was achieved in two stages. The first stage was a systematic literature review, and the second stage was a qualitative study conducted through in-depth group interviews with employees of two universities. The results of the study were used to determine the pillars of the university's social responsibility towards academics. Suggestions were also made for the process of developing the university's social responsibility strategy towards employees. In closing, this article specifies the premises for further research in this area.

Keywords: CSR, USR, stakeholders, internal stakeholders, academics

Introduction

Interest in SR stems primarily from its ability to solve economic, social and environmental problems, thereby fostering benefits for society at large. Many publications (Drobny, 2016; Gałat, 2018, Marinescu et al., 2010; Markus & Govender, 2023; Szelągowska-Rudzka, 2018) emphasize the role of universities in shaping social responsibility, expanding knowledge about it and thus making changes. For this reason, opportunities for SR measures to be taken at the university were identified (Cichowicz & Nowak, 2018; Karwowska & Leja, 2018; Mackiewicz et al., 2018; Merta-Staszczak et al., 2020). As lecturers, employees can expand students' awareness of SR and of research to contribute to society (see Kędzierska, 2018; Kowalska, 2009; Ławicka, 2016; Piasecka, 2015). This is the subject of much research (Burcea & Marinescu, 2011; Cichorzewska, 2015; Pabian, 2019). On the other hand, as employees, they are beneficiaries of SR activities. However, this issue is not broadly analyzed.

The above led the authors to analyze URS in terms of the university-employee relationship, with the goal of determining the form taken by SR of universities towards academics.

Theoretical Background

In order to establish current USR best practices, a systematic review of the literature was conducted 11. The process proposed by Denyer and Tranfield (2009) was followed, incorporating Hensel's (2020) guidance on the implementation of specific activities, and based on the EBSCO multi-search engine. The terms adopted were university social responsibility, employee, academic, scientists or researchers, and internal stakeholders. In each search, the first of the phrases was included in the title of the publication (as the main issue). The search was then restricted according to the inclusion criteria, i.e., peer-reviewed scientific articles, no time limitation, and publication language (Polish, English). The exclusion criteria were books, conference materials, newspaper articles and lack of access to the content of publications (books, conference materials, press articles and lack of access to the content of publications). In the next stage, recurring works were removed, and 31 hits were obtained. The obtained matching items were reviewed based on their compatibility with the issue under analysis, i.e. how SR is implemented at a university. Articles in which SR was only a context for the main issues presented (e.g., library development, improvement of students) were rejected. Fifteen articles were deemed suitable for analysis (for details, see appendix 1, table 1).

Due to the Polish research context, an additional search was conducted in the CEJSH and BazEkon databases. Although 19 articles were identified, only nine were included in the analysis (see appendix 1, table 2). Theoretical articles predominated (five). The results of the analysis were presented by showing the specifics of the social responsibility of the university concerned (for business) and the directions of considerations.

The Esfijani team (after Pabian, 2019, p. 105) considers social responsibility of the university: “a concept whereby a university integrates all of its functions and activities with the needs of society through active engagement with its communities in an ethical and transparent manner which aims to meet the expectations of all stakeholders”. Tetřevová and Sabolová (Pabian, 2019) in turn have identified five levels of USR: economic, ethical, sub-social, philanthropic and environmental. The first is related to stakeholder relations, transparency and the quality and security of services offered. The second refers to the ethicality of the actions taken, including protection of intellectual property and respect for copyright. The sub-social level relates to hiring policies, enhancing skills and training, taking care of health and safety, work-life balance, ensuring equality in the workplace, recruiting minorities and observing human rights. The philanthropic level refers to philanthropic activities and volunteerism. The last level is the protection of natural resources, investing in the development of environmental technologies, and preserving services favorable to the environment.

Importantly, in the case of business, the issue of SR has emerged as a result of the need to achieve an ethical balance in profit-oriented activities, whereas in universities, it has emerged somehow "naturally" as a result of the role of universities (see Drobny, 2016). Put simply, this is a process implemented in a socially responsible way to educate future employees and conduct research to contribute to society (see Kędzierska, 2018; Kowalska, 2009; Ławicka, 2016; Piasecka, 2015). This perception of USR is expanded by Giuffre and Ratto (after Pabian, 2019) to include management that serves to disseminate and implement a set of general principles and specific values. Similarly, Markus and Govender (2023), considering universities as sites of transformation, describe four axes of social responsibility change: organization, knowledge, education and participation. The last two are related to teaching, but the authors see them as shaping the viewpoints of students through their participation in the community and holistic experience. This means that education should be continuous (lifelong) and sustainable. The first two axes of change, in turn, refer to the formation of meaning and social identity through the introduction of specific organizational practices and the creation of an organizational culture anchored in the ethical values of technical and scientific activities.

Teaching, research, or organizational aspects are realized in relation to different stakeholder groups (cf. Karwowska & Leja, 2018; Kowalska, 2009).

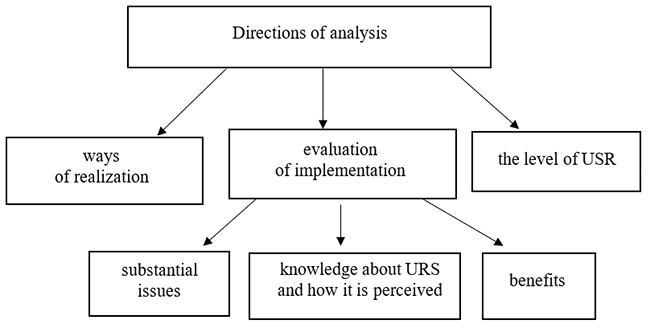

According to the authors, USR is analyzed with respect to three main areas (appendix 1): the manner in which it is achieved, determining the level of USR, and evaluation of implementation (figure 1).

The possibilities of introducing SR (good practices, programs) are presented mainly based on the example of a selected university (Cichowicz & Nowak, 2018; Marinescu et al., 2010; Merta-Staszczak et al., 2020). In contrast, Akpom et al. (2020), focusing attention on libraries, in addition to the types of SR activities that should be carried out in a university library and the real ways in which programs are implemented, also examine the attitudes of librarians towards SR activities.

Figure 1The Subject of USR Analysis

Source: authors’ own work.

When it comes to articles on evaluating URS, there are three notable criteria. The first relates to substantial issues, i.e. proper implementation on the one hand and compliance of activities with guidelines, norms, and rules on the other. Gaweł (2014) examined whether cooperation with business is only a declaration a point entered into the strategy, or whether it is truly implemented. The last issue was analyzed by the author through a study of relationships: opportunities for cooperation, its object and barriers. Batista et al. (2023), in turn, compared the compatibility of existing SR practices in the management of the Serra Talhada Academic Unit with those of the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco. Indicators related to people management activities were found to be the most relevant in the implementation of SR.

The second criterion can be defined as having knowledge of the university's applied activities and how they are perceived (see figure 1). Hungarian students have a positive attitude toward URS, and having knowledge about the activities in this area promotes their involvement in them (Burcea & Marinescu, 2011). Polish students show a similar attitude, however, they are not satisfied with the level of their own universities' SR activities (Pabian, 2019) or the quality of teaching regarding CSR (Cichorzewska, 2015). Analyzing the stakeholders of southern African universities, Markus and Govender (2023) have found that the university's promotion of CSR is fostered by three main elements: structure, culture and cause. Research on university employees, however, indicates that knowledge about and perceptions of SR (although positive) differ between employees of different departments, groups (academics, administrative staff), and age (Reichel et al., 2023). Differences in perceptions of SR among university stakeholder groups (managers, technical staff, lecturers and students) were also identified by de Sousa and team (2021). The authors suggest that universities should enhance the visibility of their activities and seek greater involvement of various stakeholders to make the university’s activities more effective.

The third criterion for evaluating a university's social responsibility is its benefits. These include the opportunity for a private university to gain a competitive advantage (Abdullah et al., 2020), shaping the image of the employer to make it more attractive to potential hires (Simpson &Aprim, 2018) and employee satisfaction (Chan & Hasan, 2019; Ismail & Shujaat, 2019).

Finally, an article was identified whose authors determined the level of social responsibility among Hashemite University lecturers (Al-batayneh et al., 2020). Finding this level to be moderate, they suggested measures to expand SR at the university, including training, creating programs, taking care of necessary resources, and rewarding active individuals (Al-batayneh et al., 2020, pp. 516-517).

In conclusion, SR is an important issue in the operation of universities. The analyses are conducted mainly among students. Although some studies have been conducted among academics, their purpose, as in the case of students, was to verify the perception, knowledge and evaluation of USR measures. There is little research on the social responsibility of universities with regard to employees. It is assumed that an organization's responsibility towards stakeholders includes areas such as building relationships that take into account the benefits and interests of the parties (here: universities and employees). In light of this, the important question is the specific nature of SR of a university in terms of university-employee relations.

Methods

Due to the difference between USR and CSR, and the perceived role of universities, the fulfillment of which depends largely on the researchers, the main objective of the study was defined as identifying the specific nature of social responsibility of universities towards employees.

A qualitative study was conducted (May 2023) using the in-depth group interview (IDI) method. The choice of the method was dictated by the need to explore the topic and by its specific advantages for gathering information necessary for the development of a measurement tool (interview scenario) to enable the collection of data of a quantitative nature (and thus conduct a representative survey).

Interviews were conducted with four groups (each from five to eight people) of academics that included research and teaching staff who did not hold management positions at the universities. The respondents work on indefinite employment contracts and have worked at the university for more than ten years. Long tenure ensures significant knowledge of the academic environment. A total of 23 people participated in the survey. Detailed characteristics of the respondent groups are provided in table 1. The respondents were employees of two state universities (U1 and U2), which are signatories to the USR Declaration. Both universities are academic universities, while no further information about the universities was disclosed due to assurances of anonymity that the authors gave to the respondents. Each participant in the study agreed to take part in the interview and consented to the manner in which it was conducted. The measurement tool was a framework interview scenario with open-ended questions (appendix 2).

Table 1The Surveyed Groups According to the Respondents' Characteristics

| Group/ University |

Number of persons in the group | Group characteristics | |||

| Sex | Academic title | University position | Employee group | ||

| Group 1/U1 | 8 | W1 W2 W3 W4 M1 M2 M3 M4 |

PhD PhD PhD MSc PhD PhD PhD MSc |

AP AP AP A AP AP AP A |

RDE RDE DE RDE DE RDE DE RDE |

| Group 2/U2 | 5 | W4 W5 W6 M5 M6 |

PhD PhD, DSc PhD PhD PhD |

AP AP AP AP AsP |

RDE RDE RDE RDE RDE |

| Group 3/U1 | 5 | W7 W8 W9 M7 M8 |

PhD PhD PhD PhD MSc |

AP AP AP AP A |

RDE RDE DE DE DE |

| Group 4/U1 | 5 | W10 M 9 M11 M12 M13 |

MSc PhD PhD PhD PhD |

A AP AP AP A |

RDE DE RDE DE RDE |

Note. W — woman; M — man; MSc — Master of Science; PhD — Doctor of Philosophy; PhD, DSc — Doctor of Science; A — Assistant; AP — Assistant Professor; AsP — Associate Professor; P — Professor; DE — didactic employee; RDE — research and didactic employee; U1 — the first university; U2 — the second university.

Source: authors' own work.

Results

Understanding SR

It is important to point out the lack of clarity in the respondents' understanding of CSR. The respondents mainly equated it with a way of managing an organization (W1: “CSR is a way of managing. You can make a profit through CSR also create a corporate image. Act according to values and make a profit”). This is a response to the negative practices of companies and an attempt to compensate various groups who suffer the consequences of these actions (M1: “CSR is a consequence of the exploitation of society. Exploitation doesn’t pay off for companies today”).

The respondents also pointed to the universal nature of SR. They considered CSR more as an expression of a value system than a business aspect (W10: “It actually comes from the home. It's in the upbringing, then also at the next levels of education. And the university continues this process, so that the graduate shows a certain behavior towards the employer”), as well as a human trait (M9: “Social responsibility is, one might say, the same as being human (...) now Machiavellianism is, as it were, being realized, which is precisely greed, which, so to speak, turns this world upside down. Everyone in his right mind needs a relationship with another person, because therein he realizes his humanity and is responsible for this relationship”).

Perception of the Concept of Social Responsibility at a University

Some respondents rejected CSR as a business practice, on the one hand, due to it being unrelated to the role of business (M3: “I'm against it. The role of business is to make money”) and on the other hand because of the unclear meaning of the term CSR. The respondents believe that it is possible to apply the principle of social responsibility to a university, saying at the same time that an essential condition is the authentic nature of the change. It is not enough to have another document that does not result in any action (M1: “Surely CSR can be applied, it is just a question of the purpose. There are many such actions that are taken and then turn out to be humbag”). Also, the proper purpose of introducing social responsibility has to be defined, and this cannot be reduced to public relations issues (W4: “if we're talking about CSR and not just PR, then yes”; “It comes down to the authorities: to convince employees that they want to implement it, and not just apply it to image related issues”).

Respondents identify factors limiting the possibility of implementing CSR at a university, and these are: mentality (W1: “It is possible to implement CSR at the university, but it would require mental changes: for example, women are still seen as those responsible for service issues”), lack of transparent rules, equal and fair treatment of employees (W4: “Implement it at our university? Well, I don't know... maybe only for the proverbial rabbit's-friends-and-relations”; “We are one university, but different rules apply in different units: we're a case of a state within a state”) and the willingness to change and foster openness (M2: “There is a lack of willingness to implement changes, a lack of openness”).

The respondents also see a deficit in values as an obstacle to implementing social responsibility at their university (M1: “If values were commonized, then they would be implemented - procedures wouldn’t be needed”). According to the respondents, a significant problem in implementing CSR at the university is a lack of trust (M3: “Well, there is a lack of trust above all. Everywhere, not just at the university”).

These two characteristics: responsible education and responsible use of public funds (M2: “A responsible university is first of all, it's responsible spending of public money. It's worth looking at the salaries of e.g. rectors”) are, in the opinion of the respondents, important in building the concept of USR. The educational process should be accompanied by the formation of appropriate social attitudes (M3: “The responsibility of the university is to educate students”; M1: ”but also to impart values to them, teaching them responsible attitudes”). The respondents also talked about the accountability of the university towards a wide range of stakeholders for the effects of its actions. These are different from the effects of other organizations' actions, and carry important values in themselves (M1: “A university responsible to whom? To us, employees, students, the local community, suppliers, society in general. Responsibility for upholding values to various stakeholders: for the word, for truth, for freedom of inquiry, for freedom of expression, for development”).

Some respondents note that social responsibility means going beyond the imposed legal regulations in pro-social activities, and universities do not always fully comply with these regulations. The problem, according to the respondents, concerns the adaptation of infrastructure to the needs of people with disabilities (M6: “The university should, first of all, meet legal conditions. For example, it should be adapted to the needs of people with disabilities. We don't meet the legal conditions, so what can be said about social responsibility conditions”) and providing adequate working conditions (M9: “If someone has too many activities scheduled, it is like being on a treadmill. It's a serious problem for occupational hygiene”).

The basis for shaping the university's responsibility towards employees, according to the respondents, are the needs of employees and the decision-makers' knowledge of them (M5: “It is necessary to know the needs of employees and take them into account”).

Another view expressed was that USR is not needed, because legal regulations sufficiently protect the interests of employees (W6: “CSR in the employee-employer relationship? Insofar as labor law allows us ). Respondents also believed that all employees (including functional employees”) form the organization and are responsible for the relationship, and jointly creating the rules of the university (W1: “CSR towards employees? For me, there is something wrong in this sentence. We are all employees. Rectors and deans too. The organization is created by us. We are self-governing enough to have a lot of influence on the operating rules. Responsibility of superiors to employees? This is ordinary human responsibility”).

At the same time, the respondents wondered whether compliance with labor and OSH laws is enough to ensure the organization's responsibility towards employees (M4: “Where is the line between SR towards employees and applying OSH rules? Where is the line between SR and taking care of the work atmosphere and culture?”). Some respondents recognize that any efforts to build relations between employees and the university depend not on established rules, norms, or laws, but on the will of employees (M8: “Law is one area. What remains is the volitional sphere, e.g. leadership style, communication. Here, simply responsibility is enough”). There is not always, according to the respondents, the will and readiness to defend one's own interests (M6: “We are taught humility at the university - sit quietly. We don't ask the employer for our rights”).

Possibilities for Introducing Social Responsibility Towards Employees

When asked about measures resulting from the university's stance on social responsibility, the respondents began by pointing out the problems they see in the university-employee relationship. First and foremost, they pointed out that the role of employees is undervalued (W9: “It feels a bit like being an unwanted child”; “We constantly have to be deserving”; “How can you talk about taking care of an employee? Our work is many hours long, and when we don't provide a break for ourselves, the employer won't do it either”). It was emphasized that supervisors let employees know that they are not important to the university (W7: “A student is a rare good, an employee - not necessarily”; “If we don't like it, there are plenty of other people to take our place”).

In addition, according to the respondents, their needs and problems are not understood by the university authorities. Communication takes place only when there is such a need on the part of the authorities (W2: “I asked for a meeting with the Rector more than a year ago. To date, I’ve had no answer”; W6: “it is absurd that the Rector only meets with us when he wants our votes. Why doesn't he meet with us once a year and talk to us?.... (...) no one listens to us”).

The respondents also pointed to an excessive teaching workload and the high demands regarding their academic activities (W10: “Because students come first. And they think that we will tun on the computer during a break and write an article for a high number of points in our field2”; W7: “I've been working for a long time, and I feel like I've been on an internship for a while - we have a lot of new subjects”).

Pressure to write articles for high-scoring journals causes disillusionment. There is emphasis not so much on the quality of the publication but the number of points that can be obtained. When the award is determined by respondents, such a form of motivation does not fully satisfy them (W8: “There are awards, but this is not good at all. It's the points that count. I get awards, but I'm not proud of it. I write what gives me points”). This is not conducive to social responsibility.

Considering the above, the respondents declare that there is no support from the university and direct superiors (W10: “There is a lack of people who would show these young academics how to do some things, and I'm not talking about some extraordinary care”; W8: “In 12 years I have had 5 bosses”). They express concern that any stumbling on their part could result in negative consequences. Also, in the case of conflict or disagreement in the employee-student relationship, the respondents believe that regardless of the situation, the university will take the side of the student (W7: “We are afraid: we try our best, and the student can do anything. When something happens there is an assumption that the student is right. They don't look into the situation”; M5: “The university has lawyers who have one goal: to sweep it under the carpet. All the blame is put on the employee, just so the university isn’t involved”).

The problem of unequal treatment also applies to the gender of employees (W10: “Equal treatment. I'm thinking about gender here. Maybe it's changing, but it's more a matter of young people, their approach rather than the other side [university authorities and superiors]”; W9: “Equality? Please check the gender of those in authority”).

The respondents have doubts about the employee evaluation system, especially the way students evaluate academic teachers (M11: “The way we are evaluated is irresponsible. The opinions of 5 students affect the final evaluation of an employee. How can something like this be taken into account?”).

The respondents identify the cause of some of the above-mentioned problems in factors beyond the control of the university (M13: “We complain a little too much. After all, the law restricts certain activities. And this affects responsibility towards employees and students. The law destroyed coffee meetings”; M11: “The university supports us as much as it can and knows the needs, such as team-building meetings (...). When there are external monies and projects – they are used for employees”). Some respondents perceive support and understanding from superiors (W5: “I can approach my superior and tell about different situations and support will be there for me. I don’t have to worry, and it was like that in my previous job, to go and tell them that, e.g., my child got sick”).

According to the respondents, employees are not always informed about the criteria for making decisions, especially those concerning labor issues (W9: “Decisions are made without employees. Those that affect them. It seems that they are dictated by some personal interests, and the consequences are borne by the employee”). These issues include how research funds are distributed (M5: “There should be a transparent monetary policy regarding grants and projects”).

According to the respondents, another important aspect of a university's social responsibility towards employees is taking care of their development. They note the role of training in ensuring an appropriate level of educational quality (M1: “The university should be ready to incur costs for the further training of employees, for their development, so that values can be transmitted in the best way possible. Otherwise the transmission of these values will be at a very low level”). The respondents emphasize that the university does not provide the necessary training to improve the skills of employees (M7: “Training is scarce and not targeted to the needs of employees”; W5: “At our university? Is there any training there?”). They are critical of the effects of the training they have attended (M7: “Even when there is training, such as on the needs of disabled students, nothing changes”).

The respondents are also dissatisfied by the inadequate funding, for example of research, publications, and conferences by universities and, as a result, inadequate support for employee development (W9: “You have to develop yourself, preferably with your own funds”).

A theme that came up in the context of a university's social responsibility toward employees was relationships. According to the respondents, relationships are the glue of the academic community (M11: “The English have concluded that success is relationships and working together”). Thanks to good relationships, it is possible to overcome adversities (M11: “Thanks to personal relationships, we are still able to keep some good habits and perhaps here is a hint to the authorities of what to support. And despite complaints and limitations, it is these personal relationships that hold”).

At the same time, they see a threat to the quality and durability of relationships in being overloaded with responsibilities (W8: “There is also no time for such integration meetings. I remember being asked at conferences where we were from, and how we spent time together. There is no such thing anymore”).

The respondents also point out working conditions related to equipment in the classrooms and the training they receive for teaching. They emphasize that this affects job satisfaction and, as a result, the quality of work (W5: “The environment affects your psyche. As when walls in your room are cracking, long since unpainted, and you have a view of buildings instead of greenery. I don't like working in my office. I prefer to work at home”). Another problem, according to the respondents, is the differences in the quality of infrastructure in the various departments (M12: “On top of that, you enter the room, it's hot in there- there is air conditioning but it isn't working. Interestingly, in the halls of other departments - it does work. Similarly, you can go to them with just a flash drive and not all the equipment - projector, laptop”).

Consequences of USR for Employees

The respondents express doubts about whether there will be any changes when social responsibility is introduced at the university.

They also do not think that social responsibility can be guaranteed through orders or procedures (M13: “I don't think anything can be done by the sheer introduction of procedures”; M11: “Procedures can only be introduced formally, that's how it was with ISO, it was just a tool, a formality. I'm afraid it won't produce results (...). Social responsibility comes from who I am and not from having an objective regulation that I want to fulfill”). The respondents emphasize that responsibility stems from a system of values (M5: “It should rather come from our relationships and from the fact that we ourselves want to be better and improve things, it's hard to imagine that it will work with procedures”), and is a manifestation of will and not procedures (M9: “Regulations are not bad (...) they are suitable, but not for everything. Where there is an act of will, they are not necessarily welcome”). Concerns have been expressed about the condition of the organization and its members, if procedures must be introduced to ensure core values (W10: And it is sad that even for such basic things, which should be from a young age, that we have to have procedures”).

In addition, the respondents wondered whether the introduction of USR might result in an increase in tasks and responsibilities for employees. There were opinions that additional duties related to the introduction of USR should be performed by an employee specially hired for that purpose (M3: “Will we add USR-related tasks to someone's current ones? I don't see it. Someone else should be hired, then maybe it will be more feasible”). At the same time, the respondents are aware of the competence they need to implement USR procedures and activities. However, they are not convinced that they would like to be involved in this process (M5: “As academics, we have the ability to create certain activities from the bottom up. The only question is: Do we want to?”). The respondents' opinions are not only due to work overload and fear of additional responsibilities. The respondents state that the need to hire people to implement USR is dictated by a concern for the stature and reality of USR activities.

Most respondents were not aware that the university is a signatory to the USR Declaration (W5: “Have we signed a declaration????”). The respondents are of the opinion that the USR Declaration will change little in the university's activities and mutual relations. First, the Declaration is very general in nature, with no indication of specific actions. In the opinion of the respondents it is an empty record. (M6: “We can sign even the Geneva Convention, but it ... should not look like this”; “Why sign something, if no one listens to us anyway? Certificates are needed, e.g. those setting a standard but then - that's the way it is in companies – they are like a square peg in a round hole”). Secondly, it is not enough to sign the Declaration, you need to apply it in practice. Thirdly, the application of the provisions requires their acceptance (W3: “For it to work, there must still be general acceptance”).

Conclusion

There is a consensus among respondents that social responsibility can be applied to universities. In the opinion of the respondents, the specific nature of USR is due to the role of the university and the principles according to which it operates.

Taking into account the opinions presented, regardless of whether the respondents agree with the precepts of CSR, they believe that the social responsibility of an organization should be based on core values (freedom, dignity, respect, honesty, etc.).

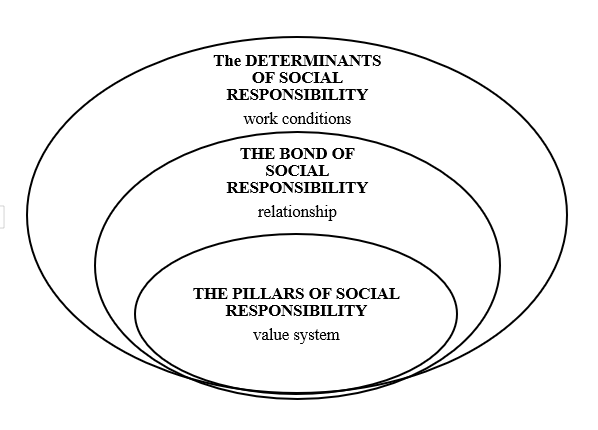

Figure 2Social Responsibility of a University Towards Employees

Source: authors' own work.

The volitional aspect is an important aspect of forming responsible university-employee relations. The respondents expressed the view that the appropriate quality of these relations, in turn, is a determinant of the university's social responsibility towards its employees (cf. Figure 2). They stated that relationships should be built based on a universal value system. The importance of the value system in the creation of USR is pointed out by Calderon's team, among others (de Sousa et al., 2021). At the same time, the difficulty they highlighted in conceptualizing social responsibility stems from choosing the ethical principle on which the university's operations should be based.

According to ISO 26000, these are: accountability, transparency, ethical behavior, respect for stakeholders, respect for the rule of law, respect for international standards of conduct, and respect for human rights (after Pabian, 2019).

In contrast, the results of the survey show that the value system should include values such as:

- support (in the sense of providing assistance, being available, being present in difficult situations),

- fairness (in the sense of impartiality),

- transparency (in the sense of openness),

- equality (no division based on gender, race or social position),

- freedom (in the sense of the ability to make choices),

- causality (manifested as the ability to act),

- influence (i.e., employees having a say in the functioning of the university),

- dignity (respect for human values, mutual respect),

- partnership (in the sense of a relationship based on mutually agreed terms),

- trust (the belief that someone's words, information, actions are true),

- honesty (in the sense of a relationship based on honesty and adherence to moral standards),

- quality (in terms of the value of the actions taken).

Determinants of the quality and sustainability of both university-employee and peer-to-peer employee relationships were seen to include: relational issues, administrative issues, research, teaching, motivational issues, financial issues, development, ecological issues, and working conditions.

It is important to emphasize the skeptical attitude of the respondents towards activities concerning the formation and implementation of USR. The views held were as follows:

- many of the changes that universities are making are not practical,

- the activities deal with such basic issues that they should not be regulated,

- basic values, despite the record, are not respected at universities,

- an example should be set from the top,

- employees will not be fully committed due to the already existing overload.

The statements of the respondents of the surveyed universities are similar. Employees are disillusioned and they have similar demands - they consider the foundation for building the social responsibility of the university to be universal human relations. U1 employees were slightly more likely to emphasize the role of physical working conditions, while U2 employees paid more attention to issues related to academic development.

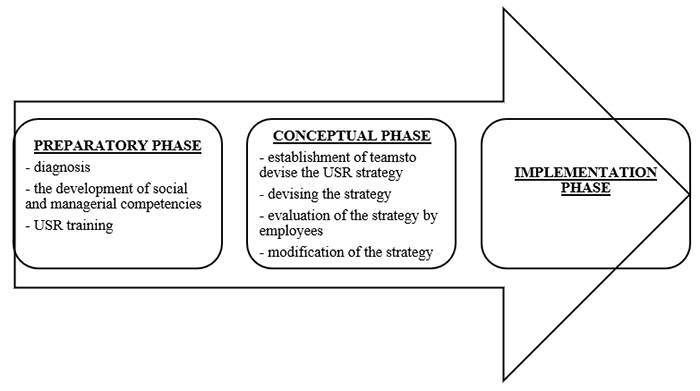

The attitudes and, consequently, the activity of employees in the implementation of USR can be positively influenced by the behavior of university authorities and direct supervisors (cf. Szelągowska-Rudzka, 2018, p. 268). Hence, work on change should begin with the top management (rectors, deans) and gradually include unit managers and then employees. This suggests gaps between employee expectations and perceptions regarding the issues indicated. Based on the literature, the survey results, and their own conclusions, the authors produced a diagram showing the process of development of a university's social responsibility strategy towards employees (cf.: Figure 3). This process is illustrated in three phases. The first stage of the preparatory phase of the USR.

Figure 3The Process of Developing a University's Social Responsibility Strategy Towards Employees

Source: authors' own work.

development process should be a diagnosis. This suggestion is based primarily on the opinions of the respondents. They do not have faith in pre-imposed procedures that are not aligned with real problems. The respondents suggest that the social responsibility strategy of the university should be based on a value system. Similar conclusions can be found in the literature (de Sousa et al., 2021). The strategy needs to address the value system on which relationships are based and the working conditions that affect the quality and sustainability of relationships. In addition, the level of social and managerial competence and knowledge of USR, as well as the needs of employees, can be studied. Hence, training and workshops aimed at developing social competencies (communication, empathy, assertiveness, ability to cope with stress, cooperation, etc.) and managerial competencies (e.g., decision-making, motiving people) among managerial-level employees may be important. They are a prerequisite for the creation and development of relationships, and the respondents emphasized the importance of these [competencies]. Enhancing social competencies in both functional and non-functional employees may constitute the second stage of the preparatory phase. The third stage of the preparatory phase should be training to increase knowledge about USR. Information on the benefits of introducing the concept at universities would be particularly important. The results of the diagnosis and increased awareness of USR could be the basis for moving from the preparatory to the conceptual phase. In the conceptual phase, a USR strategy should be developed, taking into account the needs of the workers and the deficiencies revealed by the diagnosis. This measure would be dealt with by teams composed of management and employee representatives (cf. Al-batayneh et al., 2020, pp. 516-517; Szelągowska-Rudzka, 2018, p. 269). The prepared strategy should be evaluated by the academic community. The next step is the implementation phase. It seems that a change in awareness, attitudes and an increase in social competencies among management and employees will play a key role in building and maintaining high-quality relationships. The authors assume that introducing USR in this way is likely to gain the acceptance, trust and [commitment] of employees. These issues will be the subject of further research of a quantitative nature.

In conclusion, the purpose of the article was to identify the specific characteristics of USR towards academics. Based on the literature review and the results of a qualitative study, i.e., in-depth group interviews among academics at two universities, a model of USR towards academic employees was developed. This model, together with the concept for developing a strategy of social responsibility of universities towards employees, is the authors' proposal for further development of knowledge in the analyzed subject area. At the same time, this requires validation in further quantitative research.

This study has several limitations that must be taken into account. Firstly, although, due to its qualitative nature, the conducted research provides deep insights into the issue being studied, the study has some inherent methodological limitations. Also, while appropriate for qualitative research, the relatively small research sample limits the ability to apply the results to populations in general. Secondly, the study encompassed non-management academics. Other groups of employees, including administrative staff or librarians, as well as those in managerial positions, may have a different opinion of URS.

Thirdly, employees of other universities might have different perceptions, for example. due to form of ownership, size, or location, of the implementation of USR than those identified. Finally, the respondents have a long history of service, of ten years or more. This certainly means that they are familiar with the specifics of the university, and are highly experienced. At the same time, they may also experience professional burnout, which may affect their evaluations and attitudes. Ultimately, one must point to the cultural context. While universities may be characterized by the indicated third mission, the ways in which it is implemented may at the same time be related to the rules (legal, social) of the country in which it operates.

References

- Abdullah, Y. H., Agala, S. R., & Abdulkarim, P. A. (2020). The role of social responsibility accounting on achieving competitive advantages (An empirical study from perspectives of a number of employees in accounting and financial departments in a number of private universities in Iraqi Kurdistan Region). International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 7(3), 212-235.

- Akpom, Ch. Ch., Onyam, I. D., & Benson, O. V. (2020). Attitude of librarians' towards provision of corporate social responsibility initiatives in state university libraries in south Nigeria. Library Philosophy & Practice, 4130, 1-23.

- Al-batayneh, O. T., Al-Zoubi, Z. H., & Mohammad Rawashdeh, R. (2020). Attitudes towards social responsibility among faculty members of the Hashemite University. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 9(3), 505-519. https://doi.org/10.13187/ejced.2020.3.505

- Batista, A. S., Albuquerque, J. de L., Mandú, M. J., da S., Correia-Neto, J. da S., Peixoto, C. S. B. de S., Filho, R. A. de M., Ventura, A. A. de O., & Diniz, J. R. B. (2023). Labor relations as an indicator of social responsibility in the perception of employees at the Serra Talhada academic unit of the Federal rural University of Pernambuco. Revista de Gestao e Secretariado, 14(1), 385-403. https://doi.org/10.7769/gesec.v14i1.1519

- Burcea, M., & Marinescu, P. (2011). Students' perceptions on corporate social responsibility at the academic level. case study: The faculty of administration and business, university of Bucharest. Amfiteatru Economic, 13(29), 207-220.

- Chan, T.-J., & Hasan, N. A. M. (2019). Predicting factors of ethical and discretionary dimensions of corporate social responsibility and employees’ job satisfaction in a Malaysian public university. International Journal of Business and Society, 20(3), 946-967.

- Cichorzewska, M. (2015). Społeczna odpowiedzialność biznesu (CSR) jako istotny element edukacji studentów uczelni technicznej [Corporate social responsibility (CSR) as an important element of education for technical university students]. Edukacja-Technika-Informatyka, 1(11), 188-194.

- Cichowicz, E., & Nowak, A. K. (2018). Społeczna odpowiedzialność wyższych uczelni w Polsce jako przejaw realizacji idei ekonomicznej teorii zrównoważonego rozwoju [Social responsibility of universities in Poland as implementation of the idea of the economic theory of sustainable development]. Gospodarka w Praktyce i Teorii, 50(1), 7-19. https://doi.org/10.18778/1429-3730.50.01

- Drobny, P. (2016). Społeczna odpowiedzialność uniwersytetu ekonomicznego [Social responsibility of the economic university]. Ekonomista, 3, 383-402. https://ekonomista.pte.pl/pdf-155605-82434?filename=Spoleczna.pdf

- Gałat, W. (2018). Społeczna odpowiedzialność uczelni w zmieniających się warunkach społeczno-gospodarczych [Social responsibility of universities in changing socio-economic conditions]. Zeszyty Naukowe. Organizacja i Zarządzanie. Politechnika Śląska, 123, 143-153.

- Gaweł, A. (2014). Business collaboration with universities as an example of corporate social responsibility - a review of case study collaboration methods. Economics and Business Review, 14(1), 20-30. https://doi.org/10.18559/ebr.2014.1.823

- Ismail, Z., & Shujaat, N. (2019). CSR in universities: A case study on internal stakeholder perception of University Social Responsibility. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 6(1), 75-90. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.61.5256

- Karwowska, E., & Leja, K. (2018). Czy społeczna odpowiedzialność uniwersytetu może być bardziej odpowiedzialna? Szanse wynikające z koopetycji uczelni [Is there any room for improvement for university social responsibility? Coopetition as a catalyst]. e-mentor, 3(75), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.15219/em75.1357

- Kędzierska, B. (2018). Nauki humanistyczno-społeczne stymulatorem zrównoważonego rozwoju społeczeństwa, czyli statystyka punktów i cytowań vs społeczna odpowiedzialność uczelni [Humanities and social sciences as a stimulator of sustainable development of society, i.e., statistics of points and citations vs. social responsibility of universities]. Rocznik Lubuski, 44(2), 109-117.

- Kowalska, K. (2009). Społeczna odpowiedzialność uczelni [University social responsibility]. Zeszyty Naukowe Małopolskiej Wyższej Szkoły Ekonomicznej w Tarnowie, 2(1), 289-300.

- Ławicka, M. (2016). Społeczna odpowiedzialność uczelni wyższej w Polsce [Social responsibility of universities in Poland]. Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Humanitas. Zarządzanie, 3, 207-220.

- Mackiewicz, H., Spodarczyk, E., Szelągowska-Rudzka, K., & Teneta-Skwiercz, D. (2018). The Social Responsibility of universities in the students’ opinion – Results of a pilot research. In A. Nalepka, & A. Ujwary-Gil (Eds.), Business and non-profit organizations facing increased competition and growing customers’ demands (pp. 423-435). Foundation for the Dissemination of Knowledge and Science “Cognitione”; Wyższa Szkoła Biznesu.

- Marinescu, P., Toma, S., & Constanti, I. (2010). Social responsibility at the academic level. Study case: The University of Bucharest. Studies and Scientific Researches: Economics Edition, 15, 404-410. https://doi.org/10.29358/sceco.v0i15.147

- Markus, E. D., & Govender, N. (2023). Can universities of technology in South Africa achieve transformation by promoting a culture of social responsibility among academic and student agents? Public Organization Review: A Global Journal, 23, 1571–1589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-023-00701-9

- Merta-Staszczak, A., Serafin, K., & Staszczak, B. (2020). University social responsibility on the example of Wrocław University of Science and Technology. Annales. Ethics in Economic Life, 23(4), 91-107. https://doi.org/10.18778/1899-2226.23.4.06

- Pabian, A. M. (2019). University social responsibility in the opinion of students. Forum Scientiae Oeconomia, 7(4), 101-117. https://doi.org/10.23762/FSO_VOL7_NO4_7

- Piasecka, A. (2015). Społeczna odpowiedzialność uczelni w kontekście wewnętrznego zapewnienia jakości [University social responsibility in the context of internal quality assurance]. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, 378, 309-319.

- Reichel, J., Rudnicka, A., & Socha, B. (2023). Perspectives of the academic employees on university social responsibility: a survey study. Social Responsibility Journal, 19(3), 486-503. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-08-2021-0336

- Simpson, S. N. Y., & Aprim, E. K. (2018). Do corporate social responsibility practices of firms attract prospective employees? Perception of university students from a developing country. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 3(6). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-018-0031-6

- Sousa, J. C. R. de, Siqueira, E. S., Nobre, L. H. N., & Binotto, E. (2021). University social responsibility: perceptions and advances. Social Responsibility Journal, 17(2), 263-281. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-10-2017-0199

- Szelągowska-Rudzka, K. (2018). University social responsibility and direct participation of academic teachers. In P. Ravesteijn, & B. M. E de Waal (Eds.), Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance (pp. 264-272). Academic Conferences and Publishing International.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5964-2049

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5964-2049