Technology and Business Schools1

James Fleck

Introduction

This paper considers how technology is currently affecting the Business School world, and seeks to draw out some of the implications and ramifications that Business School administrators and educationalists should bear in mind. The paper starts out by describing a particular approach to teaching pioneered by the Open University Business School, contrasting it with the more traditional approach generally found in the sector. Then, drawing on insights from analyses of technology development which employ a broad view of technology as including organisational and cultural aspects as well as the narrowly instrumental „hardware” aspects several important general observations are made: First, it should be recognised that the same technical elements can be used in different ways to realise a range of distinct business and learning models: there is no simple deterministic link between the technical elements and the approaches adopted. Second, it should be recognised that an unprecedented range of models are currently being explored, opening up vast opportunities for innovation, both in terms of approaches to teaching and achieving economic viability. And third, Business School administrators need to recognise fully that they have an important and very active part to play: they can, and should, actively „shape” technology, as otherwise by default they shall become victims of its impact.

The OU learning mModel

Most Business Schools employ minor variants of the traditional model of face-to-face, classroom-based teaching, in which an individual lectures to a large group of students. The main mode for teaching and learning is the transmission of knowledge by means of verbal communication, supplemented by texts. Some specifically technical elements, such as PowerPoint slides and videos, are used to support the teaching and learning, but these do not change its essential character.

A very different model was initiated by the UK's Open University, founded in the 1960s and widely recognized as one of the most important educational innovations of the late 20th century, with many imitations (some 50 or so now) around the world.

The original concept was for a „University of the air”, with lectures broadcast over television and students self studying with the aid of correspondence materials. The lectures were broadcast in the early hours of the morning after the normal entertainment schedule. Very early on, the need for careful design of the recorded materials due to the exigencies of TV production led to explicit consideration of the content and pedagogic processes. It also led to a different „rights” regime, where ownership of the intellectual property became invested in the institution rather than remaining solely with the lecturers as in the traditional mode of lecturing. There was also a commitment to making education accessible to all (the „openness” of the university) and this also forced attention to the design of effective pedagogic progression. The original intention was to draw upon the services of lecturers already employed in established institutions, and the University was headquartered in the new town of Milton Keynes, mid way between the university towns of Oxford and Cambridge and a similar distance from London with its high concentration of university establishments. But in the event, it became evident that there was a need for dedicated academics permanently based in the university and working together in „course teams” to design and deliver the courses and programmes. These course teams, rather than traditional academic departments, became the basic unit of identity in the Open University and this remains the case today. The University has grown from strength to strength and is now the largest university in the UK with more than 220,000 students. It also achieves the highest levels of student satisfaction, consistently coming in the first three places in the Government survey of all educational establishments in the UK. It also achieves many other endorsements of high quality. The Business School itself, for instance, has triple accreditation from the three major Business School accreditation agencies, AACSB, EQUIS and AMBA, along with only another 43 out of an estimated total of 12,000 Schools in the world.

Over the forty years of its existence the Open University has developed and consolidated a distinctive learning model which it terms „supported open learning”. This has three main components.

First, course materials are designed and developed by teams of academics, practitioners and technical specialists. The development process is highly structured and involves the identification of learning outcomes, critical commentary by external assessors, rigorous testing phases, and above all the careful choice of appropriate pedagogic approaches aimed at maximising the effectiveness of the learning experience of the participants. Appropriate learning events are carefully designed, selecting from a range of activities: texts, DVDs, web facilities, electronic conferencing, face-to face tutorials, day schools, four or five day residential schools, project work and different forms of assessment. This is an expensive process and typically might cost upwards of €3m for a completely new full year programme. In comparison, the cost of a conventional approach might amount to several hundred thousand Euros at most.

Second, tutorials and tutorial interactions are delivered at a designed student staff ratio of 16:1 for post graduate students and 20:1 for undergraduates, by specially trained tutors, or Associate Lecturers (ALs). These tutors do not present the materials or lecture, but rather they oversee student interaction, facilitate discussion and other activities and contribute insights from their own experience. This contextualizes the materials and course ideas, and generally enriches and „breathes life” into the course. In particular, in international settings, tutors are able to highlight international comparisons through interacting themselves with the basic course materials and contributing local illustrations and case studies. Overall this provides a „high touch” mode of interaction quite different from typical correspondence courses.

Third, the Open University and the Business School operate at massive scale, with many thousands of students around the world. A sophisticated, secure and robust IT and logistics infrastructure is consequently necessary, to manage the students and the tutors, ensure the accurate and timely distribution of materials (the OU is the largest user of the British Post Office), and to oversee the administration of student records and assessment. Consider, for example, the challenge of ensuring that examinations are carried out simultaneously across the 11 time zones in Russia!

These three components together essentially comprise the general OU teaching model, which is usually described as „supported open learning”. Within the Open University, the Business School has evolved a specific variant of the OU's model, one which is particularly appropriate for management and professional education. This is a practice-based approach, and it was pioneered by Charles Handy in the 1980s to develop the ideal of Schon's „reflective practitioner”. Handy was a lead contributor to the development of the Open University Business School's first course „The Effective Manager”. This course has gone on to impact and inspire many thousands of students around the world, including for example tens of thousands in Russia and Romania.

In this practice-based approach, there is a fourth, additional component to the model. The students themselves are explicitly designed into the courses as active elements of the course and the learning processes, not passive recipients of information or essentially accidental participants in casual interactions. The course ideas and assessments are carefully presented in such a fashion as to maximize the opportunities for students to apply immediately in their own working practice. Moreover, in the Business School, the tutors are drawn primarily from industry and commerce, and bring their own practical experience to bear. Given that a major target audience for the Open University Business School is working practitioners, the careful harnessing of the students' own experiences through project work ensures relevance and timeliness, and broadens the range of issues covered. Furthermore, experience shows that this approach provides considerable benefit for the employing organisation, as well as the studying individual. In a very real sense, the student's work colleagues are enrolled into the learning process.

The traditional learning model

The OU's model is very different from the traditional one and makes use of a rather different technology base, quite different working practices on the part of academics, a very different division of labour in the overall workforce and very different implicit contracts of employment (intellectual property rights reside with the Open University for course materials as compared with conventional custom and practice where individuals own their own lecture notes, for instance).

Most Business Schools still use variants of the traditional model of face-to-face, classroom-based teaching, conducted by an individual either lecturing to, or facilitating discussion among, a relatively large group of students. The main mode for teaching and learning is the transmission of knowledge by means of verbal communication, supplemented by texts. Sometimes, as with the case study method, there is arguably more reliance on the printed texts and students' own thinking rather than the pronouncements of the professor. Some specifically technical elements are used, but they are employed to support, enable and enhance the main mode, and do not therefore change its essential character: it is still primarily a transmission of knowledge from a lone professor to many students.

The respective „technology complexes” which make up the different learning models as a consequence are in marked contrast. To simplify:

Conventional campus-based face to face teaching:

- Main mode of teaching is transmission of information;

- Craft approach primarily through individual activity;

- Knowledge moves with the faculty;

- Technology supports the transmission of information from lecturer to students, but is not essential;

- The Business Model is „cottage industry”.

- Main mode is student centred learning;

- Academics contribute as part of a team to course design;

- Design and delivery of the learning experiences is carried out by course teams;

- Knowledge is embedded in the course rather than the faculty;

- Tutors support students on their learning journey;

- Technology is essential for underpinning the process in many different ways:

- Supports communication among tutors and students;

- Electronic conferencing enables student interaction and learning over distance;

- Computers enable assessment;

- Extensive computer systems support the management and monitoring of students and tutors.

- There is an elaborate division of labour with institutionalized products;

- Business Model is an Industrialized approach.

The broad definition of technology

At this point it is worth considering: What is technology? For a serious analysis of what developments in technology might mean for the future of Business Schools, it is important to clarify what is meant by the slippery term, technology. It can mean a wide variety of things to different people. For many, technology is primarily seen as the physical instrumentation that helps us to carry out our tasks. But a little reflection quickly brings to light a far broader range of characteristics. The question yields a wide range of typical responses, including for instance the following: global communications; work redundancies; knowledge; usability; improvement; problem solving; innovation; impact on society; the creation and/or removal of work; mobility; control; invention plus innovation; speed; the internet and connectivity; an enabler of efficiency; something that young people are better at using; and perhaps more intriguingly, „a post-modern term for poetry”, or „the shoe that enables nations to take bigger steps” (from a Chinese MBA student).

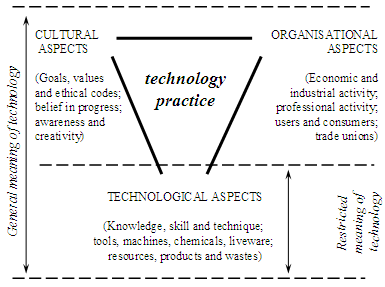

Quite clearly, therefore, technology is not a straightforward matter. Many analysts of technology development have addressed this challenge, coming up with a variety of specific suggestions. The strong general consensus is that technology is complex and multifaceted. Stewart Macdonald has opted for a broad catch-all characterisation of technology as „simply the way things are done”2. This is certainly worth thinking about, but is not so easy to apply in practice. In the context of analysing the deployment of technology in a range of cultural settings, Arnold Pacey proposed a broad, structured view of technology, seeing technology as a form of practice involving narrowly technical aspects, organisational aspects and wider societal aspects (see Figure 1)3.

Fleck and Howells have proposed a complex of factors to be considered in systematically working out how technology might be implemented in practice in specific contexts (see Figure 2)4. Different subsets of these factors prove to be relevant for different situations. The important point is that the successful implementation of a technology, even apparently quite simple ones, is likely to require a range of adjustments to an organisation far beyond the purely technical level and to require the employment of particular practices, techniques and skill sets to enable effective exploitation of the basic technical elements themselves.

|

PURPOSE MATERIALS ENERGY SOURCE ARTEFACTS / HARDWARE LAYOUT PROCEDURES (+ programs, software) KNOWLEDGE /SKILLS / QUALIFIED PEOPLE WORK ORGANISATION MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE COST / CAPITAL INDUSTRY STRUCTURE (suppliers, users, promoters) LOCATION SOCIAL RELATIONS CULTURE |

Some key observations about technology and the business School World

Analytically, it is possible to distinguish two broad sets of considerations bound up with the new technologies. On the one hand there are the implications for the structure of the business school sector as a whole, affecting issues of competition and the nature of the markets addressed. At root these considerations concern the basic nature of the business models for Business School operation in the developing global context. That is, how can economic sustainability be achieved and how do the available technologies affect the range of ways of doing this? On the other hand, there are the implications for the nature of the learning process itself, what might appropriately be termed the „learning models”. The first is primarily directed at the external context for business school operation, while the second involves the internal context, although of course the two are tightly inter-related.

Global business models

Technology, in the shape of both Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and transport technology, is a key element in globalisation. Together, they are shrinking the world and intensifying interaction between historically remote regions. Business Schools are responding in a variety of ways. Economically cheap, though perhaps environmentally expensive air travel is enabling the speedy movement of faculty and students, creating the „fly in a guru” syndrome, and fomenting the recent rapid growth of student exchanges. A range of means of distributing lectures electronically is being experimented with. For instance, at the Royal Institute of Technology in Kista, Stockholm, sophisticated electronic lecture theatres have been used for over ten years, linking classrooms in Stockholm, St Petersburg and the island of Gotland. This multiplies the effective class size and diversifies the location. Typically a lecturer will move around the three centres, being physically present at one while transmitting to the other two. This approach to „virtual presence” has been so effective that students cannot remember whether the lecturer was in fact present at a particular lecture in person or merely electronically when asked at the end of the course. The set up has also been used for intercontinental connections between Sweden and Stanford University in North America, and between Sweden and Chile in South America.

More radical means of distributing lectures and materials to individual recipients have also been explored using mobile phones and podcasting, thereby opening up a new arena of mobile learning. The iTunesU operated by Apple provides a massive selection of learning „albums”. The Open University contributes to iTunes U and over a period of 18 months since its inception, the OU experienced over 16 million downloads. This has provided a huge boost to reputation and presence, but since the service is free under the conditions that Apple imposes, it is not in itself economically sustainable; that is, it is not a viable business model in itself. Another OU project, OpenLearn, an Open Educational Resources (OER) initiative that provides 8,000 hours of free course ware over the Internet, has also attracted a huge volume of visitors, some ten million unique visitors over the two year life of the project so far. This was funded by a $10m grant from the Hewlett foundation, and many thousands of pages of materials are available over a VLE structured to provide learning support and to facilitate discussion among participants5. However, in this case 13,000 student registrations on fee paying courses have resulted, suggesting the basis for a viable business model with free entry services, and a revenue generating follow-through once people have been successfully attracted to the distinctive learning experience showcased in the free elements.

Such technology enabled developments are offering severe challenges and constraints as well as opportunities to the Business School world. The potential reach of any one School is very much increased. Through the internet, students can access materials and resources from anywhere in the world. At the same time this accessibility means that competition between Schools is much intensified. Schools are now less protected by their geographic location from competition with institutions located elsewhere, while local markets have the option of considering a wider range of Schools. Improvements in communications and accessibility also mean that quality (both high and low!) becomes more evident and can be more easily compared. Furthermore, the new ICTs are opening up new market segments. People in work can access educational materials from their place of work, while mobile professionals can maintain a significant sense of continuity despite travelling around the world. Together these trends are intensifying completion in vertical rather than spatial segments. Large Corporations are more aggressive users of ICT in the global context than educational institutions and are consequently a major driving force. Many major companies now make absolutely routine use of video conferencing whereas it still tends to be an awkward novelty for most Business Schools. EMC, the memory specialists, have for 10 years been using a portable classroom. A large chest is kitted out with 20 laptops, general communications equipment and whiteboard pens. This enables sales and service personnel, and even customers to attend remote classes anywhere in the world, presented from corporate headquarters outside Boston (the pens were found to be essential kit because, although most venues provided whiteboards, they rarely had working pens available!). Moreover, internationally operating corporations such as Rolls Royce, who commission education and training from Business Schools, are increasingly demanding that educational services are provided wherever in the world they are operating. Further, they want the educational services to be of demonstrable and equal quality wherever they are provided. These globalisation-related developments are enabling the emergence of a range of business models for Business School operation far beyond the traditional single geographical location, localised market and face to face delivery. Indeed, a recent European Foundation for Management Development (EFMD) paper identified some 11 distinct models for the global business school.

Technology enabled learning models

With respect to the more specific learning models afforded by the new technologies, it is very clear that the current period is one of intensive experimentation. The full scope of these new technologies has not yet been identified. The potential of the new technologies and, importantly, their combinations, are still being explored. Different „blends” of ICT; email; mobile phones; on-line; webcasts; video conferencing; electronic fora; texting; podcasting, not to forget variants of face to face teaching, are being entertained. No particular combinations have yet emerged as standard proven solutions for the learning model, although it is possible to identify a provisional set of relatively stable configurations as follows:

- Conventional: craft based „cottage industry” model. This is described above, with the main mode of learning firmly based on face-to-face lectures. Here there is a widespread base of use of technologies such as video lectures, PowerPoint presentations, Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs), and the internet. However, the use of these technologies does not alter the fundamental teaching model. Essentially they sustain and (perhaps) enhance the traditional teacher/lecture „cottage industry” mode of operation.

- Correspondence Distance Learning. This is a longstanding mode in which written texts are distributed to students who then self study, perhaps presenting themselves for test or examination. New technologies such as audio and video disks, and multimedia CDs or DVDs are increasingly supplementing or in some cases replacing printed texts. But again, these do not alter the basic learning model of distributed materials for self study, and hence again are used essentially to sustain the learning model, albeit in a more technologically sophisticated interactive form.

- Supported Open/Distance Learning is a form of blended learning in which distributed materials are complemented by more or less structured tutorial interactions with trained teachers. The UK Open University was the major pioneer of this approach and remains the leading exponent, with a range of variations including the practice-based approach employed by the Open University Business School. As described above, this learning model is characterised by the very careful and expensive development of the learning experiences and pertinent supporting materials, coupled with „high touch” teaching support.

- Distributed learning community: a group of participants who variably contribute to each other's learning on the basis of their own expertise through participation in some form of community. While such communities were traditionally found among professional and scientific groups, they have been given wider currency through the availability of a variety of so called „web 2.0” facilities and the advent of social networking sites such as Facebook and LinkedIn. Perhaps the most prominent current example is Wikipedia, although this does not have directed or structured learning as its primary objective. Nevertheless, there is experimentation in harnessing such communities for more structured educational purposes, in some cases using the methodology of action learning as a specific means.

- The „Freemium” model. This is an emerging learning model, and is an analogue of the voice over internet protocol adopted for the Skype telephone service. The essence of this model is the fostering of a massive user base of free provision of materials, together with the option of a relatively select range of value added services, the fees for which underwrite the overall operation. This is not yet a fully fledged learning model at least as far as it is independently sustainable in financial terms, but there are certainly several serious experiments proceeding at the present time. A notable example is the OU's OpenLearn project already briefly described above, and the term „Freemium” was coined to describe this and other similar projects at the Open University.

Issues: The eLearning Challenge

Many technical components such as PowerPoint, email, video lecturing, electronic conferencing, etc., have been employed in a sustaining manner6. But many commentators and practitioners believe that particular configurations of the basic technical components may yet produce an eLearning model that is radical and will ultimately prove to be disruptive. There is no doubt that eLearning can access different market segments; there is no doubt that the rate of technical development and improvement is extremely rapid; and there is increasing evidence and an increasing awareness that the educational experience provided through eLearning can in fact be as good as if not better than the traditional learning model. The overall consensus from studies comparing eLearning with traditional methods finds „no significant difference” in outcome7. Given that traditional pedagogy has been around for several thousand years, and eLearning for at most a couple of decades, this gives pause for thought. Further, eLearning has catalysed renewed attention to the process of teaching and learning, and has engaged a wide range of research with some 50 plus theories8. The new proposition that is offered by eLearning is the systematic harnessing of technology. It can be observed that eLearning is thereby facilitating a shift from traditional pedagogy to „pedagogics”, that is pedagogy with an explicit utilization of technology. Of course, there are many outstanding issues with eLearning: the unevenness of access to the web, the problematic nature of interactivity, navigational problems, the persistent preference for paper over electronic presentation, and how best to engage the social basis for learning in an electronic universe. For instance, it is interesting to consider the apparent „problem” of increasing plagiarism, which seems, at least in part, to be a product of the ease of electronic manipulation of text. Perhaps conventional academics are still trapped in the assumptions of the Gutenberg revolution, based on the essential „fixity” of text9. This fixity of text arguably underlies much current academic and teaching practice. Indeed, it underpins „author-ship” and „author-ity” of conventional academic products. Yet young people are growing up in an electronic-mediated modern world, in a new era that is characterised by an essential „fluidity” of text. In many cases (though admittedly not all!) they are genuinely puzzled by the debates over what is legitimate student work and consequently what constitutes plagiarism. Are current academic reactions a desperate attempt to retain the conventional basis of authority? Perhaps there is a need to move towards a concept of „collagist” or „originator” rather than the conventional „author”. And perhaps it is necessary to develop better ways of assessing deep understanding and knowledge than the conventional reproduction of text answers to standard essay or exam questions. This example shows clearly that educationalists cannot merely sit back and wait for the technicians to produce better technical elements. The challenge is to explore the ramifications of the technical elements and how they interact subtly with existing practices and institutions and open up new ways of doing things. The potential implications strike deep into the heart of what we do. If this challenge is not taken up, there looms the risk of being overtaken by those disruptive practitioners who are exploring and developing the possibilities even if they are not yet properly proven.

Conclusions: The role of administrators and educationalists

Administrators and educationalists in Business Schools are involved in a highly competitive enterprise. Therefore they must ensure that their Schools actively explore the immense potential and the wide ramifications of the new technologies coming on stream in the context of increasing globalisation. Moreover, they should not wait to adopt passively the technologies that become available. Bearing in mind the broad view of technology as a complex of technical elements, specific practices, techniques and skills and the appropriate organisational arrangements, they should address those elements within their direct purview and ability to control, and thus become technology makers rather than merely technology takers. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that technology, especially in the Business School world, is always just the means to an end, not the end in itself. Administrators and educationalists in the Business School world need therefore to be clear about what their purposes (ends) actually are. And this, surely, is to provide students with effective, relevant and above all, excellent learning experiences.

References

- C.M. Christensen, The Innovator's Dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail, Harvard business school Press, Cambridge MA 1997.

- J. Fleck, J. Howells, Technology, the technology complex and the paradox of technological determinism, „Technology Analysis and Strategic Management”, 2001, 13 (4) pp 523-531.

- R.A. Lanham, The Implications of Electronic Information for the Sociology of Knowledge [in:] Conference on Technology, Scholarship, and the Humanities: The Implications of Electronic Information, Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center of the National Academies of Sciences and Engineering Irvine, California 1992.

- S. McDonald, D. Lamberton, T. Mandeville (Eds), The Trouble with Technology - Explorations in the process of technological change, St Martin's Press, New York 1998.

- A. Pacey, The Culture of Technology, MIT Press Cambridge, MA 1983.

Dodaj do:

Facebook

Facebook

Wykop

Wykop

Twitter.com

Twitter.com

Digg.com

Digg.com

Spis treści artykułu

- Introduction

- The OU learning mModel

- The traditional learning model

- The broad definition of technology

- Some key observations about technology and the business School World

- Global business models

- Technology enabled learning models

- Issues: The eLearning Challenge

- Conclusions: The role of administrators and educationalists

- References

Informacje o autorze

Komentarze

Nie ma jeszcze komentarzy do tego artykułu.

Podobne zagadnienia

Lessons from connectionism in differentiating knowledge types

AMP: A tool for characterizing the pedagogical approaches of MOOCs

Using the Seven Futures framework for improving educational quality

MOOCs, Ethics and the Economics of Higher Education

Sometimes Shorter Is Better, But Not Always: A Case Study

Distance Learning: Classification of Approaches and Terms

What Can Traditional Colleges And Online For-profit Universities Learn From Each Other?

Przypisy

1 This paper is a restructuring, revision and update of an earlier paper: J. Fleck, Technology and the Business School World, „Journal of Management Development” 2008, 27 (4), pp 415-424.

2 S. McDonald, D. Lamberton, T. Mandeville (Eds), The Trouble with Technology - Explorations in the process of technological change, St Martin's Press, New York 1998.

3 A. Pacey, The Culture of Technology, MIT Press Cambridge, MA 1983.

4 J. Fleck, J. Howells, Technology, the technology complex and the paradox of technological determinism, „Technology Analysis and Strategic Management”, 2001, 13 (4) pp 523-531.

5 See openlearn.open.ac.u....

6 C.M. Christensen, The Innovator's Dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail, Harvard business school Press, Cambridge MA 1997.

7 See, for an ongoing review of such studies: www.nosignificantdi....

8 See for instance, tip.psychology.org.

9 R.A. Lanham, The Implications of Electronic Information for the Sociology of Knowledge [in:] Conference on Technology, Scholarship, and the Humanities: The Implications of Electronic Information, Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center of the National Academies of Sciences and Engineering Irvine, California 1992.

JAMES FLECK

JAMES FLECK