About the article

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em77.1385

The article is in the printed version on pages 24-29.

Download the article in PDF version

Download the article in PDF version

How to cite

Gasparini, A. (2018). Building Tasks with Instant Messaging Apps. e-mentor, 5(77), 24-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15219/em77.1385

E-mentor number 5 (77) / 2018

Table of contents

About the author

Footnotes

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instant_messaging#cite_note-43

Building Tasks with Instant Messaging Apps

Alice Gasparini

Introduction

Knowing a foreign language is an asset for people who want to travel, work or move in our globalized and rapid-changing world. There is a constant (Widdowson, 1990, p. 2) need to adapt the language teaching to the changes happening in the world. Thanks to new technologies, language learning may become more effective and attractive, allowing the learner to feel closer to the society and the country in which the language is spoken. In particular, mobile technologies enable a more personalized approach to learning by using target languages to resolve communication challenges. 'In addition, mobile technologies offer affordable learning resources (Kukulska-Hulme, et al., 2017, pp. 217-233).'

On the other hand, it is well-known that technology itself is neither a method nor an approach. It is a tool. According to that, teachers need to rethink their way of teaching to create new models in which pedagogy and technology may be fully integrated. The author of this paper presents the experience of a traditional classroom second language course blended with technology-mediated tasks. That solution has turned out an excellent way to insert new and highly motivating activities (developed in a virtual environment) as well as to guide students among a large number of available resources.

This blended solution applies TBLT (Task-Based Language Teaching) as a method of learning the second language by completion of real word tasks.

What is a task?

Micheal Long defines 'a task' as a piece of work undertaken for oneself or the others, freely or for some reward. Thus, examples of tasks include painting a fence, dressing a child, filling out a form, [...] making hotel reservation, finding a street destination (Long, 1985, p. 389).

According to David Nunan, 'a task' is a piece of classroom work which involves learners in comprehending, manipulating, producing or interacting in the target language while their attention is principally focused on meaning rather than form (Nunan, 2004, p. 10). Also, Jane Willis describes it as a goal-oriented activity in which learners use language to achieve a real outcome. In other words, learners use whatever target language resources they have to solve a problem, do a puzzle, play a game or share and compare experiences (Willis, 1996, p. 53).

The task is an authentic, connected to real life, goal-oriented activity. The idea of using authentic activities related to real world communication represents a big revolution in second language teaching. It is no longer focused on the description of the foreign language but the use of it. According to Hymes communicative competence (1972), the language in action has become crucial, and this importance generates the need to invent and propose authentic and realistic tasks.

In the literature, one can find two main task models. First, proposed by Willis, includes three phases - pre-task, task-cycle, and post-task. More detailed information about it has been provided in the section Implementing tasks with Whatsapp. In the second model, defined by Mike Long, the first phase includes the needs' analysis that leads to selection the main task types such as 'making a hotel reservation' or 'booking a holiday house.' Once selected the target tasks, for example 'making a hotel reservation', the teacher creates the pedagogical tasks, smaller steps which will lead the students to their target task. Assessment of learners' progress and program evaluation constitute the last phase of the task.

In the method used in this case study, the two models were mixed. The first phase, the needs analysis and the last phase (the assessment of the learners and the program) come from Long's model, while the task development follows Jane Willis'.

Task and Technology

In our everyday life, we carry out numerous tasks supported by technology tools such as writing emails, chatting with other people, and using Google to search books or new holiday destinations. All of them imply linguistic skills: reading, writing, understanding and selecting information. Computers, smartphones, and tablets allow us to make something real such as creating various materials and texts as well as communicating with people on the other side of the globe. That makes them ideal for experimenting with the 'learning by doing' - the Deweyan principle of experiential learning.

Web 2.0 technologies are unique environments in which students can 'do things' by technology-mediated transformation and creation processes rather than just reading about language and culture in textbooks or hearing about them from teachers. Thanks to the new technologies, students can feel involved in active learning and holistic tasks, and therefore they are perfect candidates for their integration in TBLT (Van den Branden et al., 2009).

Developing a task using technology boosts students' motivation and participation. From the very beginning learners are aware of the purpose of the activities they are requested to perform; therefore they can focus on the skills or knowledge needed to accomplish them.

In this paper, the author presents the experience of the second language acquisition classroom setting blended with tech-mediated tasks. The word 'blended' implies variety, and as it is shown later, variety enhances motivation. Tech-mediated activities mixed with more traditional classroom setting may be a solution for those who are skeptical about new technologies or are not accustomed to an entirely virtual environment.

While applying new technologies in a language learning course, teachers need to consider whether the students are open and willing to try them. Effective and satisfactory learning experience depends on a combination of factors such as the students' individual learning style and the influence of so-called cultural learning styles, according to which cultural upbringing plays a decisive role in determining a student's learning style (Heredia, 1999, p. 2).

Motivation and variety

Blending different teaching approaches or instruments offers incredible advantages for the students and a teacher. It implies variety, novelty and new challenges for both sides. Introducing new activities or changing learning environment gives students the chance to put themselves to the test in various conditions. The teachers' winning strategy to fight with students' lack of motivation is to create a learning path with some degree of variety. Such elements are listed by Balboni as pleasant emotions linked to teaching; they reinforce the idea that learning a language could be unpredictably stimulating (Balboni, 2002). Moreover, they provide students an opportunity to switch between the traditional environment and technological one as well as to try out different learning settings.

Technology may also have emotional advantages for the students who might feel shy and fearful about using the language they are studying. According to Gónzalez-Lloret and Ortega, language learning tasks mediated by new technology can help to minimize students' fear of failure, embarrassment or losing face; they may raise students' motivation to take a risk and be creative while using the language to make the meaning (Gónzalez-Lloret, Ortega, 2014, p. 4).

How to choose the appropriate tasks and technology

One of the first and most important steps when creating and implementing a language course is the needs analysis (NA). Understanding what the needs of a program are, and whether they are met by the program, is a fundamental principle for the implementation of any program (Patton, 1997).

We can define the needs analysis as the systematic collection and analysis of the information necessary for defining a defensible curriculum. The needs analysis becomes crucial to select or create the right tasks for the students. Except for linguistic needs analysis, students' digital literacy is also vital. Thanks to that, one can understand and choose better technology which is most suitable to realize the selected tasks. There are a few models of needs analysis. Witking and Altschuld (1995) propose a three-phase paradigm:

- development of a plan allowing to identify the major needs, issues, and areas as well as to choose what data, sources, methods to be used;

- collecting, analyzing and synthesizing data;

- the prioritization of needs, development of an action plan and evaluation of needs analysis.

Brown (2009) also designs the three-stage model for the NA - preparing NA, conducting NA and using results to decide objectives. Both models are based on mixed-method research and multiple sources. Some useful methods of carrying out the linguistic needs analysis and technology need analysis include interviews, questionnaires, and observation of interactions among the students.

Assessment and tech-mediated task

Tasks may unfold interesting opportunities in the language learning assessment. They present goal-oriented, contextualized challenges that prompt examinees to deploy cognitive skills and domain-related knowledge in authentic performance rather than merely displaying what they know in selected-response and other discrete forms of tests (Kane, 2001, p. 322).

As mentioned before, learners who accomplish the task are requested to carry out a performance defined by the Council of Europe as a relevant performance in a (relatively) authentic and often work- or study-related situation (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 187).

Performance-based assessment is criteria-related because the teacher needs to evaluate student's ability to accomplish the task, their skills performed in developing it, and the way they use the language in real situations rather than presenting what they know about the language. Establishing effective and objective criteria is one of the biggest challenges.

When teachers decide to base their assessment on the performance of a task, they should also decide whether to evaluate and include in the rubrics the performance itself or the language used by the learners.

As Gónzalez-Lloret points out, criteria should be developed by a domain expert who knows what a successful performance of the task looks like, [...] based on the target language and the observations conducted through the needs' analysis (Gónzalez-Lloret, 2014, p. 55).

accomplish the assessment. Teachers can easily use these tools to assess their students' writing skills by observing and grading the conversations without interfering with it. As mentioned in the case study later on, students create the video or audio files that may be used for their skills evaluation. Thanks to that, it is possible to generate useful feedback on their language progress.

Using commonly accessible software like Skype or Google Hangouts one may test students speaking and listening skills. It is worth to emphasize that students should be familiar both with the task and the selected technology before taking the test.

Case study

Mobile Learning

When deciding to use technology during the course, one should consider its availability, students linguistic needs, and their digital literacy. That first aspect should not be a problem in the digital era when people have broad access to devices such as computers, tablets, and smartphones. However, it is essential not to take this availability and familiarity for granted. The too challenging tech-mediated task or too tricky and unfamiliar tool may cause students frustration, and in consequence losing the motivation to learn a new language.

People use smartphones for communication, sending pictures, writing e-mails, searching for information but they rarely consider them as a learning tool or as a tool allowing to achieve ubiquitous learning experience.

Mobile tools may represent a bridge between classroom learning environment and out-of-the-classroom world. As Kukulska-Hulme states dichotomies between formal and informal learning may also require reconsideration [.], language learning now increasingly traverses the classroom and learning takes place in virtual spaces and out in the world (Kukulska-Hulme, 2017, p. 218).

With mobile devices, teachers have the opportunity to bring the outside world inside the classroom and make their courses more real and authentic. The challenge for them is to find a new pedagogical framework allowing to combine better these two worlds and give their students the support necessary for searching and using information available in the virtual world.

Teachers face the challenge of identifying and creating synchronous real-world learning tasks that are skillfully woven into the everyday life (Kukulska-Hulme, 2017, p. 219).

Instant messaging applications

Instant messaging is a set of communication technologies used for text-based communication between two or more participants over the internet or other networks. The conversation is real-time, and the most advanced applications allow for sending files, links, and video chatting as well. Since 2010 the Instant Messaging platforms are in decline, and today instant messaging takes place mostly on messaging apps. According to Wikipedia the main of them are WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, WeChat, Line, Telegram, Snapchat, and Viber. They all have similar functions such as real-time chat, sharing files, taking pictures and video chatting.

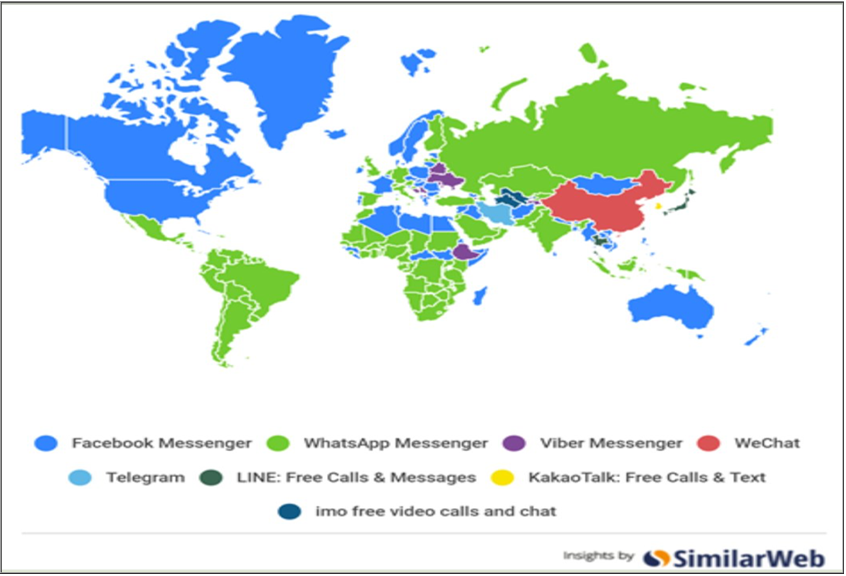

Geographically these technologies seem to have their regions of domination. Facebook Messenger is widely used in the USA and some European countries, Whatsapp in European countries, Russia and South America (Figure 1) and Wechat in China.

Source: Similarweb, https://twitter.com/stocktwits/status/975774113565429760

These functions are highly interesting from a second language acquisition perspective. They offer the opportunity to use various texts and files. The multimodality of the instant messaging apps may be an asset if used for implementing a tech-mediated task.

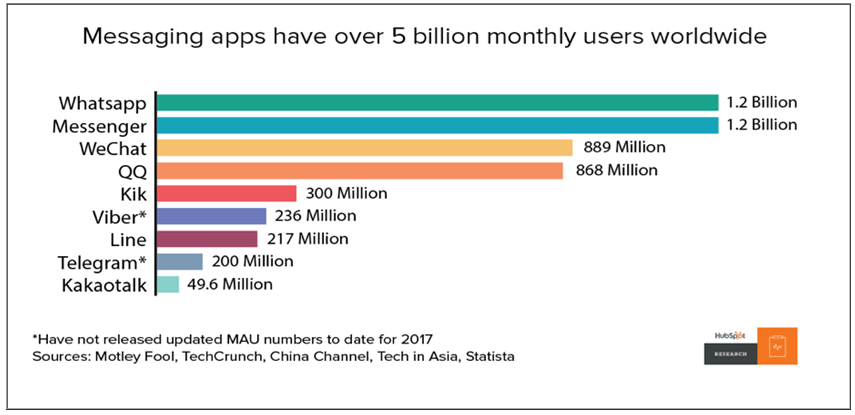

More than 5 billion people use instant messaging apps every day. Whatsapp and Messenger have more than 1 billion users each, Wechat - almost 900 million. They are They are heavily used for communicating as well as sharing photos and video (Figure 2).

Source: : https://research.hubspot.com/charts/messaging-apps-have-over-4b-monthly-active-users.

The case study described in this paper is based in Moscow, Russian Federation where Whatsapp is the most popular instant messaging app. That is the reason why this application has been chosen for implementing some tasks within the Italian language course offered by the Italian Institute of Culture in Moscow.

Implementing tasks with Whatsapp

The technology in task-based learning was tested with the group of 12 students attending the B1/B2 course. The students of the Italian Institute of Culture chose Italian as a foreign language mainly for private reasons (nearly 75%). They often travel to Italy, have a house in this country or simply love Italian culture. Nearly 20% of students learn Italian for professional reasons. They are interested in studying or working in Italy. Only 5% of the learners already work for Italian companies or use this language at work.

The first step taken in this case study was making the needs analysis to identify the linguistic needs and choose the best technology tools. It was conducted by using the interview and the questionnaire that covered questions about students' digital literacy and their preferences for using computers, tablets or smartphones. The mobile tool was adopted because it was the preferred choice of the students. Furthermore, the choice of personal smartphone was also supported by the BYOD (bring your own device) approach, an increasingly widespread orientation that consists in requiring users to be equipped with personal tools of work and learning such as smartphones and tablets (Fratter, 2016, p. 119). Learners use their mobiles for different purposes, such as personal, leisure and training. That familiarity allows them to adjust their devices also for the learning. Students chose Whatsapp because it is widely used and known.

Whatsapp allows exchanging the text messages, images, video, audio recordings, documents, geographical positions, making VoIP calls and video calls with anyone who has this application and access to the internet.

As mentioned before, the development of the task has been based on Jane Willis' model and it involved three main phases:

-

. pre-task - the teacher presents instructions and divides class into groups or pairs; learners prepare for the task with the help of the teacher;

. task cycle phase - accomplishing the real task divided into three phases, performing task in pairs with the oral or written report and its presentation;

- post-task - focused on the form such as grammatical structures and lexical aspects not fully internalized by learners.

In the case study, the teacher always adjusted this last phase according to the task objective. As mentioned before, the tasks were created following the results of the Needs Analysis taking into account the syllabus of the course book.

Each task was performed according to the same scheme. First, the teacher created a class group chat and work group chats on WhatsApp. Thanks to that, small groups of students could communicate with each other independently. For example, one of the tasks that students got was: Find an apartment for your summer holiday in Italy. Discuss this problem with other students and choose one option. There were three groups of students. Each group had a chat thread where they could discuss the topic. After the teacher sent the main task, in this case, three links to the apartments offered on Airbnb website in three different destinations, and students should have started to chat about the topic.

The teacher followed the conversation without interfering in it. He/she offered his/her help only when it was necessary or requested by learners. The chat worked as a virtual working group where the teacher observed the progress without interfering.

For every task, the teacher used Google Docs to support and guide the students in the process of reading and selecting the essential information. In the described example, students had to look for some specific information on the website, such as price, house location, facilities, number of guests, a policy of cancellation, and filling the given table. Learners had to choose the best house and then to prepare the report covering their actions.

In the third and last phase of the task cycle, students should have presented that report. They could choose different ways of presentation such as reading their work in the classroom, showing the video or audio file. Since the first part of the task was developed and focused on written skills, the final report served for checking the aural skills.

Assessment and evaluation of students'work

The assessment phase took into consideration both the Whatsapp chat and the final outcome of the task. Scale from 1 to 5 was used in evaluation.

The assessment criteria included:

- accomplishment of the task,

- communicative effectiveness,

- fluency and correctness.

Furthermore, the questionnaires were used to evaluate the overall experience. Students answered five questions concerning different aspects of the experience:

- overall experience,

- the tasks,

- use of technology,

- applied mobile tools and instant messaging app,

- the report.

Students could rate every aspect using the scale from 1 to 5, where 5 meant very useful/very positive and 1- not useful/not positive at all. Apart from the grade on the scale they could also add comments.

Conclusions

This experience was very interesting both for students and for the teacher. Students accomplished all the tasks. They received feedback about their progress and learning stage. It was simultaneously challenging and helpful providing students and teachers an opportunity to judge and observe the effectiveness of the pedagogic activities (Gónzalez-Lloret, 2014, p. 54).

In general, 80% of the students considered this experience to be beneficial and positive. As for the tasks, 90% of students thought that they were very useful and positive learning activities. Opinions about using the instant messaging app were age-related. While 75% of students felt comfortable using Whatsapp for language learning purposes, the remaining 25% of them found using this app as challenging. They suggested using other devices (with a bigger screen) like a tablet or computer as well as other software or platforms (not only the instant messaging app). The last question in the questionnaire concerned the report; 85% of the learners considered it useful and positive. They also appreciated the possibility to present it in different ways.

References

- Balboni, P.E. (2002). Le sfide di Babele. Torino: Utet Universita.

- Brown, J.D. (2009). Foreign and second language needs analysis. In M. Long, C. Dought (Eds.), The Handbook of language teaching (pp. 269-293). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (2001). Strasbourg: Council of Europe, Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages

- Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based Language Learning and Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fratter, I. (2016). Il Mobile Learning e le nuove frontiere per la didattica delle lingue. In D. Troncarelli, M. La Grassa (Eds.), Orientarsi in rete. Didattica delle lingue e tecnologie digitali (pp. 110-127). Siena: Becarelli.

- González-Lloret, M. (2016). A Practical Guide to Integrating Technology into Task-Based Language Teaching. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

- González-Lloret, M. (2017). Technology for Task-based Language Teaching. In C.A. Chapelle, S. Sauro (Eds.), The Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 234-247). Oxford: John Wiley & Son.

- Heredia, A. (1999). Cultural Learning Styles. The Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC). Digest and Publications, 10. Retrieved February 25, 2019 from http://library.educationworld.net/a12/a12-166.html.

- Hymes, D.H. (1972). On Communicative Competence. In J.B. Pride, J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics. Baltimore, MD: Penguin Education, Penguin Books Ltd.

- Instant messaging (n.d). Retrieved February 25, 2019 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instant_messaging#cite_note-43.

- Kane, M.T. (2001). Current concerns in validity theory. Journal of Educational Measurement, 38, 319-342.

- Kukulska-Hulme, A., Lee, H., Norris, L. (2017). Mobile Learning Revolution: Implications for Language Pedagogy. In C.A. Chapelle, S. Sauro (Eds.), The Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 217-233). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

- Long, M. (1985). Input and second language acquisition theory. In S. Gass, C. Madden (Eds.), Input in Second Language Acquisition (pp. 377-393). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

- Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Patton, M. (1997). Utilization of focused evaluation: The new century text. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Van den Branden, K., Bygate, M., Norris, L. (Eds.) (2009). Task-based language teaching: A reader. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Villarini, A. (Ed.) (2010). L'apprendimento a distanza dell'italiano come lingua straniera. Modelli teorici e proposte didattiche. Firenze: Le Monnier.

- Widdowson, H. (1990). Aspects of Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wiggins, G. (1998). Educative assessment: Designing assessments to inform and improve student performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Willis, J. (1996). A Framework for Task-Based Learning. London: Longman.

- Witkin, B.R., Altschuld J.W. (1995). Planning and conducting needs assessments: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.